6.9K reads

6.9K readsBusiness

Celebrating South America's Historic Olive Trees

Sudoliva is a group working to document and preserve centuries-old olive trees in the Americas, with a focus on promoting a continental olive oil culture. The organization holds a heritage olive tree contest to recognize and protect these significant trees, with winners including the Savona Heritage olive tree in Chile and the Tláhuac Heritage olive tree in Mexico City.

While the olive tree is widely associated with the Mediterranean basin, it also has deep roots in the Americas.

The first olive trees arrived on the continents with Spanish missionaries, establishing a foothold in many former colonies, from Argentina to California.

However, the history of these centuries-old olive trees in South America has been largely forgotten with an estimated 70 percent of them having been removed to plant other crops.

See Also:Centuries-Old Groves Restored and Harvested at Trajan’s Historic HomeSudoliva, an organization dedicated to documenting and preserving centenarian trees in the Americas and promoting a continental olive oil culture, is working to change this at the second edition of its heritage olive tree contest.

Founder Gianfranco Vargas told Olive Oil Times that the event is an academic and cultural initiative created in 2017 that seeks to preserve healthy centenarian trees in the olive-growing regions of the Americas.

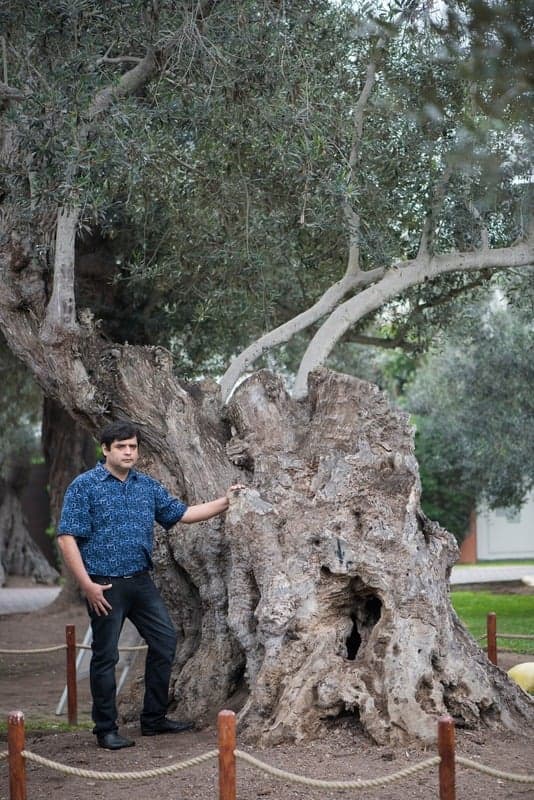

Gianfranco Vargas with the centenarian tree planted by San Martin de Porres in Lima, Peru (Photo: Eliete Vera)

Trees are nominated for the competition and assessed by a panel of judges based on their size, health and age, which is determined using historical documents and the non-invasive Santander Method.

Santander Method

Developed by the president of Santander Bank, who is an avid millenary olive tree collector, the Santander Method is a non-invasive procedure to estimate olive tree age. The method uses lasers to measure the radii and diameters of the olive tree from various points and uses this data to estimate for how long the tree has been growing.

However, Vargas said the most important criterion is the cultural and historical significance of the centenarian olive tree in the region.

The big winner from this year’s contest was the Savona Heritage olive tree located in the Azapa Valley of northern Chile. Based on historical data, “it was probably planted more than 450 years ago and is considered one of the oldest olive trees in South America,” Vargas said.

Indeed, historical documents show the tree was planted in 1550, a decade before it was thought olive trees arrived in South America.

“Having this data, it is possible that olive trees were planted in the region at that time, preceding what history tells of the entry of the olive tree to Peru, Chile and Argentina,” he said.

The competition also recognized an olive tree planted in Mexico City that is thought to be one of the oldest in the Americas.

Jorge Lombardi Arata with the Savona Heritage olive tree in Chile’s Azapa Valley (Photo: Eliete Vera)

“According to historical documents, [the Tláhuac Heritage olive tree] was probably planted by missionary Martín de Valencia and may be one of the first olive trees planted on the American continent, at almost 500 years old,” Vargas said.

Based on his research, Vargas said olive trees were brought to the New World for religious reasons by Spanish missionaries.

As a result, centenarian trees can be found across the continent at the site of historic missions, including in the rainforest of eastern Peru and the mountains of Colombia.

“Many archives of religious orders indicate requests for olive oil with urgency because the holiest sacrament for Catholics is a lamp of the tabernacle, which represents the presence of God,” Vargas said.

“The churches said, ‘we need olive oil; we need to plant olive trees; we need this product because otherwise we do not have the presence of God,’” he added.

Commercial olive cultivation began later in southern Peru and northern Chile, where the trees thrived in the climate and soil. Known as Botija olives in Peru and Azapa olives in Chile, the fruit was harvested when mature and became an integral part of the local food culture.

See Also:Making Award-Winning Olive Oil from California’s Centenarian TreesAccording to Vargas, South America’s centenarian trees also tell the story of the inequality that plagued the continent.

Since the first trees were brought for religious purposes, the Spanish crown prohibited indigenous people and, later, enslaved Africans from tending to them. However, this changed with the commercialization of trees.

For this purpose, Sudoliva recognized the Don Eulogio Baltazar Chanes Heritage olive tree, also located in Azapa, to prevent the region’s legacy of inequality from being forgotten.

“The Don Eulogio Baltazar Chanes Heritage olive tree from Azapa was also recognized, where there was a very important hacienda initially worked by native or indigenous slaves and later worked by slaves of African descents,” Vargas said.

“The idea is that we keep this history alive,” he added. “Our next objective after the contest is to make rules or laws in their favor.”

Sudoliva judges measure trees and use historical documents to confirm their age. (Photo: Eliete Vera)

Since 2017, Sudoliva has cataloged 51 centenarian trees in the Americas and has worked with governments in Argentina, Chile, Mexico and Peru on legislation to protect the trees.

“In Peru, we already have the first law from the previous contest that protects the centuries-old olive trees in the Moquegua region,” Vargas said.

“In Chile, based on this contest, we have already had contact last week with lawmakers from the Arica region to make a law to protect the olive trees of the Azapa Valley,” he added.

Sudoliva is also working with governments in Mexico and Argentina to protect centenarian trees in both countries.

Another prong of Sudoliva’s strategy is to help farmers and other locals who care for the centenarian trees develop gastronomic and cultural tourism around the trees.

Since many trees were removed for economic reasons, it stands to reason that creating economic value is one way to ensure their protection.

“We want it to be a ‘centenary olive tree route,’ he said. “That is the work being done so that this tree route is ultimately linked to two aspects, the religious aspect and the gastronomic aspect, with the gastronomic aspect based on each country’s regional cuisine.”