Reflections on 45 Years Championing Italian Olive Oil in America

Nearly half of a century after a chance encounter with an Italian olive oil producer, John J. Profaci looks back on his role in the American market.

John J. Profaci at a salumeria in Italy circa 1979 (Images courtesy of the Profaci family)

John J. Profaci at a salumeria in Italy circa 1979 (Images courtesy of the Profaci family)  11.6K reads

11.6K readsJohn J. Profaci, an importer with forty-five years of experience, reflects on the rise of the olive oil category in the United States in an exclusive interview with Olive Oil Times. Profaci’s immersion in the olive oil trade began in 1978 after a chance encounter with Enrico Colavita, leading to a successful partnership that has grown into a worldwide family-owned enterprise, with Profaci’s sons now involved in various roles at Colavita USA.

In his forty-five years as an importer, John J. Profaci has witnessed first-hand the meteoric rise of the olive oil category in the United States.

“As soon as I start talking about the industry, my memory starts reflecting back on all the things that have gone by,” he told Olive Oil Times publisher Curtis Cord in an exclusive interview. “And I’m amazed at some of the things we did.”

(Enrico Colavita and I) trusted each other, and we both had a vision. We knew what we wanted to accomplish.

Profaci came from an olive oil family but did not become involved in the sector until his 40s. He worked as a broker, selling imported Italian foods to New York and New Jersey stores, when a chance 1978 encounter with Enrico Colavita, a producer and bottler, began Profaci’s immersion in the olive oil trade.

The two met in New York while Colavita was on his honeymoon and discussed the possibility of importing Italian olive oil to the United States. The meeting, over lunch at the New York Athletic Club, led to Profaci’s decision to go to Rome and meet Colavita to hash out the terms of a deal.

“I’d never traveled overseas before in my life, so the only problem was I didn’t have the kind of money to fly to Rome,” he said. As fortune would have it, Profaci’s friend was a travel agent for Eastern Airlines and agreed to get him a ticket on credit. “Of course, we flew economy class, and everybody was smoking,” he said. It was, after all, 1979.

Profaci found himself in a hotel near the Via Veneto in Rome. “I was supposed to meet Enrico the next day,” he said, “Now, I had no idea where we were going. He eventually showed up at the hotel, and we started driving to Molise.”

“I thought we were going to drive for maybe 15 or 20 minutes, I had no idea,” Profaci added. “We ended up driving for three hours.”

Sant’Elia a Pianisi circa 1979

Along the way, they passed Monte Cassino, a historic hilltop abbey founded in AD 529 and bombed relentlessly by Allied forces during the Battle for Rome in the Second World War, and a cemetery full of American soldiers. “That was very touching for me,” Profaci recalled.

After more driving, the landscape changed, with fields of olive trees dotting the rolling hills around the road. “He pulled his car over to the side, and we took a walk into the fields,” Profaci said. “It was very untidy and had not been cultivated for years, but the trees were there.”

“I said to Enrico: ‘Why is this so unkempt?’ He said, ‘John, there’s no place to sell the oil that we produce here.’”

By some estimates, the United States, a significant market for Italian exports, was consuming 50,000 tons of olive oil each year, one-sixth of what it consumes now. With most consumption limited to olive oil-producing countries, Italy had a surplus. Production exceeded consumption and drove down prices.

Colavita explained to Profaci that producing olive oil was not profitable, and the farmer could not afford to maintain, harvest, or fertilize the trees. “That was my first lesson about the industry,” Profaci said.

The two kept driving, passing through Campobasso before turning into the mountains and arriving in Sant’Elia a Pianisi, the Colavitas’ hometown about 200 kilometers southeast of Rome. There, Profaci was welcomed by Enrico’s mother, sister-in-law, and brother-partner, Leonardo.

“We had dinner. It was very nice, and they started to show me their plant,” Profaci said. “They had a big facility for producing olive pomace oil.” He visited mills in the region, all of which employed traditional hydraulic presses to extract the oil.

“The next day, we started visiting farms that produced the olives for the Colavita family,” he added. Profaci said the Colavitas sold olive oil in 55-gallon (210-liter) drums to local packers then. As it is known today, the Colavita brand did not yet exist.

“This was very interesting to me because I had never seen this work done before,” Profaci said. “That night, we were sitting in his office and talking about future business in North America.”

“He said, ‘John, I hope you can sell more than one container a year in the United States,’ and I said, ‘Well, I’m going to try’,” Profaci recalled.

Colavita asked Profaci if he had a brand in mind for the U.S., leaving open the option to use Colavita, which the company was already using for some other products. If not for his humble nature, one of the largest brands in the U.S. would perhaps today be branded Profaci.

Profaci left Italy with a handshake and gentleman’s agreement to sell Italian extra virgin olive oil to consumers in New York and New Jersey. “We were really unsophisticated in that type of negotiation, but we trusted each other, and we both had a vision,” Profaci said. “We both knew what we wanted to accomplish.”

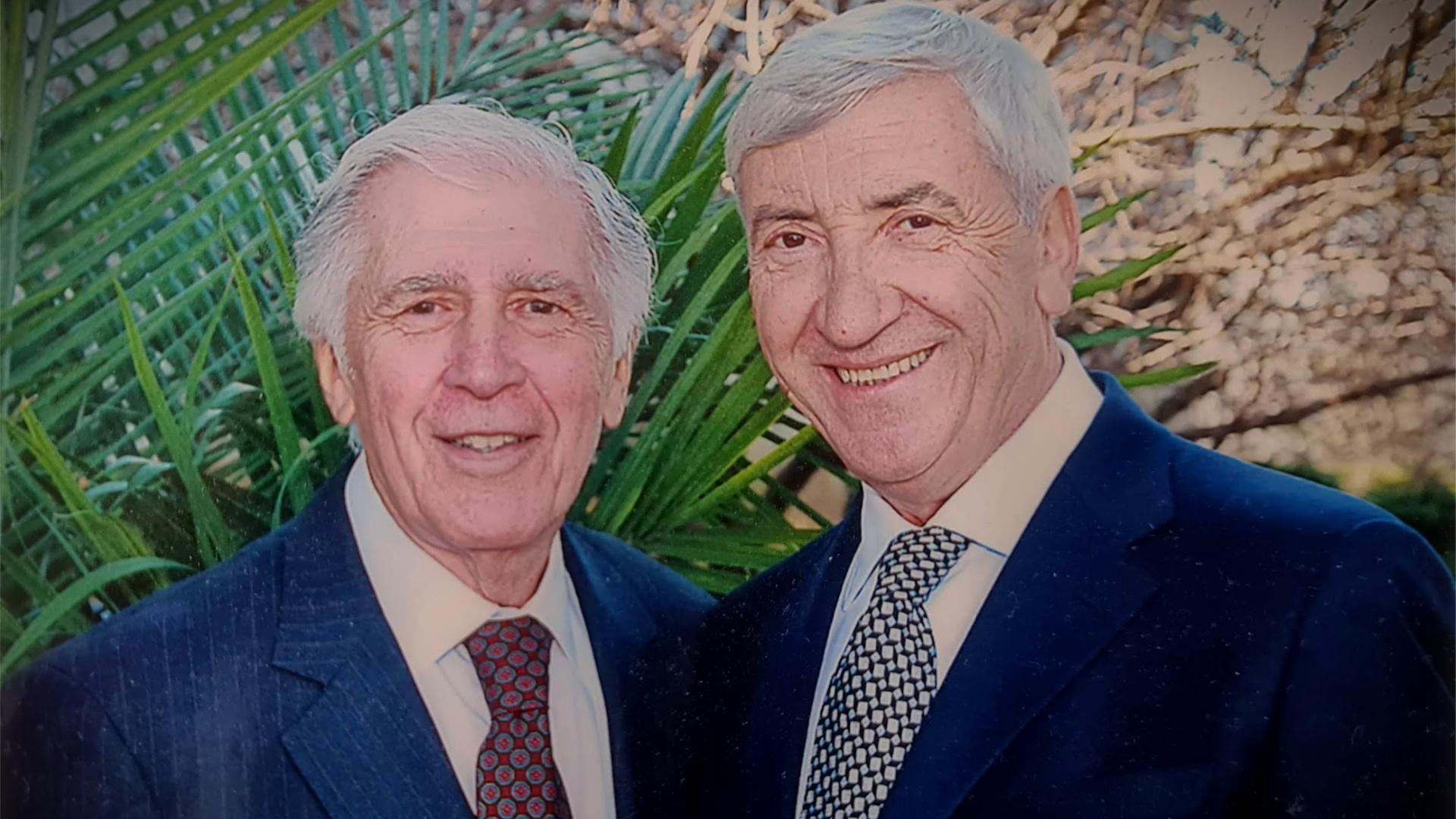

John J. Profaci with Enrico Colavita circa 2012

After a quick trip to Sicily to meet his extended family, Profaci said he returned to the U.S. excited to start the new business and determined to make it work. He made a good living as a food broker and took a considerable risk.

“I placed my first order with Enrico for a container,” he said. “At the time, the Italian government was paying all the companies a subsidy of 25 cents per liter [to help farmers sell olive oil]. Every container had 18,000 liters, so right off the bat, they were profitable.”

According to Carl Ipsen, a history professor at Indiana University who has studied Italian food and culture imports to the U.S., the Italian government subsidized local olive oil producers to help them maintain prices and compete with cheaper Spanish olive oil.

“When Italy joined the European Economic Community [in 1957], they maintained a high price for oil,” Ipsen said. “Spain wasn’t in the community yet, and Spanish olive oil was much cheaper. The Italian government was paying growers the subsidy so they could sell the oil and make it competitive with Spanish oil.”

The first Colavita shipment arrived in the U.S. in three-liter tins, which Profaci started selling to specialty food distributors in New York City. They were the first packaged containers of extra virgin olive oil branded with the Colavita name.

“Then I decided to go into the retail market,” Profaci said. A friend of his owned a Foodtown in Newark, New Jersey, and allowed Profaci to sell the extra virgin olive oil in the store.

“He said to me, ‘Come in on Saturday and set up your table,’ and I did, but it was very disappointing,” Profaci recalled. “For three or four hours, nobody showed up except for one lady.”

Profaci said the woman dipped some bread in the olive oil, tried it, and started to walk away. Profaci asked why she did not like the olive oil, and she responded that the flavor had been too strong and she did not like the burning sensation in her throat. It seemed Newark was not yet ready for extra virgin olive oil that retained the pungency of polyphenols.

“Then I decided that instead of retail, I should go into food service, so I took some bottles to Little Italy, and I went into this restaurant called Il Cortile, meaning the courtyard,” Profaci said.

Profaci met the owner, Sal Esposito, and told him that he had a product that he was very excited for Esposito to try. “He said to me, ‘Look, I know nothing about olive oil,’ and I almost said the same thing to him, but instead I said, ‘I have a good product,’” Profaci recalled with a laugh.

Esposito invited Donato Desiderio, Il Cortile’s chef from Bari, the capital of Italy’s largest olive oil-producing region, Puglia, where most of Colavita’s product is produced, into the negotiation. Desiderio tried the oil and recognized the quality. Thinking Profaci would not understand, he told Esposito in Italian to buy the extra virgin olive oil before Profaci had a chance to leave and sell it elsewhere.

Esposito was convinced and asked Profaci how much he was selling the olive oil for. Based on the tenor of the conversation, Profaci saw an opportunity. “Right away, I put $5 extra [$18.65 in today’s dollars] on the price,” Profaci said. “I had a price in mind, but because of the conversation, I put $5 on the case.”

Unfettered by the markup, Esposito ordered 25 cases. From that moment, Profaci decided selling to restaurants was the way to go. “So I started to build a business,” he said.

After the initial success at Il Cortile, Profaci decided to do some advertising for the product. “There was a publication called Attenzione, which was the first Italian-American magazine to hit the marketplace, and I took out an ad,” he said.

John J. Profaci, Enrico Colavita and Bob Bruno

Profaci decided to hire Bob Bruno as Colavita’s first marketing director, and the campaign he led was a success. Italians living in the U.S. and Italian Americans no longer had to rely on buying in bulk; they could now go to the supermarket and purchase Colavita extra virgin olive oil.

Sales soared, though they were initially confined to the Eastern Seaboard. Eventually, as the product became more popular, things started to change, and Profaci was selling to supermarkets nationwide.

He took his olive oil to the Fancy Food show in San Diego, California, where he met Irving Fine, who worked for a distributor that sold products to Florida-based supermarket chain Publix. Fine invited Profaci to Miami to discuss selling his olive oil in Publix. Profaci jumped at the opportunity. He had a second home in the area, and nearly everyone he knew in Florida shopped there.

At the time, Publix was expanding beyond Florida into other parts of the southeastern U.S. Profaci authorized Fine to offer Publix a deal. If Publix would buy one case for each store that would take the oil, Colavita would give them one case free. This way, Colavita became Publix’s first extra virgin olive oil and grew as the chain expanded.

“They started to move the product right away,” Profaci said, attributing the rapid sales to a good price point – $4.99 for a half liter – and a receptive consumer base.

Enrico Colavita, Alfred Ciccotelli Sr., Mario Colavita and John J. Profaci circa 1984

Since then, olive oil sales have continued to grow in the United States. According to industry data, nearly 20 percent of the cooking oils sold at retail in the U.S. by volume is olive oil, far exceeding the global total of three percent.

Profaci said Colavita set itself apart from the competitors by focusing on extra virgin olive oil while the other major brands in the U.S., such as Bertolli and Filippo Berio, were selling pure olive oil (a blend of virgin and refined).

Profaci was starting to tap into the consumer base that appreciated extra virgin olive oil’s bitter and spicy flavors, which are not present in lower grades since the phenolic compounds that make them pungent are eliminated in the refining process. Colavita soon started usurping other olive oil brands in long-established markets, betting consumers would pay higher prices for bolder flavors.

Another boost to the company’s fortunes came in 1981 when The New York Times wrote an article about extra virgin olive oil that featured a photo of a bottle of Colavita.

Colavita advertisement circa 1982

Subsequent stories in the Times investigated the benefits of olive oil consumption on cholesterol. They reported the findings of the landmark Seven Countries Study, which established the link between monounsaturated fat consumption and lower risk of cardiovascular disease.

Two “huge” benefits came from the articles, Profaci said: The free publicity of the photo and the changing narratives around the health benefits of extra virgin olive oil.

“In the 1950s and 1960s, the doctors recommended that you don’t use olive oil at all,” Profaci said. “They said it was bad for your heart, bad for your lungs and clogged your arteries.” The New York Times reporting started to shift the conversation and resulted in academics doing further research into the health benefits of olive oil, which, by some estimates, led to the boom in global production and continued prominence of the industry.

John J. Profaci with Julia Child at CIA circa 2003

Around the same time the articles were published, Profaci was already aware that education was one of the keys to increasing extra virgin olive oil consumption. To that end, Profaci and his son, Joseph R. Profaci, started to work with the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) in the 1990s when Ferdinand Metz was the institute’s president.

Like his father, olive oil is also in Joseph R. Profaci’s blood. He joined Colavita in 1993 as vice president and general counsel and is now the executive director of the North American Olive Oil Association.

At the CIA, Metz had a vision that Italian cuisine would overtake French cuisine in the eye of the American consumer. He wanted to build the institute to focus on Italian food and wine culture and was looking for sponsors.

“He reached out to every Italian company for sponsorship,” Profaci said. After several other big brands turned him down, the Profacis agreed to fund half the cost of the center, about $2 million split between Colavita USA and Italy, in return for naming rights.

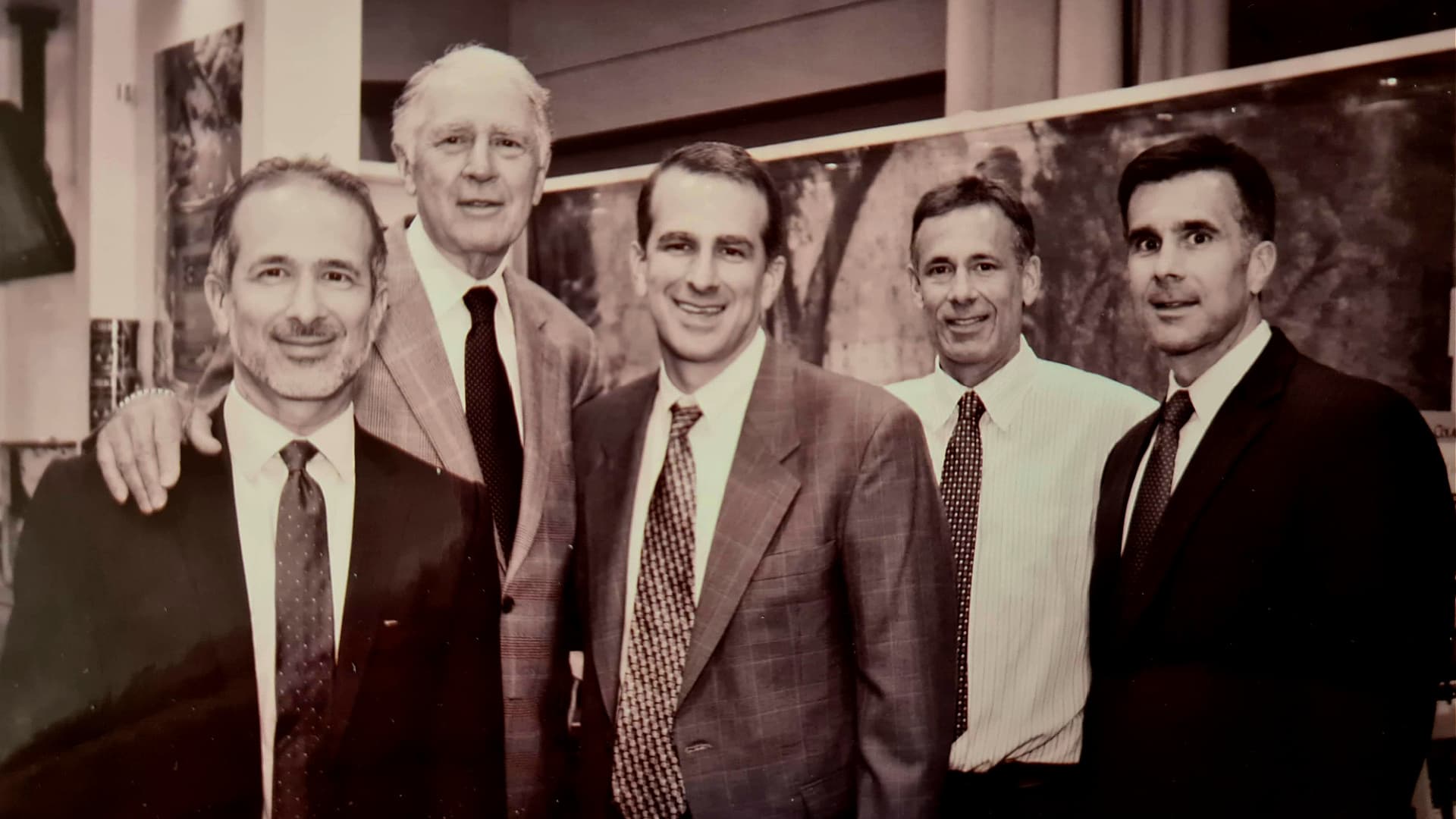

Profaci with CIA board chair August Ceradini and CIA president Ferdinand Metz circa 1995

In 2001, the Colavita Center for Italian Food and Wine was inaugurated on the CIA campus in Hyde Park, about 120 kilometers north of New York City.

While many European brands did not see the value of naming a building then, Profaci and his son did. “It’s a perpetual advertisement with 2,000 chefs a year going through the door,” Joseph R. Profaci said. “It was a no-brainer.”

With 45 years of perspective on the evolution of the U.S. extra virgin olive oil market, Profaci feels bullish about the future. Despite higher prices, consumption has remained strong, which Profaci attributes to the enduring popularity of Italian cuisine.

Even with record-setting prices, Profaci said he does not worry about consumers becoming disillusioned and swapping extra virgin olive oil for a lower grade or some other cooking oil. “Quality products always demand a price,” he said.

Profaci’s collaboration with Colavita has not gone unnoticed, with both men receiving recognition for promoting the United States’ burgeoning specialty food industry.

In 2009, Profaci was inducted into the CIA’s Hall of Fame and awarded the institute’s Augie Award. He was also named in 2015 among the inaugural inductees of the Specialty Food Association’s Hall of Fame.

Similarly, Colavita was recently honored as an ambassador of Italian cuisine at an event sponsored by the Italian Ministry of Agriculture, Food Sovereignty and Forestry.

Little did they realize at their first meeting in Molise that they were forming a partnership that would grow into a worldwide family-owned enterprise.

John J. Profaci with sons Joseph, Anthony, John and Robert circa 2012

Today, their legacy continues at Colavita USA, with Profaci’s sons, John A., Robert and Anthony, engaged in various roles. Colavita’s nephew, Giovanni, is now the chief executive, and his son, Paolo, heads the newly acquired California-based O Olive Oil division.

The Profaci-Colavita collaboration, born in Molise, was based on a gentlemen’s agreement for over a decade. The arrangement was not memorialized until 1993, when the parties signed a formal agreement acknowledging Colavita USA as the exclusive importer and distributor of the Colavita branded products, with Profaci as the chief executive. By 2010, the Colavita family had bought back most of the Colavita USA shares and now owns a majority of the company.

For his part, Profaci still goes into the office daily as chairman emeritus, though, he admitted, the schedule can vary depending on his tee time.

Share this article