Making Award-Winning Olive Oil from California’s Centenarian Trees

In the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, Guilio Zavolta and Rachelle Bross seek to promote and protect the state’s historic olive trees.

Guilio Zavolta and Rachelle Bross

Guilio Zavolta and Rachelle Bross Olivaia’s OLA, located near Sequoia National Park, aims to preserve California’s olive-growing heritage by producing traditionally made extra virgin olive oil from hand-harvested olives. Co-owners Guilio Zavolta and Rachelle Bross rehabilitated neglected centenarian olive trees to create award-winning olive oils, highlighting the historical, cultural, and culinary value of California’s olive groves. Zavolta emphasizes the need to appreciate and promote high-quality extra virgin olive oil to sustain small-to-medium-size producers and elevate the product beyond being viewed as a commodity.

At the foot of the Sierra Nevada near Sequoia National Park, the producers behind Olivaia’s OLA seek to protect California’s olive-growing heritage and bring new appreciation to traditionally produced extra virgin olive oil.

“OLA is short for original Lindsay artisanal,” co-owner Guilio Zavolta told Olive Oil Times. “All our olives are hand-harvested and immediately milled to maintain the utmost freshness. Our artisanal approach, regenerative farming and attention to detail all work to make the most of the incredible fruit our trees produce.”

We have already lost roughly 70 percent of our (centenary) California olives. I hope our story… will help save what is currently in the ground.

Zavolta and his wife, Rachelle Bross, were introduced to Tulare County, where Lindsay is the fifth-largest city, and olive farming by Albert Vera more than 20 years ago.

“Knowing our appreciation for olives both because of my family’s history with olives in Italy and Rachelle’s interest as a nutrition expert in healthy food, Albert and his wonderfully warm wife Ursula continuously encouraged us to get involved not only with their olives but with olives in general despite being recent immigrants to California,” he said.

See Also:Producer ProfilesAt first, the decision to start olive farming was a distant goal. Going to graduate school – Zavolta has a Master’s degree in architecture, and Rachelle a Ph.D. in nutrition – and starting a young family took priority. Zavolta and Bross decided to wait to get involved in olive farming.

“We deferred getting involved until we were on more solid footings,” Zavolta said. “Unfortunately, several years later, both Albert and Ursula passed away suddenly, and the only way to celebrate what they had come to mean to us was to get involved with olives.”

With olive groves in mind, the couple searched for the right property in the olive-growing region near Lindsay.

“We pulled together whatever retirement funds we had been able to set aside, secured a loan and decided to start looking for olives,” Zavolta said. “After about a year of searching and as fate would have it, we became neighbors to Albert’s and Ursula’s estate.”

While many olive farms in California are grown at high-density or super-high-density, Zavolta purchased a property with neglected centenarian olive trees and now works to protect this increasingly rare type of cultivation in the state.

“While we were thrilled to become neighbors, we essentially bought a block of centennial trees that were in horrible shape and slated to be removed to make room for a more lucrative crop,” he said.

Although Lindsay was once a focal point of olive growing, conditions shifted. Pulling out mature trees to replace them with citrus or almonds had become more commonplace than rehabilitating historic groves.

Traditional olive acreage is typically planted for hand-harvesting, with 60 to 80 trees per acre (150 to 200 trees per hectare). However, modern acreage promotes mechanical harvesting, with 200 to 250 trees per acre (500 to 620 trees per hectare).

While the modern approach costs less and is more economically viable, especially in California, Zavolta and Bross decided to rehabilitate mature olive trees rather than pulling them out and replanting them.

“Determined to honor our ‘olive’ friends and as immigrants to California who had just learned of the rich heritage of the Lindsay area, we set out to rehabilitate our trees so that we could establish some level of cashflow by selling our olives to one of the two remaining processors in California,” Zavolta said.

The process was not smooth. Zavolta and Bross navigated many twists and turns as they investigated their options.

“During the process and after years of rehabilitation, we discovered that we had many unique olives that could not be sold to the processor,” Zavolta said.

“Eager to make the most of what we had gotten ourselves into, we decided to make some oil for ourselves,” he added. “We were amazed at the wonderful, unique and fruit-forward nature of the oil and immediately thought of our dear friends and whether this was one of the many gifts from above that would come our way.”

After five years of producing olive oil on a small scale, Zavolata decided to make a commercial batch, naming it Bloc X Blend.

“The name arose as ’X’ because we had no idea what these unique olives were, and ‘Blend’ because it was a field blend,” he said with a smile.

Block X is an olive grove over 100 years old and contains more than nine varieties, including Manzanillo, Mission and Sevillano. Many of these cultivars include unique rootstock and, according to Zavolta, yield distinctive-flavored olive oils.

After the first harvest, Zavolta said the oil was recognized at several local competitions. “Not only were we thrilled about the awards, but we felt that the value we saw in our trees was validated,” he said.

Winning awards reaffirmed the benefits of saving the ancient trees, highlighting their historical value, as well as their cultural and culinary value.

“Aside from the value the trees had because of how we got started, we felt the trees had proven their value as the source of a unique oil, as the conveyor of the region’s rich heritage and as a cultural landmark,” Zavolta said.

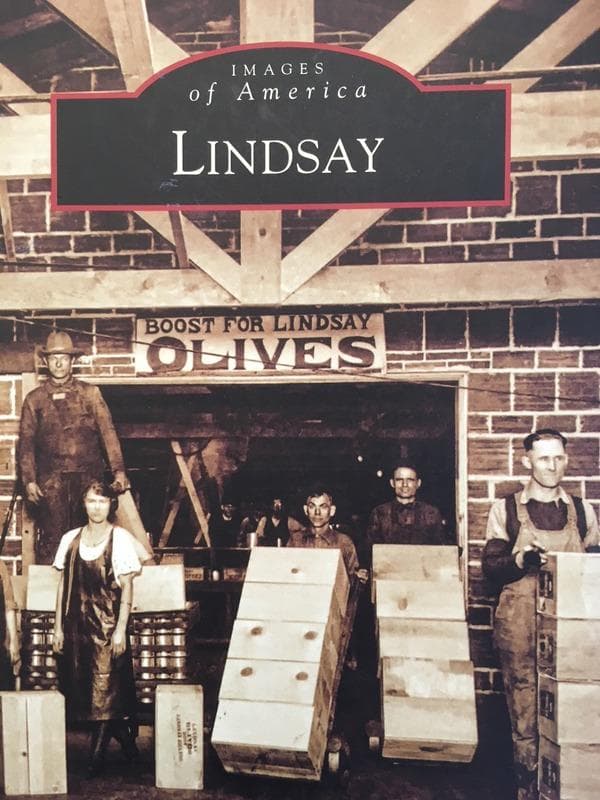

“We, of course, wrapped our bottles and tins with images of our majestic trees and an image provided by the Lindsay Museum of the original Lindsay plant that at one time employed over 500 people,” he added.

The original Lindsay olive plant employed more than 500 people at its peak.

With Olivaia’s OLA, Zavolta hopes that California’s history of growing olives will find a new vitality.

“We are proud to be putting ‘history in a bottle’ for all to enjoy and appreciate, and we hope that from now on, the perception of value goes beyond the simple bottom line and is understood holistically and sustainably,” Zavolta said.

“We have already lost roughly 70 percent of our original California olives,” he added. “I hope our story, together with the continued efforts by the industry leaders, will help save what is currently in the ground.”

His centennial trees have continued to garner awards. Zavolta said the older trees have deep root systems and can draw water in ways newer plants cannot. The rewards of legacy olive trees are further enhanced with artisanal care and regenerative farming practices Olivaia uses.

Earlier this year, the company earned three Gold Awards at the 2023 NYIOOC World Olive Oil Competition for a Sevillano monovarietal, a blend and an extra virgin olive oil made from a wild variety.

“Winning helps you know that you are doing something right. It also allows you to claim that there is something special about your extra virgin olive oil,” Zavolta said.

“The NYIOOC has built the voice and credibility. It provides producers like Olivaia’s OLA the tools to market their prized extra virgin olive oils,” he added.

Along with its acclaimed extra virgin olive oils, Zavolta said the company will also launch a brand of artisanal table olives, focussed on quality and displaying the organoleptic features of the fruit of its centenary trees.

“From the beginning, we set out to redefine the notion of value in trees like ours; we believe our extra virgin olive oil and our story help redefine value,” he said. “We hope to do it again with the upcoming launch of our own cured artisanal table olives.”

The launch comes in the aftermath of what Zavolta described as a poor harvest for his part of California.

Olvaia OLA earned three Gold Awards at the 2023 NYIOOC for olive oils sourced from centenary trees.

“2023 is somewhat devastating since after years of drought and low crops, the expectation was to have a great year to recuperate from the previous years, and that does not look to be the case,” he said.

“At least for our region, the crop is low enough that we will not even be able to cover our farming costs,” Zavolta added. “This, together with rising labor costs, is a combination that may prove to be lethal to more growers despite the ‘value’ argument.”

“The profit margins for growers are so low that it does not take much to put them in an upside down situation,” he continued. “I think it is time as a nation to start appreciating this, or we may continue to lose more and more growers to corporate farming.”

Promoting extra virgin olive oil is an ongoing challenge. Zavolta said that producing award-winning olive oil requires proper care, storage, marketing and sales timing so consumers can truly taste the difference and experience extra virgin olive oil’s health benefits.

“We need to do everything we can to sustain the small-to-medium-size producers,” Zavolta said. “We need a bit of everything on the market, but right now, it is tough for the great extra virgin olive oils to get onto grocery store shelves. The reality is that folks need to be exposed to great extra virgin olive oils to want great extra virgin olive oils.”

He believes producers must work more closely with retailers to promote extra virgin olive oil in cooking and explain what it takes to achieve award-winning quality.

“The culinary delight that comes with it, the health attributes that are associated with it, and the potential connection to a local grower or producer are all values that could justify the higher cost of a great extra virgin olive oil, and the message needs to be disseminated,” Zavolta said.

For Zavolta, extra virgin olive oil must follow in the footsteps of wine. “We need to stop thinking of extra virgin olive oil as a commodity,” he said. “It may be so for some, but it should not be for all.”

Share this article