'Heroic' Olive Cultivation in Italy Still a Struggle, but Fighting Back

Responsible for some of Italy's most characteristic olive oils and landscapes, moves are afoot to promote awareness of the country's heroic olive cultivation.

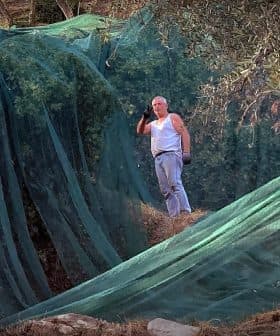

Olive grove in the Sicilian countryside

Olive grove in the Sicilian countrysideTwo recent initiatives in Italy have focused on highlighting the challenges faced by olive growers in difficult terrain, with a recent conference in Tuscany following a census launched by the Ministry of Agriculture. Producers are working to create a sustainable future for this type of agriculture, recognizing its importance in producing characteristic products and protecting traditional landscapes.

Two recent initiatives in Italy have attempted to shine a light on the difficulties faced by those who practice olive growing in challenging terrain. A recent conference in Tuscany, which bought together producers and experts, followed the launch of a census in January by the Ministry of Agriculture with the aim of mapping out for the first time what has been referred to as the country’s “heroic cultivation.”

We’re not dealing with a purely agricultural problem, but one that affects everyone.

There are also signs of producers fighting back to create an economically sustainable future in some parts of Italy. It is a recognition that this type of agriculture is not only behind some of the country’s most characteristic products but frequently plays a vital but unheralded role in protecting traditional landscapes.

The term “heroic cultivation” was coined to describe the punishing nature of agriculture that is carried out in areas where the land is too steep, or too remote, for mechanical assistance.

Examples frequently cited include farmers growing the prized lemons on the steep terraced land around the Amalfi coast, and the efforts involved in growing grapes on the island of Pantelleria, which have to be transported by boat to Sicily for processing. Three years ago, we also highlighted the difficulties encountered by Massimiliano Gaiatto, who makes oil from olives that he grows on the hills surrounding Lake Como.

One man acutely aware of the challenges that farmers face is Giampiero Cresti, vice president of Toscano IGP, the consortium that protects standards of extra virgin olive oil produced in Tuscany, a region where around 30 percent of olive cultivation is undertaken on land too steep for conventional farming methods. In April, Toscano IGP organized a conference bringing together producers and agricultural experts to discuss the value of this type of farming and approaches to promoting and safeguarding it.

“The principal difficulty,” Cresti told the Olive Oil Times, “is the impossibility of using machinery or technology in the olive groves — everything has to be done manually with tools that are often old and no longer effective.”

The “very real risk,” Cresti added, is the abandonment of this land due to a lack of labor and scant economic return. When this happens, olive oil production is not the only thing to suffer.

The abandonment of the centuries-old agricultural systems of water management, for example, could lead to an increased risk of landslides, while the dry-stone walls dotted throughout the Tuscan landscape could also disappear. “In short,” cautioned Cresti, “we’re not dealing with a purely agricultural problem, but one that affects everyone.”

In recognition of the risks Cresti described, the Italian Ministry of Agriculture launched a census in January aimed at mapping out the extent of Italy’s heroic agriculture for the first time.

Any agricultural business, including olive farmers, that considered itself to be farming in terrain presenting particular difficulties was invited to participate. The then Minister for Agriculture Maurizio Martina, speaking to La Stampa newspaper, said that the survey “would make it possible to work on ways to support these heroic enterprises,” adding that they were “one of the most characteristic forms of Italian agriculture.”

Further north in Liguria, farmers face similar challenges to their counterparts in Tuscany but are uniting behind a project that aims to make olive cultivation on the region’s steep slopes an economically sustainable practice, without support from the government.

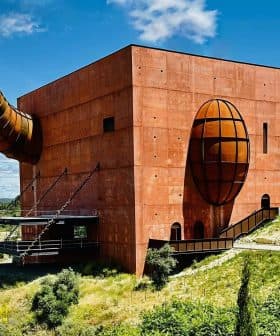

TreeDream was set up by Flavio Lenardon, originally from Friuli Venezia Giulia but Ligurian by adoption. He was struck by what he calls the “cathedral” of Liguria’s terraced slopes that rise steeply from the sea and are sustained by miles and miles of dry-stone walls, with the small plots in between home to many thousands of olive trees. “A shiver ran through me,” said Lenardon. “When I saw that most of these marvelous walls were in a state of abandonment, with the woods taking over, I realized that we were losing our history and our roots.”

Lenardon defines TreeDream, which has a tree held in an outstretched hand as its logo, as a “cultural movement.” The project unites olive farmers and others with an interest in preserving the region’s agricultural landscape. “Its aim is the rebirth of olive cultivation at altitude and communicating the challenges linked to this kind of land, bringing together all those who do not want to abandon what their ancestors built,” said Lenardon.

The consequences of the project go beyond an increase in the quantity of olives produced at altitude and could play an important role in protecting villages from natural disasters. In 2011, flooding and landslides hit villages in Cinque Terre causing widespread damage. The disrepair of the area’s dry-stone walls and terracing was widely believed to be one of the contributing factors.

Lenardon believes the key to a return to traditional olive cultivation in Liguria is an awareness of the special qualities of oils made from olives grown at altitude. “It is well-known by now that the presence of aromatic and health-giving components is increased by situations of water and climatic stress, such as those you find in areas of higher altitude,” he said. It’s a view supported by others, including experts such as writer and journalist Luigi Caricato who dedicated a guide to high-altitude olive oils in 2005.

Unique oils from olives harvested by hand in challenging conditions should command higher prices but communicating that to consumers is not always easy. To help farmers who are part of the TreeDream project, Lenardon came up with a label, which he called Taggialto. The name combines Taggiasca, the most widespread olive cultivar in Liguria, with alto, Italian for ‘high.’ Olives from farms in the scheme are milled and bottled under the label and it has enjoyed success, winning a listing at the famous Milanese food hall, Peck.

Lenardon was clear on what is required to safeguard Liguria’s heroic olive cultivation and, in turn, the preservation of its rural geography and culture. “All that producers need is for their product to be recognized for its real value. Support from institutions should focus on communication, helping our movement and others relaunch this type of olive cultivation,” he said.

There are also encouraging signs elsewhere in Italy. Olive Oil Times recently reported on the growth of olive cultivation and production of olive oil in Valle d’Aosta, the smallest and one of the most mountainous regions of Italy.

At the other end of the country a new project, with the name Regeroli, was announced in May in the southern region of Calabria with the aim of relaunching olive cultivation at altitude in the region’s Sila mountain range.