Longnan Emerges as China’s Fastest-Growing Olive Oil Hub

Longnan, in China’s arid northwest, has become the country’s leading olive oil region, producing more than half of all domestic olives and investing heavily in mills, irrigation and farmer support.

Longnan is home to the largest olive oil mills in China. (Photo: Daniel Dawson)

Longnan is home to the largest olive oil mills in China. (Photo: Daniel Dawson) The article discusses the growth of China’s olive oil industry in Longnan, Gansu province, which is home to the country’s largest olive groves and mills. The region’s olive industry generates billions of Renminbi annually, supports hundreds of thousands of residents, and faces challenges such as drought, infrastructure, and competition from imports.

This is the third in a series of reports on the evolution of China’s olive oil industry.

LONGNAN, China – After leaving the industrial city of Guangyuan and passing through small villages and tunnels cut deep into the hills, the scenery shifts. Two and a half hours later, the train rolls into a drier valley: Longnan, often described as China’s answer to Jaén.

Chinese consumers’ ability to appreciate olive oil is improving.

Located in Gansu province, which has 1.17 million mu (78,300 hectares) of olive groves — 56 percent of the country’s total — Longnan is home to China’s largest mills and a rapidly expanding olive sector.

The city of 2.5 million people stretches along the curves of the Bailong River. Olive trees line parks, medians, roadsides and the steep terraces surrounding the valley.

Longnan, the epicenter of China’s olive oil industry, sits in a narrow river valley, with terraced olive groves surrounding the city of 2.5 million.

According to Bai Xiaoyong, chairman of Longnan Tianyuan Olive Company and secretary-general of the olive section of the China National Non-Timber Forest Products Association, the region’s boom began in 1975.

“In Wudu district, we received successful results after the first planting in the mid-1960s failed to bear fruit,” he said. “Since then, olive cultivation has spread across China in a second wave.”

Low humidity, scarce rainfall, ample sun and steep terrain have helped olive groves flourish for 50 years, earning Longnan the nickname “the hometown of Chinese olives.”

Tens of thousands of hectares of trees occupy terraces high above the valley and fill nearly every spare plot of land across the city.

Arbequina trees located on the terraced slopes above Longnan were laiden with fruit when Olive Oil Times visited in early November. (Photo: Daniel Dawson)

“The olive crop is used to alleviate poverty,” Xiaoyong said.

Mills pay farmers a fixed price of 7 Renminbi (€0.85) per kilogram this year. One mill manager said that before the government set a floor price, farmers earned about 3 Renminbi (€0.36), making the crop unviable.

“We make sure prices do not fall below 3 Renminbi per kilogram,” another mill operator said.

A former finance ministry official told Olive Oil Times that maximizing yields is not the sector’s primary goal. Instead, the focus is on redistributing state funds to rural areas and “promoting sustainable development.”

Official data show that Longnan’s olive industry generates 4 billion Renminbi (€485 million) annually and supports more than 400,000 residents.

During harvest, pickers set out at dawn, riding motorbikes up narrow mountain roads. With hand rakes, baskets and ladders, they work tree by tree across the terraces.

Many of the older orchards were never properly pruned. Trees now stand three to four meters high, slowing hand harvest and requiring teams of five or six workers to clear a single terrace.

Once complete, baskets are emptied into bins and loaded onto small trucks for transport to mills on the city’s edge.

Olives arrive at Olive Times’s mill in Longnan. Many olive mills in Longnan purchase olives from the local growers’ cooperative at a government-set price. (Photo: Daniel Dawson)

Most farmers belong to one of China’s few growers’ cooperatives, supplying all major mills, including award-winning Olive Times.

Owner Li Gang expects production to rise 20 percent this year, with yields reaching 700 to 1,000 metric tons.

“The yield of the trees has been increasing steadily,” he said. “The planting area is also increasing.”

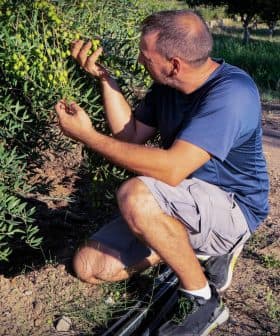

Olive Times owner Li Gang demonstrates how local farmers transport the olives along the steeply-terraced slopes to the nearest storage facility. (Photo: Daniel Dawson)

Longnan’s arid climate supports higher yields but increases drought risk. “In response to drought, we extract snowmelt from the Bailong River for irrigation,” Gang said. Hail, he added, is another persistent concern.

Local officials said regional and central authorities plan to invest 8.33 billion Renminbi (€1.01 billion) in reservoirs, canals and other infrastructure to irrigate 720,000 mu (48,000 hectares) of olive groves.

“With irrigation, yields per mu could rise from 200 – 300 kilograms to 700 – 1,000 kilograms,” a local official said. “This would raise per-mu value by 2,000 to 4,000 Renminbi (€245 to €485) and significantly boost farmers’ incomes.”

Beyond drought, officials pointed to weak infrastructure and high production costs. “Roads, electricity and irrigation systems are underdeveloped. Logistics are difficult,” the official said. “Fresh olives must be processed the same day, and transport bottlenecks restrict development.”

Early plantings also resulted in many low-yielding orchards. Domestic producers face tough competition from imports, limited technological innovation and branding challenges.

“The region lacks a unified public brand,” the official said. “Companies operate independently with limited impact, creating disordered competition and price confusion despite producing higher-quality oil than imports.”

To illustrate, I sit in the offices of Jianuidai China Co-Op, south of Longnan. Four plastic cups are lined up before me — three containing imported brands common in China. Based on my IOC-certified tasting training, all three exhibit clear defects. The least flawed might qualify as virgin, with fustiness registering at about a two.

By contrast, the oil made just 100 meters away is unmistakably extra virgin, though mild and produced from a mix of green and ripe fruit.

Gang said that improving Chinese consumers’ appreciation of olive oil remains slow work.

“The market is volatile, but consumption has risen steadily since 2018,” he said.

Olive Times sells nearly all its oil on the open market and does not participate in state-owned enterprise distribution channels.

The company has invested heavily in educating consumers about local extra virgin olive oil and sees gradual progress.

A historic center of Longnan, complete with a local olive oil shop, sits at the foot of olive-tree-dotted mountains. (Photo: Daniel Dawson)

Gang believes that as production increases, more consumers will taste the difference between local oils and many imported products. He expects this will strengthen trust in domestic production.

“Chinese consumers’ ability to appreciate olive oil is improving,” he said. “We believe these inferior olive oils will eventually be replaced in the market.”

Share this article