9.6K reads

9.6K readsProduction

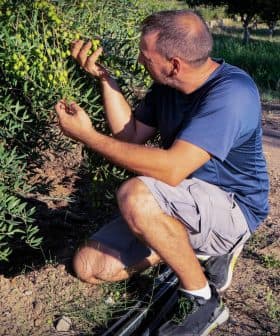

Olive Leaves Can Improve Oil Quality, Researchers Find

A study found that adding olive leaves during the olive extraction process can enhance the polyphenol content and sensory profile of extra virgin olive oil under specific conditions. Research showed that while the addition of olive leaves improved sensory attributes of the olive oil in a lab setting, it did not increase polyphenols or volatile compounds compared to olive oil produced without leaves.

A new study confirmed that under certain conditions, the addition of olive leaves in the olive extraction process might enhance the overall polyphenol content and sensory profile of the resulting extra virgin olive oil.

According to the research published in Food Chemistry, the combined extraction of olives and olive leaves in a laboratory environment introduced chemical and organoleptic changes to the extra virgin olive oil, which are different from those previously observed in an industrial setting.

See Also:Olive Oil Research News“We began working by modifying specific parameters of the extraction process, such as temperature, time, addition or not of water,” Ítala Marx, a researcher at the Instituto Politécnico de Bragança and University of Porto and co-author of the research, told Olive Oil Times.

“The following step was to co-extract olive oil with natural sources of phenolic compounds,” she added. “In this study, we analyzed the impact of the addition of 1 percent fresh olive leaves, co-extracted with Arbequina olives.”

The researchers decided on adding 1 percent of fresh olive leaves after observing that a small but undefined quantity of leaves ends up in the extraction process in most large-volume milling operations.

“From there, our team wanted to investigate what actually happens to the olive oil when such incorporation happens, in terms of sensory attributes, quality parameters, phenolic contents, volatile compounds,” Marx said.

The results of the experiment, which was conducted using a small-scale Abencor system, show that the resulting olive oil offers a significant improvement in sensory attributes — but reduced polyphenolic contents and volatiles — compared to olive oil produced solely from olives without the presence of any leaves.

However, previous research from the same academic team in an industrial setting demonstrated an improvement in sensory attributes and an increase in polyphenols, compared to olive oil produced solely from olives without the presence of any leaves.

“We attribute such different results to the different conditions of the two studies,” Marx said. “In an industrial setting, for instance, we were able to control operating temperature during the malaxation process, set at 22 ºC for 45 minutes, while in the lab setting, we had a 30 °C temperature during the malaxation process. And we also had different operational times.”

“In the industrial-scale research, with the same percentage of fresh leaves added to the process, we obtained olive oil which is rich both in phenolic contents than in volatile compounds,” she added. “In the Abencor laboratory-scale research, we have seen that olive oils extracted without leaves would have maintained a higher amount of the main phenolic contents, which did not happen on the industrial scale research.”

In the industrial scale experiment, recently published in the European Food Research and Technology journal, the researchers incorporated the 1 percent fresh leaves before the crushing process so that the contents were crushed together, obtaining particles of equal dimensions.

That did not happen in the Abencor system experiment, where the processed contents were reduced to smaller sizes using a small chopping machine.

“In such case, the surface contact is wider because the dimension is smaller,” Marx said. “The interaction among contents is therefore higher. Plus, the leaves were added before the malaxation process. So we believe that this is the most relevant difference between the two experiments.”

According to the researchers, the improvement to the olive oil derived from adding leaves is probably due to their chemical composition. They have not only a rich phenolic profile but also present enzymes destined to affect final quality.

Although, in the lab setting, with the Abencor system, the leaves did not increase the polyphenols and the volatile composition of the resulting olive oil. Both were higher in olive oils processed without leaves.

The researchers found that Abencor systems, widely used in research settings because they are smaller, cheaper and more practical, might not provide the complete picture.

“During the experiment with the Abencor system, we determined the enzyme pathways involved in the formation of the main phenolic elements, such as oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, oleocanthal,” Marx said. “We also focused on the lipoxygenases pathway, which is responsible for forming the main volatile compounds.”

“We focused on both these pathways finding how the integration of the olive leaves produced an interaction with these pathways but did not contribute to them, affecting them negatively instead,” she added. “So, our findings prove that the Abencor system, widely used in research for its accessibility and small scale, can not mimic the industrial-scale conditions.”

The Portuguese researcher also noted that previous research experimenting with the Abencor system and comparing the results with industrial conditions often found different results even when relevant factors, such as operating time or temperature, were the same in both settings.

“Many factors must be considered, such as oxygen exposure, superficial contact, size of hammer mills and even more, such as the separation during the centrifugation and decantation and more,” Marx said.

In the industrial scale experiment, the resulting extra virgin olive oil profile satisfied the most stringent quality parameters, while in the Abencor system, those results were not matched.

“It is interesting to note that in both settings, we obtained improved sensory attributes,” Marx said.

She added that the research team is already studying the impact on the olive oil profile deriving from adding olive leaf micro-organisms into the olive transformation process.