Debate Over Solar Plant Construction in Andalusian Olive Groves Intensifies

In Spain’s olive-growing region of Andalusia, plans to install solar panels on arable land have sparked protests from local farmers and civil society groups, with potential implications for the region’s olive oil production and economy. While the regional government argues that the renewable energy projects are in the public interest, campaigners are calling for a moratorium on the removal of olive trees and solar installations, highlighting the importance of traditional olive groves in reducing carbon dioxide emissions and food security.

In Spain’s olive-growing heartland, a clash between renewable energy ambitions and centuries-old agricultural tradition is escalating.

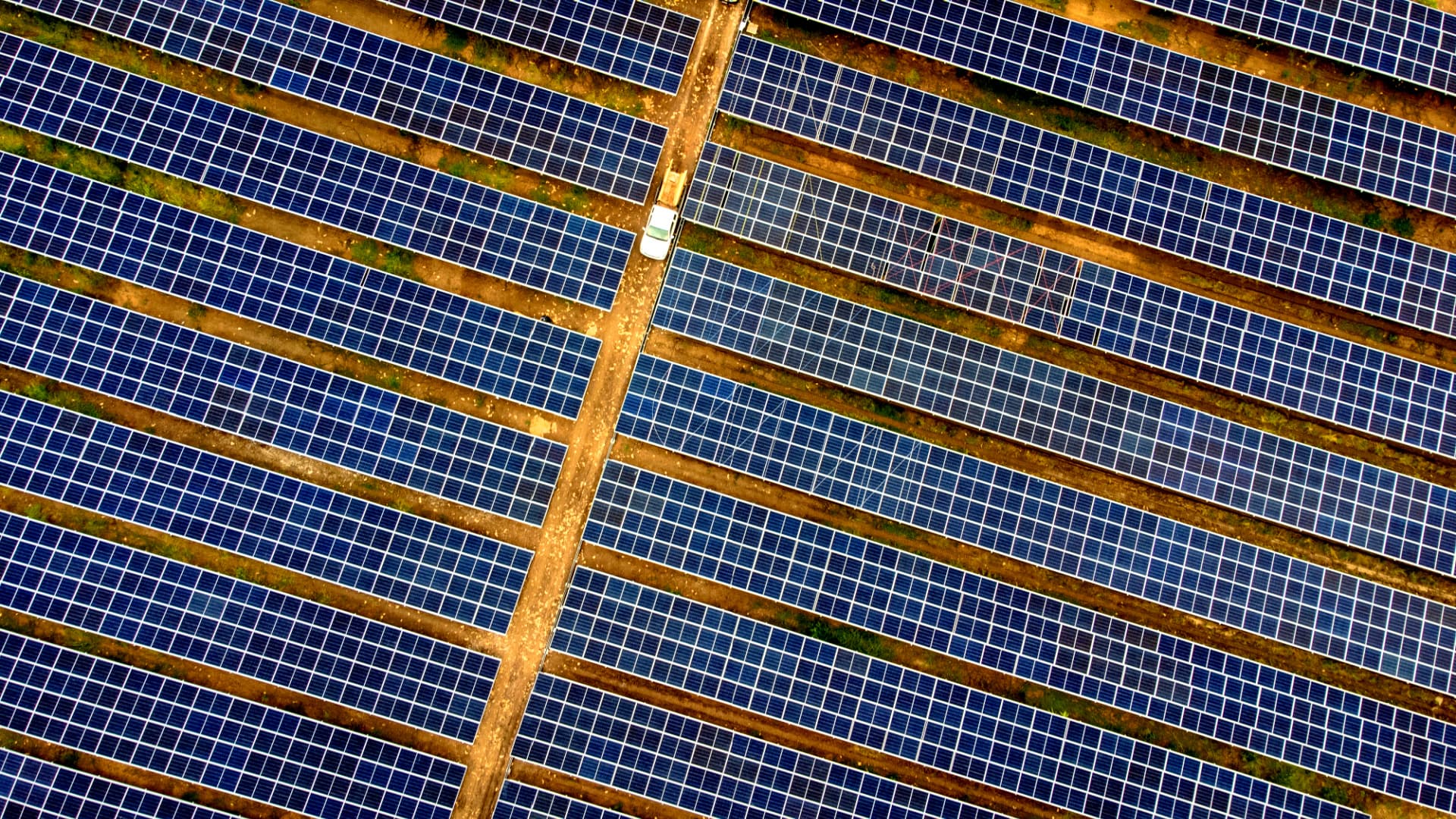

The country’s National Energy and Climate Plan sets a target of installing 76 gigawatts of photovoltaic capacity by 2030, of which 57 gigawatts is expected to be met with ground-mounted solar photovoltaic panels.

These panels are often installed as part of utility-scale developments, which usually require hundreds of hectares.

Wouldn’t it be more appropriate to prioritize locating these solar parks in deserts, rooftops, reservoirs, lakes, ponds, and other non-arable spaces, given how scarce and finite fertile land truly is?

In Andalusia, the world’s largest olive oil-producing region, which boasts nearly 3,000 hours of sunshine annually, the regional government has approved the installation of 25 mega-solar plants on 5,500 hectares of olive groves.

The announcement resulted in protests by local farmers across the Andalusian provinces of Jaén and Córdoba, with Lopera, Jaén, becoming a flashpoint.

Two solar developers have proposed multiple solar projects near Lopera, a small town dominated by olive farming, which campaigners estimate would cover 1,000 hectares of arable land.

See Also:Researchers Investigate Solar Panel and Olive Grove SynergiesDespite collecting more than 128,000 signatures calling for a moratorium on olive tree removal and solar installation in the region, the civil society group SOS Rural said the government plans to move forward with the plan.

“The regional government argues that the felling of olive trees has the support of society and complies with the law, but SOS Rural reminds them that we have collected more than 122,000 signatures in our campaign against the felling, that many owners have had their olive trees forcibly expropriated, and that the law used by [Andalusian president Juan Manuel Moreno’s] government as a shield is profoundly immoral,” said Natalia Corbalán, national spokesperson for SOS Rural.

Indeed, the regional government has declared the renewable energy projects to be in the “public interest,” allowing Andalusian authorities to pursue expropriation proceedings against holdouts.

Campaigners predict that the planned solar plants could result in the removal of about 42,000 olive trees, though officials estimate the number to be closer to 13,000.

The potential loss of olive groves has far-reaching implications. According to the local olive oil cooperative La Loperana, losing 500 hectares of olive trees would wipe out more than €3 million in wages and olive oil sales.

The issue of expropriation has ignited a political firestorm, with 50 affected farmers from Jaén meeting with a group of far-right regional lawmakers from the Vox party.

The controversy has also seen the left-wing Podemos party rally to the defence of the farmers, uniting both ends of the political spectrum against the conservative Andalusian People’s Party, with elections scheduled in less than one year.

In response to the growing backlash, Andalusian officials defended the process, insisting that locating the solar plants is the responsibility of the private companies involved in the process, with a variety of factors, including availability of grid connection and solar resources, playing a significant role in the decision of where they are located.

Despite the loud public spat, Juan Vilar, the chief executive of Vilcon, a Jaén-based consultancy to the olive oil sector, said solar plants currently take up a small percentage of the country’s fertile agricultural land, but this is already too much.

“Spain ranks seventh worldwide in installed photovoltaic park surface area on fertile land. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, these parks occupy 0.2 percent of usable agricultural land, about 50,000 hectares,” he told Olive Oil Times.

“To put that in perspective: Spain is the fourth largest producer of pistachios globally, and photovoltaic parks cover almost 60 percent of the surface area that pistachio trees occupy in the country’s agricultural footprint,” Vilar added.

Campaigners have also highlighted that traditional and century-old olive groves play a significant role in global efforts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions associated with climate change.

“[Traditional olive groves] allow 5.5 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent to be removed from the atmosphere for each kilogram of [unpackaged] oil produced,” said Lázuli Fernández from the University of Jaén, which is researching the carbon-capturing power of olive groves.

Meanwhile, Vilar further highlighted the potential damage that replacing productive crops and cropland with utility-scale solar could do to food security.

“According to a Snapshot Report, photovoltaic parks now cover 1.3 million hectares of arable land globally,” Vilar said. “That’s equivalent to the area planted with peach trees — the tenth most important permanent crop worldwide.”

“In other words, using this fertile land for solar parks rather than planting peach trees prevents the production of more than 22 million metric tons of this fruit,” he added. “Using peaches as a representative crop, the land covered by solar parks could otherwise yield 3.5 billion kilograms of food annually, enough to contribute meaningfully to feeding the more than 900 million people who suffer from hunger every day.”

Instead, Vilar believes there should be more focus on installing solar on rooftops and in marginal lands that are not well suited to agriculture.

“Wouldn’t it be more appropriate to prioritize locating these solar parks in deserts, rooftops, reservoirs, lakes, ponds, and other non-arable spaces, given how scarce and finite fertile land truly is?” he questioned.