An Oasis of Award-Winning Extra Virgin Olive Oil in Tabernas

Sergio Leone, the Italian filmmaker, chose the desert region of Tabernas as a film location for his Spaghetti Westerns. Few believed the area was right for olive oil production.

Oro del Desierto

Oro del Desierto The Tabernas desert in Spain, known for its dry and extreme weather conditions, is home to a unique olive grove that produces aromatic and distinct olive oil due to the region’s climate. Despite challenges such as water scarcity, the family-run Oro del Desierto has implemented sustainable practices, including solar energy and natural herbicides, to cultivate their olive trees and preserve the environment for future generations.

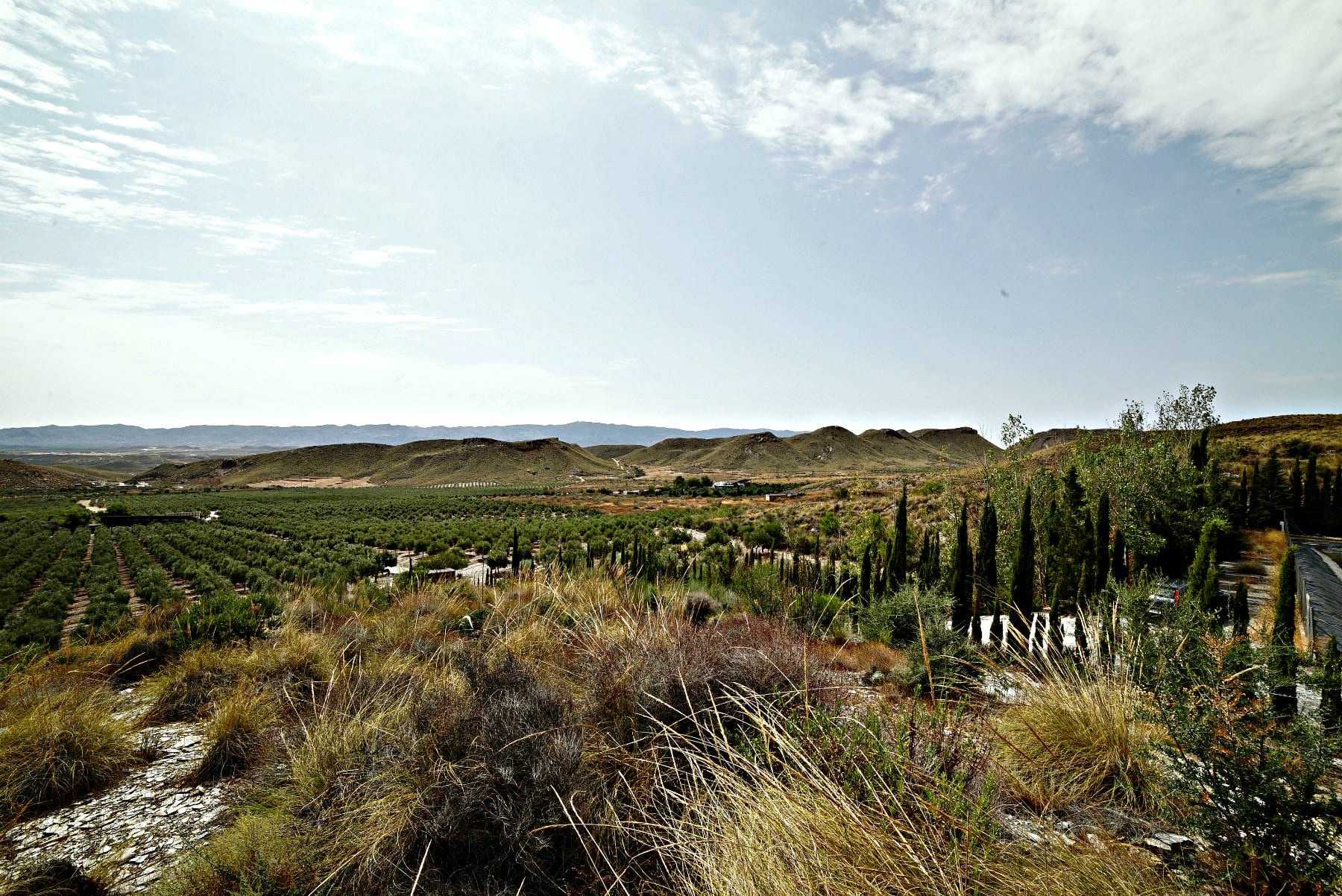

The esparto grass-covered hills and dry ravines of the Tabernas desert are not the usual backdrops to grow olive trees in Spain.

Sustainability is not only thinking about the environment. It is also thinking about the people who live in the environment. So it is something that we want to leave as a legacy.

With just 200mm of annual rainfall (7.8 inches) — less than that in the areas by the sea — and over 300 days of sunshine every year, this corner in the southeastern province of Almería is considered the driest place in Europe.

Its weather is extreme: the 400m (15748 feet) elevation above sea level makes temperatures vary from very hot summers to cool winters.

Sergio Leone, the Italian filmmaker, and many others chose Tabernas and its surrounding areas as a film location for Spaghetti Westerns.

The Mexican villages and the American far West landscapes where Clint Eastwood performed The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and For a Few Dollars More were, in fact, the old “cortijos” (Andalusian country houses) and villages of this long-forgotten region.

Growing olive trees and any other crops in this area requires special techniques and a good amount of determination.

As he drives through the 100-hectares (247-acre) olive grove, Rafael Alonso, export and marketing manager of Oro del Desierto (Gold of the desert), told Olive Oil Times that when his father started producing extra virgin olive oil in Tabernas 20 years ago, some people hesitated about the quality of the product he could obtain in this arid land.

In 2017, Oro del Desierto, which is still a family-run company, won a Gold Award and a Best in Class Award in the New York International Olive Oil Competition.

Traditional oil-producing provinces like Jaén, Córdoba, Sevilla and Granada are not far away, but the conditions in Almería are quite different. And they affect the features of the olive oil.

“Our region being so dry and having so much sun compared to other Mediterranean regions, makes our oil — I would not say better than others — but very different. Our oils are very aromatic, not too pungent, not as strong as others,” Rafael argues.

The Alonso family’s estate lies in a valley surrounded by bare mountains a few kilometres away from Tabernas, a village with a population of 3000.

“Water is the main concern here”, Alonso said.

“As long as we are in a desert, we need to irrigate the trees. We found several wells and that is the main source at the moment. But we are not far from the sea, around 30 kilometers (18.6 miles), and there is a project for bringing water from a desalinization facility in the future,” he added.

We have stopped at a spot in the middle of the estate. A group of horses seeks shade under a big solar panel. Both the animals and the energy-producing device play an important role in the way olive trees are cultivated here.

“We pump the water from the wells from between 16 – 18 meters (18 – 19 yards) underground thanks to solar energy. All the energy we use here is solar energy,” Alonso explained.

See Also:Buy Oro Del Desierto Organic Coupage

The 25,000-tree estate is irrigated by a dripping system. In most of the fields, the tubes are buried 40 centimeters (16 inches) underground to prevent evaporation.

Before dripping irrigation systems were applied, farming in this region was very scarce.

“This was mainly cereal land. Olive trees were grown just on the banks of the ravines so they could benefit from the water running through them once or twice a year. It was subsistence agriculture,” Rafael says.

Now things have changed. Although production rates are lower here than in other Spanish regions, intensive farming has become possible.

But Alonso, an Environment scientist who a few years ago decided to join his family’s olive oil production project, is a staunch defender of sustainable agriculture.

And this is the point where the small black horses that roam the estate are a valuable ally.

“They are very good combining with this crop because they don’t like the olives. They don’t like the trees so they don’t eat them, but they eat the weeds. So they are kind of a natural herbicide,” Alonso noted.

“Some people mistake them for ponies. But they are not. They belong to a race from Asturias, in Northern Spain, called asturcón.”

Despite the obvious constraints that they imply, constant drought and high temperatures also have some advantages for organic farmers.

“There was very limited farming and in a very traditional way. So there was no contamination and very little pressure in the ground. So it is a kind of virgin soil. So growing something in this kind of soil, and to be organics, is easier,” he said.

On the other hand, the lack of humidity makes it difficult for to spread and grow as fast as they would in more rainy areas.

The combination of four different varieties of olive trees on the estate — Hojiblanca, Picual, Arbequina and Lechín — also helps to prevent the impact of pests as each cultivar is affected by them differently.

20 years ago, when the Alonso family started producing organic farming, their project was seen as an oddity in the region.

Now, other farmers are producing good quality extra virgin olive oil in the Tabernas desert and, slowly, olive trees are changing this dramatic landscape.

“We strongly believe that sustainability is not only thinking about the environment. It is also thinking about the people who live in the environment. So it is something that we want to leave as a legacy.”

Share this article