Mystery Behind High Lebanese Olive Oil Prices Solved

The Lebanese olive oil industry is facing another threat: cheap imports are flooding the market.

Lebanon’s olive oil industry is suffering due to lack of government support, leading to an influx of cheaper imported olive oil and causing local farmers to struggle. The government’s absence in protecting the agriculture sector has resulted in a surplus of olive oil, with merchants profiting by selling cheaper, imported products as Lebanese olive oil.

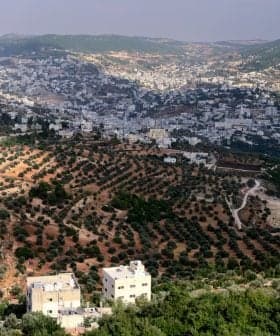

Lebanon is blessed with beautiful and fruitful land and a mild climate that is perfect for growing olives and many other crops that help the nation’s economy flourish.

However, these natural factors are not enough for the agriculture industry to flourish on its own and offer its workers a decent living: in addition to favorable natural conditions, the agriculture industry needs financial support from the government in order to survive and thrive. Unfortunately, the support that the Lebanese olive oil industry needs from the government has not been given, and it is consequently suffering severely.

The government is totally absent when it comes to the agriculture sector and namely olive oil.

According to Adel Oewis, an olive oil farmer and the head of the co-op in Zgharta, “The government is totally absent when it comes to the agriculture sector and namely olive oil… Lebanon is flooded with olive oil imported at a cheaper price from other countries. What we want from the government is to protect our production and also to secure export markets for the oil we produce.”

Lebanese farmers have asked the government to protect the local agriculture industry by stopping or restricting the importing of items such as olive oil that are produced locally. The head of the Lebanese Farmers’ Association, Antoine Howayek, expressed similar sentiments to Oewis, saying that, “We should put an end to the smuggling taking place from Syria and other countries in a bid to protect the sector.”

The lack of protection has been harmful to both the agriculture industry and farmers themselves: in some parts of Lebanon such as Kfeir, farmers rely solely on the production of olives and olive oil for a living, and smuggling has caused approximately 80 percent of the people in such areas to immigrate elsewhere.

Howayek also provided startling statistics: there are 59,000 hectares of land in Lebanon producing around 75,000 tons of olives, and “If we consider that 50,000 tons of olives go to the production of oil then we should be having over 10,000 tons of yearly olive oil locally produced,” he said.

However, of the nearly 10,000 tons of olive oil that were exported in 2016, many were not actually Lebanese olive oil. Many merchants are not exporting locally produced olive oil, they are in fact buying smuggled products from Syria and Tunisia at cheaper prices to export it to other countries, and there is no system to prevent this or confirm that the exports are in fact Lebanese olive oil.

Consequently, Lebanese farmers are stuck with a surplus of olive oil at the end of their harvest, and merchants end up maximizing their profits by selling cheaper products at higher prices.

Blominvest Bank studied the challenges facing the Lebanese olive oil industry, saying that, “Lebanon’s high cost of olive production has negative consequences for its competitiveness in the domestic and international markets. To compensate for this constraint, Lebanon imports inexpensive oil from other Mediterranean olive oil producing countries, where the cost of production is much lower. Such imports profit bottlers, who mix lower-priced imported oil with Lebanese oil to reduce costs and sell into both domestic and international markets,” it said.

“Lebanon does not impose any traceability or labeling requirements with regards to origin, making it easier to blend oil imported from abroad that may be lower in quality,” Blominvest found, ultimately concluding that, “The government should give financial support since turning a traditional mill into an automated one can constitute a hefty investment depending on the capacity and sophistication.”