Spanish Scientists Advance Understanding of Devastating Olive Disease

A study led by researchers at the University of Córdoba analyzed 185 isolates of the Colletotrichum fungus, which causes anthracnose in olive fruit, with samples collected from various countries. The research found differences in sensitivity to fungicides between species, highlighting the need for more effective control methods to combat the devastating economic impact of the disease.

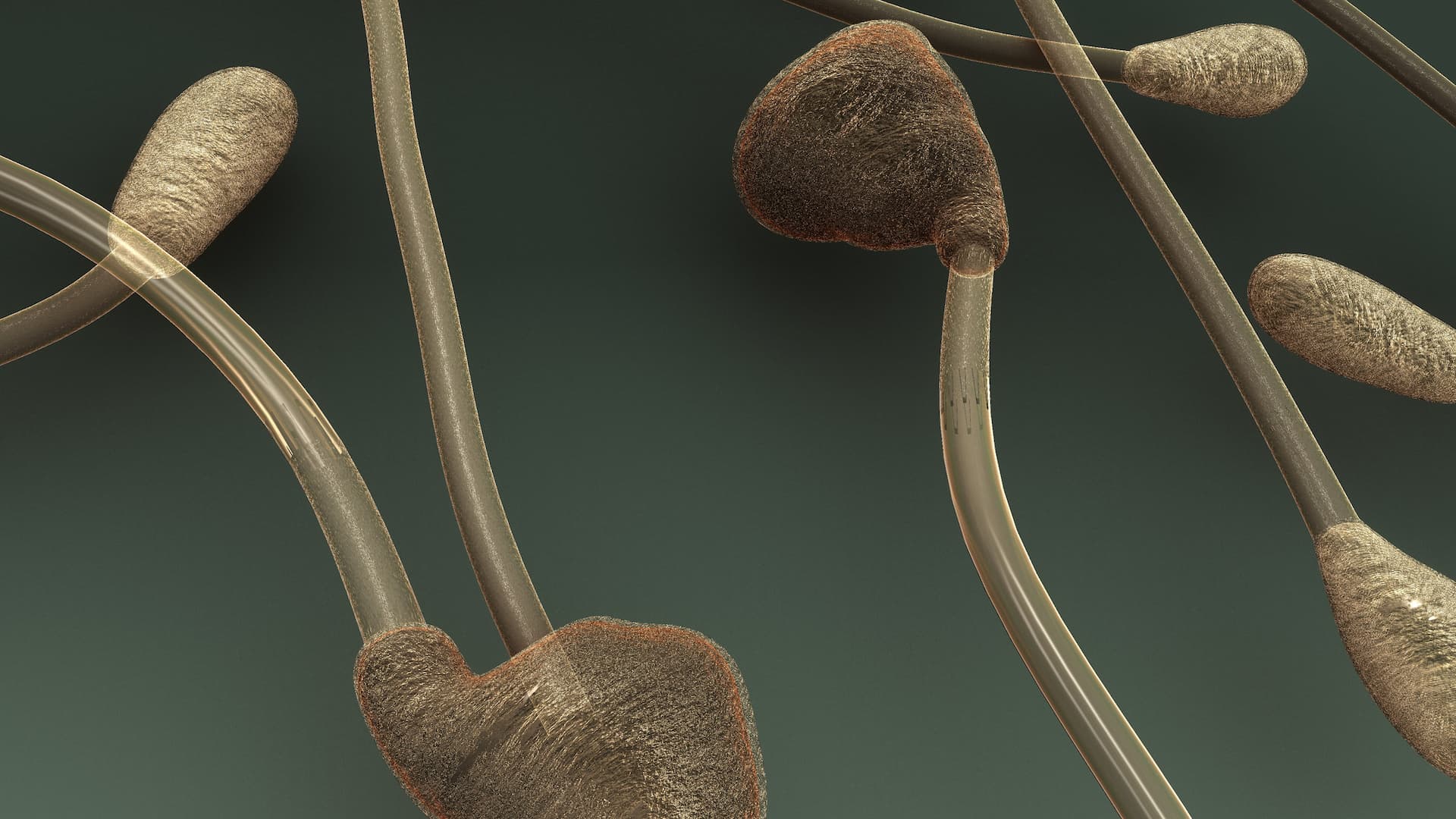

A team led by researchers at the University of Córdoba’s department of agronomy has published one of the most comprehensive studies to date into Colletotrichum, the fungus which causes anthracnose, or “soapy olive.”

Anthracnose in olive fruit is highly virulent and can cause crop losses of up to 100 percent. In addition, a toxin produced within the rotten fruit can weaken the trees themselves by causing the dieback of branches, thereby reducing future yields even after successful treatment. In Spain, the disease is responsible for an average annual crop loss of 2.6 percent.

In the case of Colletotrichum, morphological characteristics do not allow us to differentiate between different species, so we must resort to DNA sequences that tell us how similar some isolates are to others

In the study, a total of 185 isolates collected over a period of more than two decades were analyzed. Samples were taken primarily from Spain and Portugal, which are two of the world’s largest olive oil-producing countries. However, many other samples were collected from Australia, Brazil, California, Greece, Italy, Tunisia and Uruguay.

See Also:Olive Oil Research NewsWhile much prior research exists, molecular identification of isolates had not previously been carried out.

“In the case of Colletotrichum, morphological characteristics do not allow us to differentiate between different species, so we must resort to DNA sequences that tell us how similar some isolates are to others,” said Juan Moral, one of the leading researchers.

After using seven specific gene regions, 12 distinct species of Colletotrichum were identified.

Samples from other susceptible crops such as almonds, sweet oranges and strawberries, also were included in the study, and the fungus was found to be highly adaptable and opportunistic.

Isolates from Australian olive samples showed the highest Colletotrichum diversity by far, but with the two species dominant in Spain, Portugal, Greece and Italy being entirely absent. This adds weight to the hypothesis that native Colletotrichum species are able to rapidly jump to new hosts.

This ability of the fungus has practical implications for the prevention of the disease, as demonstrated by a case of cross-contamination at a nursery in northeastern Spain where citrus plants hosting the species C. fructicola are suspected to have infected olive plants which then showed necrosis of the leaves, a rare but potentially deadly symptom of anthracnose.

Given the pathogen’s devastating economic impact, various species were subjected to both benomyl and copper-based fungicides to determine their sensitivity and resistance.

“We have seen differences in sensitivity to fungicides between species and when we inoculated different varieties we also found differences in virulence between these isolates,” said Antonio Trapero, a University of Córdoba researcher.

Copper-based fungicides have become one of the most commonly used in recent years, due in part to their lower costs. However, results vary widely.

For example, the team observed that while the Spanish C. godetiae isolates from olive-growing regions where copper-based fungicides are frequently used by farmers were more tolerant to copper than C. nymphaeae isolates, samples from Portugal showed the opposite results.

“Having isolates from many countries shows how even isolates of the same species behave differently depending on the geographical area they come from,” researcher Carlos Agustí said.

The University of Córdoba said exploring the biology and biodiversity of anthracnose-causing pathogens in such depth should help advance the creation of more effective control methods.

The Spanish and Andalusian governments share this goal and both provided significant funding for the research.