Italian Carbon Credit Supplier Receives International Accreditation

Italian olive growers and other farmers can now participate in the carbon credit market through the Alberami project, which has been validated by Carbon Check under the International Carbon Registry. The project involves implementing regenerative agriculture practices to maximize carbon credit production, with farmers receiving up to 75 percent of the profits from the sales of these credits.

Italian olive growers and other farmers can more easily enter the carbon credit market and benefit from a comprehensive regenerative agriculture approach.

The Alberami project has been officially validated by the Indian entity Carbon Check under the International Carbon Registry (ICR), allowing it to sell carbon credits internationally.

These credits come from the first group of Italian farmers adhering to the Alberami protocol, which aims to maximize carbon credit production in the field.

See Also:Trees Less Effective at Sequestering Carbon in a Hotter, Drier WorldAlong with olive growers, whose cooperation was crucial for the initiative’s launch, farmers who cultivate chestnuts, almonds, walnuts, carobs, citrus fruits, cherries, figs, prickly pears, pistachios, pastures and arable land will be able to generate and trade carbon credits under the scheme.

“When an olive grower or another farmer is interested in generating carbon credits with us, we guide them in the initial phase of choosing which agronomic practices to adopt,” said Francesco Musardo, the chief executive and founder of the Alberami project.

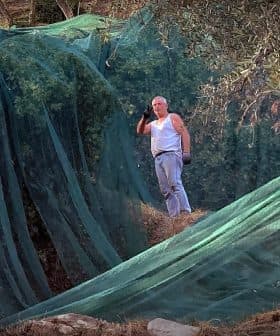

The brothers who run LiMatunni, a 19th-century olive farm in the southern Italian region of Puglia, were among the first to sell carbon credits through the Alberami project.

“Our entire approach to olive farming is organic and aims to let nature thrive,” Ascanio Sammarco, co-owner of the farm, told Olive Oil Times. “When we learned about the possibility of putting our carbon credits on the market, we didn’t hesitate.”

“We loved the idea as it connects a modern approach to agriculture, respectful of the environment, to tangible support for farmers,” he added.

The company manages olive groves in Erchie and Maruggio, in southern Puglia. It adopts organic farming practices in both areas, one of which has been severely affected by Xylella fastidiosa.

“To adhere to the limits and conditions of the Alberami protocol, we didn’t have to change much in our work,” Sammarco explained. “While everyone can join, those practicing organic farming will find it easier. Still, you must upgrade and add to your current practices to generate carbon credits.”

The Alberami protocol includes 13 practices inspired by sustainable and regenerative agriculture.

“Farmers must adopt at least three new agronomic practices from those listed in the protocol,” Musardo said.

“Soil sampling is conducted to establish a baseline, and subsequent samples are taken annually,” he added. “These, along with other factors, allow us to measure the issuance of carbon credits, which are then sold on the voluntary compensation market.”

Carbon credits are routinely bought by companies worldwide to offset the carbon footprint they produce. Carbon markets like the ICR provide the platform for such trades.

“The proceeds from these sales are shared with the farmers, who receive up to 75 percent of the profits,” Musardo said.

“While it depends on the farm and the practices, I would say that we are receiving an average of €250 per hectare,” Sammarco added.

According to Alberami, the more approved practices farmers implement, the higher the carbon credits their activity generates.

“Those who sign up for the Alberami protocols are also committing to a period of at least 15 years,” Musardo said.

The list of such practices includes transitioning to organic agriculture, zero or minimal tillage, greening the farmland, planting cover crops, integrating more than one crop in the same area, creating buffer strips, windbreaks and hedges along the edges of tree or cereal crops, reusing pruning remains and reducing synthetic fertilizers.

“Regenerative agriculture means restoring some of the organic matter content to the soil, nurturing it, and enhancing its fertility,” said Thomas Vatrano, agronomist, olive oil taster, and Alberami’s technical consultant.

“Whether it’s monoculture or the excessive use and abuse of mineral fertilizers, soil has been under siege for a long time,” he added. “While regenerative agriculture is a broad concept, we can summarize it as restoring the soil’s fertility.”

The Alberami project currently covers more than 1,500 hectares and involves 67 farmers. “Thanks to the validation, we are now entering a truly operational phase, so the more than 10,000 hectares on the waiting list can be unlocked,” Musardo said.

Within ICR, the Alberami project is now listed as “Agroecology Italy.” Musardo mentioned that they are already exploring opportunities to expand abroad.

“Once the methodology is established, it will be straightforward to scale it to other regions, in countries such as Greece, Lebanon, Tunisia or Turkey,” he said.

According to Alberami, the carbon credits being generated are now in demand by several entities.

“We are collaborating with companies in the United Kingdom, including an association football player, and with transport companies, financial institutions and pharmaceutical entities,” he said, hinting at agreements being finalized with other credit exchange platforms in France, Spain and Switzerland.

While the carbon credit market has been affected by significant abuses, the market-based solution to curbing greenhouse gases continues to be seen as an effective way to combat the causes of climate change.

The White House has announced new guidelines to strengthen the carbon offsets market in the United States. The European Union also considers carbon markets key to developing greener agriculture.

According to Musardo, companies are now much more attentive and discerning about the quality of the credits they buy.

“They seek high-quality projects that guarantee transparency and accountability,” he said. “Having one such project in Italy is particularly appealing for our agriculture, as all investments and profits stay in the country.”