Farmers in New Zealand Optimistic Ahead of Harvest

Olive growers in New Zealand are expecting a good harvest season for the third year in a row, with larger yields anticipated due to favorable weather conditions and improved farming techniques. Local growers are focusing on enhancing the polyphenol and antioxidant content of their extra virgin olive oils, while also working to combat diseases caused by high humidity levels in some regions. The country’s olive industry is growing steadily, with efforts to increase the consumption of locally produced extra virgin olive oils among New Zealand consumers.

Olive growers in New Zealand expect good results from the coming harvest season.

Local farmers confirmed that fruits are already dotting the trees in most groves, and this year’s harvest appears to be larger than the previous two.

It would be the third year in a row production has increased. About 200,000 liters were produced in the 2019/20 crop year, with 270,000 liters produced in 2020/21.

However, the expected growth does not surprise local experts since the weather has been favorable in recent months.

See Also:Former Fighter Pilot Steers Loopline Olives to the World StageSmall local growers also continue to learn more about preventing disease and overcoming challenges, resulting in growing yields.

“The managing of most olive groves is improving year over year,” Gayle Sheridan, Olives New Zealand’s executive officer, told Olive Oil Times. “We just had a field day with growers and witnessed the efforts that many have put into maintaining their groves, optimal pruning and caring for the health of their trees.”

During the biannual field days, the association visits olive groves in all the major growing areas of the country.

Some growers in New Zealand are focusing on adopting a harvest schedule that might enhance the polyphenol and antioxidant content of their extra virgin olive oils.

“It is an interesting phenomenon; analyses show how those contents are more present in local extra virgin olive oil as the consumers have also started to understand how beneficial they can be for their health,” Sheridan said.

To enhance the health profile of their oils, some growers are actively studying farming techniques that might improve the quantities of the healthy contents.

“They do not want to limit their activity to an early harvest, which usually ensures a good quantity of polyphenols; they are also investigating what other measures can be adopted,” Sheridan said. “It is an area for us that is quite new.”

The types of olive trees planted in New Zealand, most of which come from Greece, Italy, Japan and Spain, can also help farmers increase the number of healthy compounds in their oils.

“Frantoio is the most planted variety in the country,” Sheridan said, but Picual, Picholine, Pendolino, Kalamata and Koreneiki trees are also common.

“We do have a New Zealand variety known as J5, but we think it might have been derived from Frantoio as it looks like Frantoio,” Sheridan said.

Identifying the olive varieties that could better adapt to New Zealand’s specific climate has required time and effort for local growers.

Stuart Tustin, a tree fruit physiologist and plant and food researcher, told Olive Oil Times that “in the 70s and the 80s, many [farmers] planted varieties coming from Middle Eastern countries such as Israel.”

“But those trees did not adapt well to these latitudes,” he added. “Now, with most European cultivars, growers are seeing way more interesting yields.”

For its 300 olive farms growing 350,000 trees over 2,130 hectares, the New Zealand harvest season starts in April in the north and progressively moves south, where it should end by early August.

“Growers now know that they have to harvest at the right time and that the full crop has to be harvested not to have consequences on the following season,” Sheridan said.

See Also:The Best Olive Oils from New ZealandShe added that olive growers in the country produce exclusively extra virgin olive oil.

“Last year, we got 98 percent extra virgin olive oil,” Sheridan said.

Local extra virgin olive oil quality gets tested by specialized labs in Australia following International Olive Council’s protocols and standards for extra virgin olive oil.

The Olives New Zealand Association also releases the OliveMark trademark, which producers can adopt and show on their certified extra virgin olive oil containers. The goal of the trademark is to instill a sense of trust between the customers and producers.

Experts cite the consequences of a climate that brings significant rainfall in many areas as one of the main challenges for local olive farmers. When there are high humidity levels, several pathogens can take advantage of the climate and damage the olive trees.

The association suggests that growers actively combat the pathogens and spray their trees every 20 days.

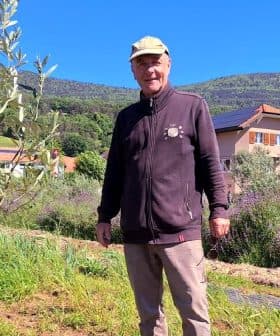

Stuart Tustin demonstrated pruning

“That is needed to keep on top of the diseases; otherwise, once you see them, it is too late,” Sheridan said. “Many proceed with relevant pruning operations, not just once a year as might happen elsewhere.”

“For instance, in these weeks, with the crop loads very visible, we suggest that many farmers prune the branches that do not have fruits, remove them and encourage new ones to grow,” she added.

According to Tustin, the parts of New Zealand that receive the lowest levels of rainfall are where olive growing is done most successfully.

“Those areas correspond to regions where other industries such as our wine industry are located,” he said.

Tustin emphasized how due to the maritime climate of the country, even the areas with less rainfall still report between 500 and 700 millimeters of rain each year.

While many farmers in the Mediterranean basin would be envious of the rain in New Zealand, the precipitation creates conditions for several diseases, including Spilocaea oleaginea

(peacock spot) or Cercospora.

“Those are heavily challenging pathogens because so many of our growers are small enterprises planted by people that did not anticipate that they would have to become… horticulturists,” Tustin said.

He added how many growers in the past did not practice disease control, experimenting with consequences such as leaf loss and reduced productivity. Not all of them pruned the trees correctly or at all.

“In such cases, we would find groves with trees out of control, complicated by a high disease pressure,” Tustin said.

That is why Olives New Zealand, Tustin and other local experts recently started a series of projects to restore several unhealthy olive groves, progressively removing excess branches. This allowed the light to come back on the trees while progressively reducing pests and pathogens thanks to correct pruning.

Tustin said that many growers have understood why the lack of pruning is a problem.

“In the last year, as some of those groves were full with their beautiful canopy on top, they have seen how trees that once produced between 10 to 15 kilograms of olives are now closer to 20 to 25 kilograms,” he added.

One of the most interesting research areas for Tustin and local experts is the need for some olive growers to find organic alternatives to spraying their trees with pesticides.

“Initially, they did not have sprays they could use, so we worked on developing organic-compatible spray programs,” he said. “To that end, I also contacted researchers from the University of Bari in Italy. We developed a spray program compatible with organic olive farming similar to what we use for organic apple disease control.”

“It is still too early to say how successful it is,” Tustin added. “At the moment, though, we see that its early results resemble those of the conventional spray program, which is quite encouraging.”

For local olive oil producers, seasonal markets are the best way to reach the consumers, Sheridan said.

“Those consumers want to know more about the product, how it is grown and if sprays are being used,” she added. “They ask questions and are very discerning about the olive oil they buy.”

Like other producing countries, local consumers might notice price differences between the extra virgin olive oils sold by the local growers and the imported brands found on supermarket shelves.

“Yes, we have imports from different countries, such as Spain or Italy, and the price difference is a bit of a challenge for us in making the consumers understand more about our extra virgin olive oils, the certification and the quality,” Sheridan said.

There are no high-density or super-high-density olive groves active in the country, while irrigation is present in about one-quarter of the total groves.

The largest three growers boast 40,000 trees, 27,000 and 7,000, respectively, while 70 percent of olive groves contain less than 1,000 trees.

Commercial groves, which can partner with supermarkets, represent 13 percent of the total in New Zealand. However, Olives New Zealand expects this figure to rise as more small growers partner with larger ones.

Those market dynamics paired with the enhanced productivity of the groves could also help the country improve the percentage of local extra virgin olive oils consumed in the country.

New Zealanders consume approximately 4.5 million liters a year, 10 to 15 percent of which is locally produced.