Brazilian Guidebook Profiles Local Producers

The second edition of a guide to Brazilian olive oils tells stories of the people behind the products.

Sandro Marques

Sandro MarquesSandro Marques has released an updated version of his Brazilian olive oil guidebook in English, focusing on telling the stories of the olive oil producers in Brazil and their ties to their European ancestors. Marques spoke to 45 producers to create the guidebook, aiming to help consumers understand the production process and the people behind the olive oil.

After his first edition was well received, Sandro Marques has published an updated version of his Brazilian olive oil guidebook with an edition in English.

Recurring in all these stories are people wanting to recover an ancient tie they have with their grandparents that came from Europe.

“The main difference this year is that I really get to tell the stories,” Marques, a member of the Organizzazione Nazionale Assaggiatori Olio D’Oliva and editor of Um Litro de Azeite, told Olive Oil Times. “People will look at the olive oil and will know who produced it, how he or she started producing and why the olive oil is important for them.”

Marques wanted to expand upon the collection of stories he started hearing when he began researching for the first edition of the book in 2016. Back then, his main goal was to create a written record of olive oil producers who were in Brazil.

“I noticed that our Brazilian production was more or less consolidated, but it was difficult to find producers, where they were and I was very curious about their stories,” he said. “So by the end of 2016, I decided, since there was no data, that I was going to go out and get the data.”

See Also:Award-winning olive oils from Brazil

Marques spoke to about 45 producers for the guidebook, all of whom are producing olive oil on a commercial level.

“There are of course many more producers in Brazil, but my criteria is a producer that already has a commercial brand with a label,” he said. “I want to help on the consumer end. I want consumers to know what good oil is and how it is produced as well as who are the people who produce it.”

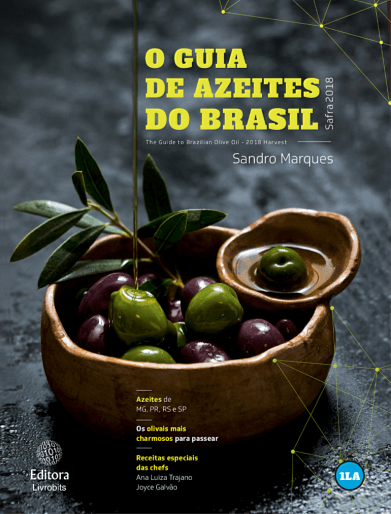

Guide to Brazilian Olive Oil / Sandro Marques

Marques began by contacting olive oil producer associations. However, many producers in Brazil are not associated with these groups, so he combined new and old methods of communication to find the rest: the phone book and social media platforms.

“It was really what we call in Portuguese a ‘small ant job,’ because we did it little by little until we finally had all the data,” he said.

Once all the producers were contacted, he had them send their samples to his office in São Paulo where he tasted them and wrote his observations. He also included a paragraph about the producer.

In his latest edition, Marques was able to go back and really talk to all of the producers to find out more of their stories.

“I wanted to tell the story of Brazilian olive oil producers. About their lands and about the context in which they are producing,” he said. “There’s always a component of passion that strikes, even if the producer starts for commercial reasons.”

He recounted one of the stories that stuck in his mind the most. It was told to him by Joice Capoani, the granddaughter of Jandir, the latter of whom dreamed of his grandmother’s Italian olive groves for his entire life before finally planting his own, well into his retirement years.

“Cheerful as a young boy, Jandir Capoani strolls around the grove with his granddaughters,” Marques writes in the book. “The trees help remind him of stories of his ancestors from Lombardy, who established themselves in Bento Gonçalves at the beginning of the twentieth century.”

“Jandir founded a factory, lived his whole life as an entrepreneur in the industrial segment and it took him almost 80 years to rescue the origins and passion for olives that lived in his memories… [Now] his granddaughters are taking an interest in the business, and the olive oil extracted this year makes a bridge between Jandir’s ancestors and Olivia, his great-granddaughter, who will see this story written in the leaves of the trees of Fazenda Tarumã da Boa Vista.”

Marques said this theme of returning to a previous and ancestral way of life was common among many of the producers with whom he spoke for the book.

“Since we’re a country composed of immigrants, what is very recurring in all these stories [are] people wanting to recover an ancient tie they have with their grandparents that came from Europe,” he said. “They try to honor their ancestors by cultivating olive trees in Brazil. Almost every story has that component.”

In spite of just having finished this year’s edition, Marques is already thinking ahead to next year. He plans to expand the guide to include Brazilian oleotourism ventures, that are slowly springing up around the country.

“There were very few last year, there are quite a few this year and I already know there are people doing huge things for next year,” he said.