Decoding the Olive Fly's Symbiotic Secret

The olive fruit fly is a major pest in the Mediterranean region, causing significant damage to olive crops and resulting in annual losses of nearly €3 billion, primarily through the feeding of its larvae on olive fruit. Recent research has focused on the symbiotic relationship between the olive fruit fly and Candidatus Erwinia dacicola, with genetic studies revealing different haplotypes across various populations and suggesting potential region-specific approaches for pest management based on this deeper understanding.

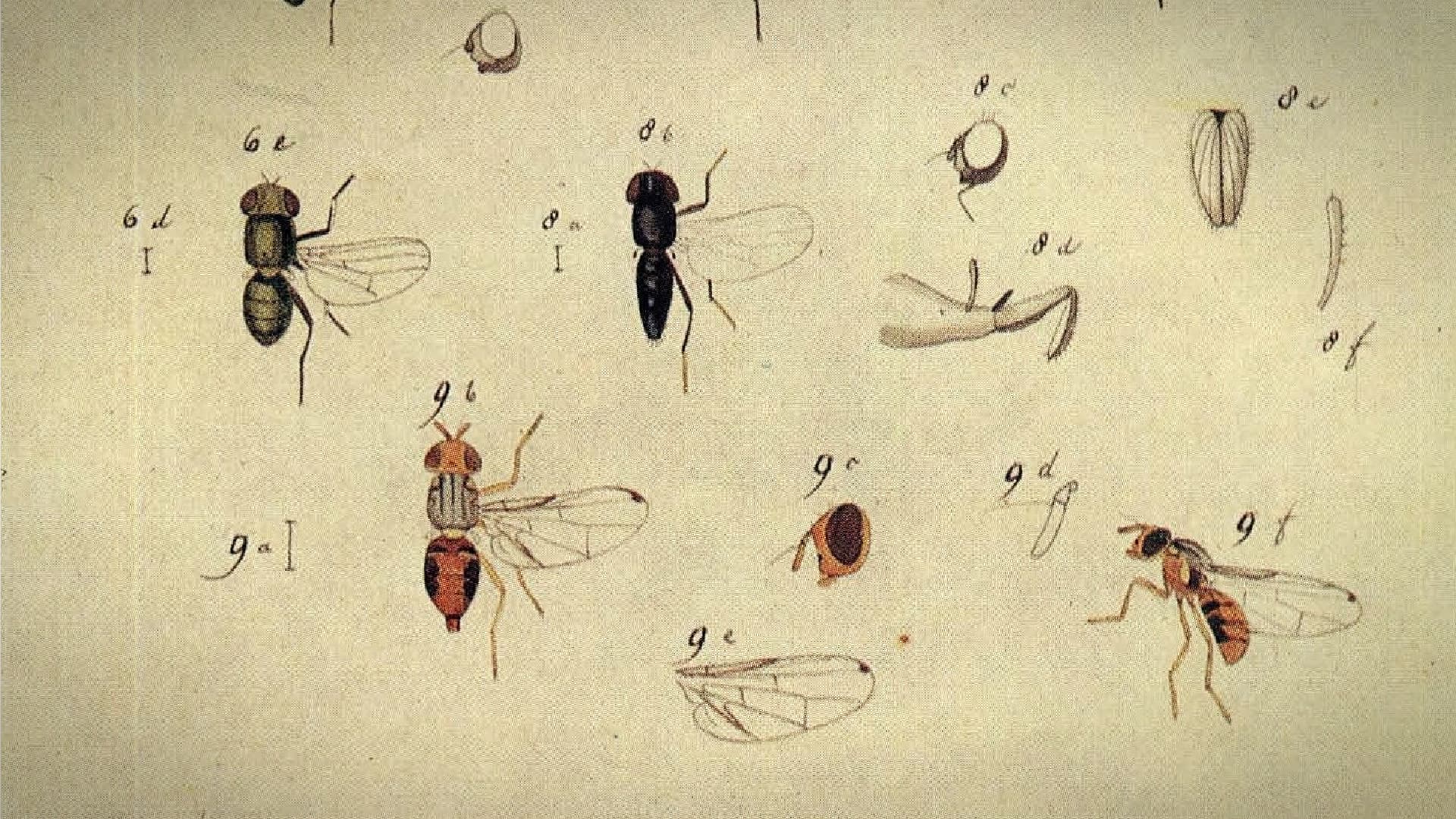

The olive fruit fly (Bactrocera oleae) is the most significant olive grove pest in the Mediterranean region and worldwide.

The damage is caused by its larvae, which feed on the olive fruit, causing significant quantitative and qualitative losses in fruit and oil.

Each year, the pest accounts for more than 30 percent of the destruction of all Mediterranean olive crops, which equates to annual losses of almost €3 billion.

See Also:Study Suggests Stink Bug Caused Mysterious Fruit Drop in ItalyInsecticides have long been the primary recourse against olive fruit fly infestation, as in the case of many other olive pests, such as the olive moth.

Environmental impacts, such as toxicity to non-target organisms, aquatic pollution and human food chain contamination, have resulted in the recent withdrawal of an unprecedented number of insecticide components via the implementation of European Union regulations.

In addition, the widespread use of pesticides combined with the pest organisms’ brief life cycles has resulted in resistant strains.

Unlike most other pests, however, the olive fruit fly almost entirely relies upon a symbiotic bacterium, namely Candidatus Erwinia dacicola.

The insect larvae require this symbiont to feed upon immature green olives by overcoming the olive’s natural chemical defenses, such as oleuropein, and is an important factor in larval development when feeding upon black olives.

It also increases egg production in adult females under stressful conditions.

Because of this unique relationship between insect and bacterium, Ca. E. dacicola has been the subject of recent research into novel control methods.

(Photo: Alvesgaspar)

It has been shown, for example, that certain antimicrobial compounds, such as copper oxychloride and viridiol, can interfere with the symbiotic relationship, leading to disrupted larval development and decreased hardiness in adults.

New research published in Nature seeks to provide a more comprehensive knowledge base on which to build by carrying out the most detailed genetic study into the olive fruit fly and its symbiont.

The study examined both organisms’ bio-geographic patterns and genetic diversity across 54 populations spanning the Mediterranean, Africa, Asia and the Americas.

The researchers identified three primary bacterial haplotypes: htA, htB and htP.

Haplotypes htA and htB dominated the Mediterranean region, with htA prevalent in western populations (e.g., Algeria, Morocco and the Iberian peninsula) and htB in eastern areas (e.g., Israel, Turkey and Cyprus).

See Also:Low-Cost Olive Pest Control Solution in DevelopmentCentral Mediterranean populations exhibited a mixture of these haplotypes, reflecting a confluence zone influenced by the migration and selection of olive cultivars.

Archaeological evidence suggests that olives were domesticated in the eastern Mediterranean and spread westward. The researchers note that the genetic patterns of the olive fly and its symbiont align with these movements, indicating that human selection of olive cultivars likely influenced the distribution and adaptation of the pest and its symbiont.

For example, the genetic admixture of the central Mediterranean populations is consistent with the blending of eastern and western olive lineages.

Haplotype htP, unique to Pakistan, likewise highlights ancient geographic separation and evolutionary divergence, with the symbiont’s lower genetic diversity than the host fly suggesting a long-term association characterized by selective pressures.

South African populations were similarly distinct, reflecting the fly’s and its host’s evolutionary history.

Other geographically isolated populations, such as those found in Crete, California and Iran, were particularly useful in modeling dispersal and adaptation patterns.

Crete, for example, harbors predominantly htA despite its proximity to eastern regions, likely due to historical isolation and limited gene flow.

Californian populations share eastern Mediterranean symbiont and host haplotypes, supporting the hypothesis of human-mediated introduction from Turkey.

Similarly, Iranian populations show strong genetic ties to central Mediterranean populations, suggesting recent introductions and spread within the region.

The researchers believe that this deeper understanding of the genetic structure of olive fly populations and their symbionts can inform targeted interventions.

For instance, the distinct genetic profiles of Pakistani and South African populations may necessitate region-specific approaches.

The study also underscored the potential for leveraging symbiont biology in pest management, such as by disrupting the bacterium’s role in overcoming olive defenses.