Chile Celebrates Olives From Azapa

This year, the small, fertile valley achieved its hard-fought geographic indication, On the far northern edge of the Atacama desert, Azapa receives no rain, yet wells fed by the winters in the high plains above provide year-round water.

The short documentary Azapeña tells the story of the olive in Chile’s Azapa Valley, where olives have achieved a hard-fought geographic indication. The olives from Azapa are known for their vibrant color, high flesh to pit ratio, and traditional brine fermentation, and the region’s olive growers have formed a passionate association to protect their traditions and products.

“What does the olive mean to me?” asked Juan de Dios Araya, Parcela Gallo administrator. “Life,” he stated simply, in the recently released short documentary Azapeña, which tells the story of the olive in Chile’s Azapa Valley.

This year, the small, fertile valley achieved its hard-fought geographic indication, Olives from Azapa. More than half of the land there is used for cultivating olives, which are most notable for their vibrant violet color, high flesh to pit ratio, and simple brine fermentation. Azapa, on the far northern edge of the Atacama desert, receives no rain, yet wells fed by the winters in the high plains above provide year-round water.

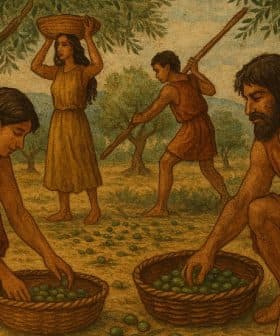

The groves trace their lineage back to Sevillian trees brought to Peru by wealthy Spanish settler Antonio de Ribera — but have since developed their own flavors and characteristics due to the local climate and natural processing. Afrodescendant people have played a huge role in cultivating olives here, and the groves are an integral part of their culture and way of life. ‘(Olives) give us everything, deliver all we need,” said Waldemar Hunaca Baluarte, also featured in Azapeña, directed by Daniela Echeverría Donoso..

More than 400 years after the first olives were planted in Azapa, Chilean President Michelle Bachelet conferred the geographic indication upon them, in May of this year. Azapa farms, virtually all of which are owned by area families, and range from just one to 50 hectares, can now benefit from this seal of origin on their olives, oils, and tapenades, protecting their authenticity, traditional production methods and preserving land and water for future generations.

Azapeña olives, while perhaps influenced by the cosmopolitan nature of the valley (the prominent Afrodescendant community, and those of Aymara indigenous heritage, along with colonial settlers from Italy, Spain, Greece and Croatia over the centuries), maintain the most basic of preparations, according to Roxana Gardilcic Boero, president of the Association of Olive Growers of the Azapa Valley (ASOVA).

“We only put the olive in water and salt,” revealed Gardilcic. “But aside from that, we have a climate that helps us. This climate allows for spontaneous fermentation,” a slow process, Gardilcic explained, that might take nine months or so, but preserves many of the nutritive elements of the olives, without using other chemicals or additives.

ASOVA was formed by a group of 35 passionate and dedicated olive growing families in 2012, and serves as a crossroads for tradition, family and the history surrounding the olive tree in Azapa. Over the past twenty years, Azapa growers have applied for the geographical indication four times, and finally achieved success in 2016, according to Chilean news source Chasquis.

Azapa Valley, Chile

The seal of origin is an important boon to olive growers in this region seeking to protect their traditions and their products, who in recent years have had to compete against multinational seed corporations making advances on Azapa lands.

“We have lived so long with the olive that even we don’t know the importance of what we’ve inherited,” stated Gardilcic, discussing the cultural significance of the olive in Azapa. Olives are part of Chile’s cultural and historical landscape, according to Gardilcic.

Hundreds of years ago the Spanish conquerors carried olives across the desert, intending to use the crude olive oil to illuminate the churches they built along the route to the silver mines in Potosí. “And so, what you have with the olive from Azapa,” Gardilcic said, “is a cultural heritage, it is a heritage because of its quality, and it is a product unique in all the world.”

File Upload