Olive Farming Is Key to Saving the Forests of Balochistan

Officials and environmental activists believe olive farming and oil production could help prevent illegal logging in wild forests.

Shrinking olive forests in Balochistan

Shrinking olive forests in Balochistan  7.6K reads

7.6K readsForests in Balochistan, Pakistan are shrinking at an alarming rate, with 80% owned by local communities and indigenous people. Efforts to combat deforestation include grafting Spanish and Italian olive varieties onto wild olive trees, with the goal of increasing olive oil production and economic opportunities in the region.

There is no doubt that forests play a vital role in combating the impact of climate change, mitigating floods, regulating weather and enriching biodiversity.

However, valuable forests in the poverty-hit Balochistan province of western Pakistan are shrinking, and forest degradation has continued for decades at an alarming rate.

If timely and concrete steps are not taken immediately, the remaining forests will disappear in the near future.

Spread over 347,190 square kilometers, forming nearly 44 percent of the total area of Pakistan, Balochistan shares borders with Afghanistan and Iran.

The estimated area of olive forests in the province is only 0.2 percent, with 80 percent of the forests owned by the local communities or indigenous people. The remainder is owned by the government and managed by its forestry department as state forests.

See Also:Pakistani Government Launches Agricultural Development ProgramThe most significant surviving olive forests are those under the control of the government.

Balochistan was once known for its rich forest cover. However, organized crime entities backed by local people have cut down many natural forests and transported the wood from one area to another.

A wild forest with grafted Italian and Spanish cultivars (Rafiullah Mandokhail for Olive Oil Times)

The matter has been brought to the attention of concerned authorities several times but to no avail.

In the northern parts of Balochistan – the Zhob, Sherani and Musakhail districts – the forests fall in the monsoon range climatically.

However, the people in this region are poor and have no alternative source for cooking fuel or heat in the winter. Pastures near the forest are also the only suitable places to graze their livestock. Wild olives are used as fodder.

While some local communities have pledged not to cut the forest, the economic pressure has left the marginalized communities with no other option but to cut and stock the olive wood.

Zhob – which borders Afghanistan and South Waziristan – is an area of lush green mountains and expansive and diverse forests. However, illegal logging combined with apathy from local officials means the wild olive groves are rapidly declining.

Hussain Alam, an activist in Zhob, said law enforcement is either absent or belongs to the same tribe, meaning they will not interfere with illegal loggers to avoid tribal feuds.

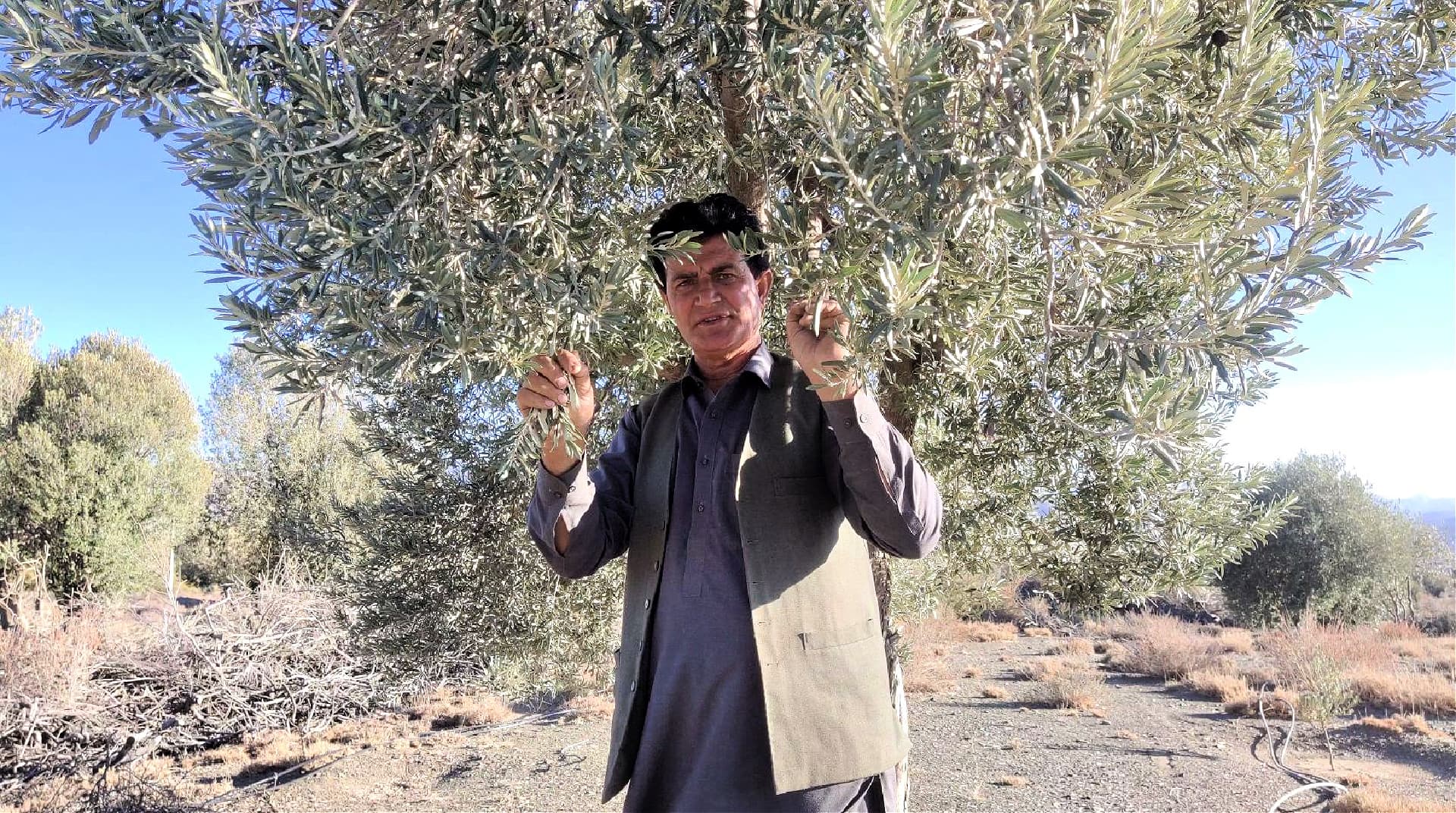

A local farmer, Abdul Qayum (Rafiullah Mandokhail for Olive Oil Times)

“The inhabitants in remote and hilly areas use the olive trees as firewood for cooking and burning purposes as fuel,” Alam said. “Likewise, they usually feed their cattle olive branches and fruit in the winter. The lack of availability of gas is one of the contributing factors.”

Forest and wildlife official Sultan Lawoon claims that poverty, illiteracy and unemployment are the main factors that have forced the local people to cut down the wild olive trees.

“The indigenous people not only cut the trees for fuel but also sell the wood in the open market to meet their needs,” he said.

Checkpoint on Balochistan-Khyber Pashtoonkhwa highway to control timber smuggling (Rafiullah Mandokhail for Olive Oil Times)

Environmentalists say deforestation has a tangibly negative impact on the area’s natural beauty and the number of endangered wild animals and birds.

Deforestation also contributes to drought, low rainfall retention, environmental pollution, erosion of fertile land and destruction of ecosystems and biodiversity.

They add that civil society and organizations working on the environment and forest conservation must take practical steps to protect these invaluable forests.

According to agriculture and forestry experts, if deforestation remains unchecked, these forests will become increasingly rare in the province. They argue that one solution is to improve local communities’ economic situation by promoting olive farming.

Sheikh Khaliq Dad Mandokhail, an assistant director at the local environment department, said planting olives is one of the best nature-based solutions to reduce the risks of climate change.

“If timely and concrete steps are not taken immediately, the remaining forests will disappear in the near future,” he said. “The Forest Department should be provided with better monitoring tools, locals should be provided with alternative fuels like gas and laws regarding the forest cutting needs to be changed.”

Abdul Qayyum is a resident of Ghbargei, in Sherani Balochistan, which boasts abundant wild olive forests.

He has grafted Spanish and Italian varieties with wild olive trees on about five hectares of olive trees in the local natural forest, which produces between 3,000 and 4,000 liters of olive oil annually.

“The grafting mechanism has been utilized in the hilly area,” he said. “During the last harvesting season, I managed to earn 1 million rupees (€4,700) selling olive oil.”

Qayyum believes there was no crop better suited to the region than olives as they are drought-tolerant and usually harvested in October.

The olives are harvested from the trees, and the extracted oil is transported to other parts of the country.

According to Forest Department statistics, wild olive forests cover 41,000 hectares of the Sherani district, of which 6,000 hectares are owned by the Forest Department. The local community owns the rest.

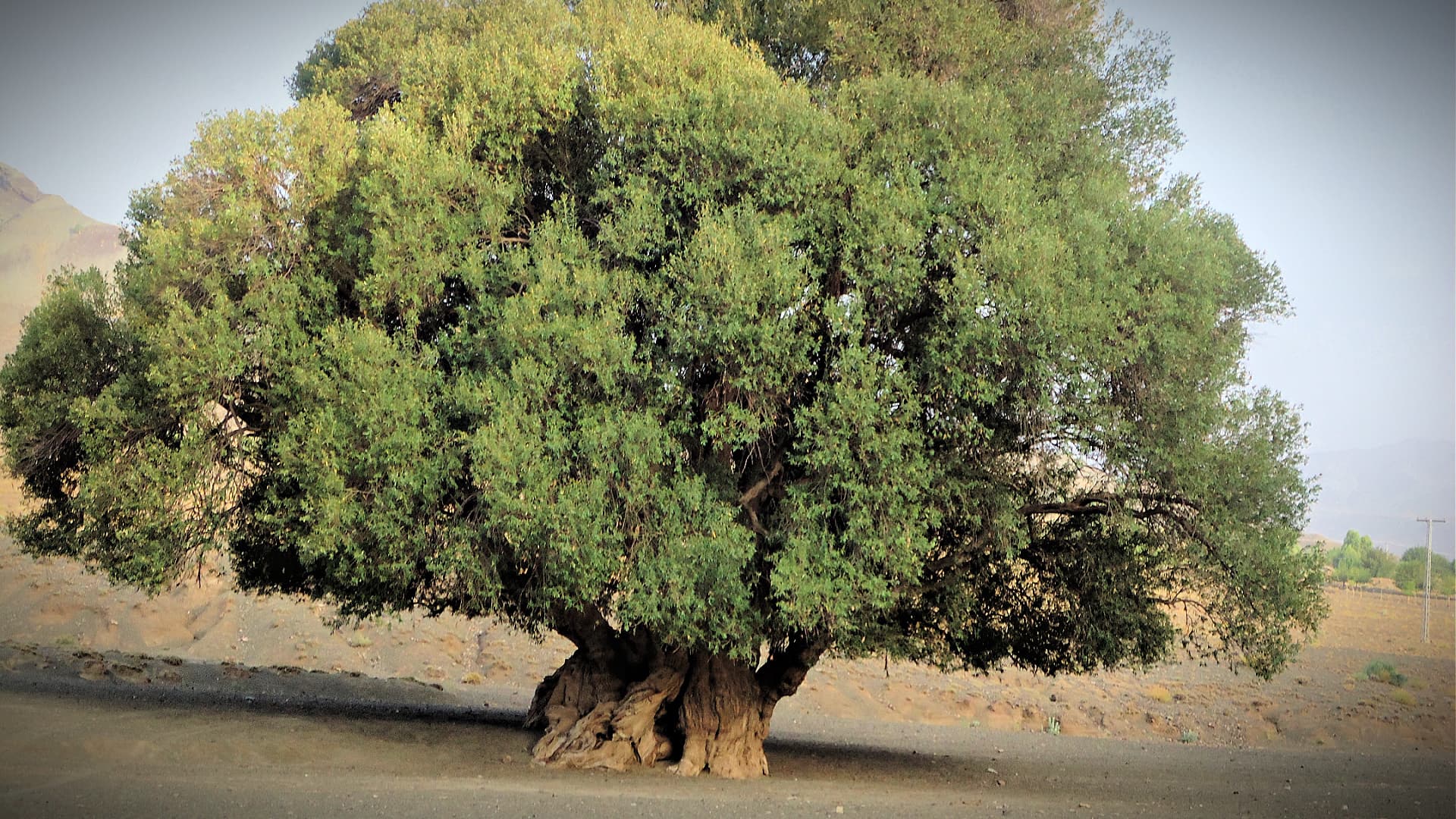

Centuries-old wild olive tree in Zhob Balochistan (Rafiullah Mandokhail for Olive Oil Times)

“To irrigate the olive trees, a drip irrigation system has been installed,” Qayyum said. “Twelve acres of natural olive forest were grafted with the help of the World Wildlife Fund and the UK-Aid funds, while the drip irrigation system has been installed with the help of the United Nations Development Program and the Agriculture and Water Management Department.”

Regarding the grafting method, Qayyum said the branches of the wild olive trees are carefully cut, and the Spanish seedling is attached. Then, the two are joined together with the help of clay and fastened with plastic.

“Grafting is usually done in spring or monsoon season,” he said. “There are millions of wild olive trees in Zhob. If grafting of Spanish varieties is done all over the forest, it will ultimately strengthen the people’s socio-economic condition and restore the lost beauty of the forests and landscape.”

Najeebullah Mandokhail, an agricultural official in charge of olive oil extraction in Balochistan, said that 50,000 olive saplings had been planted in different parts of Zhob in recent years.

Neighboring Loralai is the largest olive oil producer in the province. More than one million olive trees, including Spanish and Italian varieties, have been planted in the region. During the recent harvesting season, Mandokhail claimed that 62,000 litters of oil were produced in the region.

“One mature tree – irrespective of whether the variety is for olive oil or table olives – can produce 15 to 25 kilograms of fruit annually,” he said. “It takes, on average, 10 kilograms of top-quality olives to produce one liter of olive oil.”

Lawoon, the Forest Department official, said the age of the olive trees is between 1,500 to 7,000 years old.

Within three to five years, the olive branches begin to bear fruit. One hundred kilograms of wild olives yield 10 liters of oil, while one hundred kilograms of olives from grafted trees yield 22 to 28 liters of olive oil. There are 10 to 12 different olive varieties suitable for the climate of this region.

Officials and farmers in the South Asian county also see plenty of opportunity for olive oil production.

Pakistan, which spends 245 billion rupees (€1.16 billion) on importing edible oils yearly, has 3.17 million hectares of potential area for olive farming. This would allow farmers to produce olive oil for domestic consumption and exports.

The country recently became the 19th member of the International Oil Council (IOC). Officials in the sector say Pakistan has a production potential of 1,400 tons of olive oil annually based on current plantations.

In June 2022, Italy announced it would invest in developing olive cultivation and technical expertise in the two-year ‘Olive Culture’ project worth €1.5 million.

Italy had previously invested in Pakistani olive growing operations through the technical support of the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation in Pakistan.

There are already plans to expand olive production in Pakistan, with 3.6 million trees covering 12,500 hectares already planted and entering maturing and plans to plant 10 million more on an additional 30,400 hectares.

Balochistan is considered a highly promising province for olive tree cultivation and will boast more than 500,000 trees on 3,800 hectares by 2024. This alone is expected to generate 1.16 billion rupees (€5.5 million) by 2027.

Share this article