Olives with Higher Phenol Content More Resistant to Anthracnose

Changes in phenolic profiles during olive ripening play a crucial role in resistance to anthracnose, a disease caused by the Colletotrichum fungus, which leads to significant crop losses and renders contaminated olive oil unsuitable for consumption. Research conducted by the University of Córdoba’s olive genetics group found that varieties with high phenolic concentrations and specific phenols exhibit greater resistance to the fungus, providing valuable information for policymakers, farmers, and researchers looking to develop more resistant olive tree hybrids.

Scientists from the University of Córdoba’s olive genetics research group have found that changes in the phenolic profiles during the olive ripening process play a fundamental role in the resistance to anthracnose.

The economically damaging olive tree disease is caused by the Colletotrichum fungus. The fungus causes severe rot in olives, leading to significant crop losses.

Olive oil from olives contaminated by fungus has higher acidity and organoleptic defects. It usually falls into the lampante category and is unsuitable for human consumption.

See Also:Researchers Identify Three Olive Varieties Resistant to Pervasive Fungus“We analyzed six varieties for two years, carrying out analyses of phenolic compounds and resistance tests to the pathogen,” said Hristofor Miho, a PhD student at the University of Córdoba and first author of the study.

“The results allowed us to observe that resistance was greater in varieties with high phenolic concentrations and specific phenols present in them,” he added.

The researchers selected Empeltre and Frantoio cultivars, known for their resistance to the fungus; Hojiblanca and Picudo, known for their lack of resistance; and Barnea and Picual, considered moderately resistant.

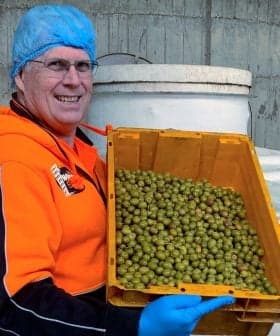

Olives were harvested from the World Olive Germplasm Bank of Córdoba before they began to ripen and at three ripening stages: green, turning and ripe.

Samples were taken to determine the olives’ phenolic profiles, and they were then inoculated using spores of the most common Colletotrichum strain found in Spain and Italy.

While all green olives are immune to the fungus, they accumulate inactive Colletotrichum infections in the form of appressoria, an organ-like structure that penetrates the fruit.

“This infection remains latent during fruit development until ripening, resulting in pathogen reactivation and disease development,” the researchers wrote. “Subsequently, olive fruit susceptibility to the pathogen increases during ripening, while in parallel, there is a decrease in total phenolic compounds.”

The researchers also isolated seven standard phenolic compounds to test their antifungal activity: hydroxytyrosol, tyrosol, oleuropein, oleuropein aglycone, oleacein, oleocanthal and hydroxytyrosol 4‑O-glucoside.

“Oleocanthal exhibited the highest inhibitory activity, followed by oleacein, oleuropein aglycone, hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol,” the researchers wrote.

See Also:Genotype Plays Significant Role in Fatty Acid Content of Virgin Olive OilOleuropein, ligstroside (the precursor of oleocanthal) and their derivatives, including oleacein, were the most critical compounds inhibiting spore germination.

The compounds are predominant in all green fruits regardless of cultivar and represent more than 90 percent of total phenols during ripening of the main resistant cultivars.

Meanwhile, susceptible cultivars converted oleuropein, oleacein and oleocanthal into hydroxytyrosol-4-O-glucoside as they ripened, which reduced anthracnose tolerance.

“Overall, resistant cultivars induced the synthesis of aldehydic and demethylated forms of phenols [oleuropein, oleocanthal and oleacein], which highly inhibited fungal spore germination,” the researchers wrote. “In contrast, susceptible cultivars promoted the synthesis of hydroxytyrosol 4‑O-glucoside during ripening, a compound with no antifungal effect.”

They further found that a total phenolic concentration of 50,000 milligrams per kilogram in all samples of developing olives across cultivars completely inhibited spore germination.

The researchers observed that cultivars susceptible to the fungus experienced a 73 percent decline in phenolic compounds during ripening, while resistant cultivars experienced a 28 percent decline.

“The sharp phenolic reduction of the susceptible cultivars caused the complete reduction of the antifungal activity,” they wrote. “Interestingly, the lesser phenolic decrease of the resistant cultivars did not reduce the inhibitory effect of spore germination.”

Juan Moral, who oversaw the research, said the study would help policymakers and farmers select new varieties to plant and inform researchers about what varieties to crossbreed for more resistant hybrids.

“Knowing how the phenolic cascades [changes in the phenolic compounds] behave in the different varieties will allow us to better select, based on scientific criteria, the parents that should be used so that the following generations of olive trees are resistant to this disease,” he concluded.