How Farmers in Peru and Chile Work Together to Stop the Fruit Fly

Tacna in Peru and Arica in Chile are considered twin towns, with close ties due to family connections and shared history. Fruit fly outbreaks in Tacna are threatening centuries-old olive trees, leading to concerns about the impact on olive production in the region and prompting efforts to find solutions through international cooperation and research.

“Since time immemorial, Tacna in the south of Peru and Arica in the Azapa Valley in the north of Chile have considered each other as twin towns,” said Gianfranco Vargas, founder of Sudoliva, an initiative focusing on the preservation and recognition of century-old olive trees in the Americas.

Indeed, Tacna and Arica are only 40 kilometers apart. “It is common to find Tacna and Arica residents with family ties and properties in both locations,” Vargas said.

“Soon after the establishment of the Viceroyalty of Peru by Spain in the 16th century— when the first olive cuttings arrived in Lima from Seville — Azapa became an olive-growing valley, and before the War of the Pacific, the Azapa Valley belonged to the Republic of Peru,” he added.

Smugglers are bringing in fruit and vegetables from across the border from Peru into Chile and are doing much harm to the region and its farmers. The fruit fly is here to stay, and there is no insurance or subsidy to mitigate farmers’ losses.

Nowadays, olive producers from Tacna and Arica are involved in a complex interplay of trade dynamics that have been developing over the years along the border between Peru and Chile.

The latest news from Peru is concerning and involves a significant outbreak of the Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata) in Tacna this month.

“In 2007, the regions of Tacna and Moquegua were declared free of fruit fly, but flies have returned to Tacna and are now a problem,” said Rubén Centeno, president of the Association of Organic Olive Producers of Tacna (Aprecoliv).

See Also:New Tool Uses Satellite Data to Combat Olive Fruit Fly“Recently, they have been detected in sweet peppers, guabas, guava-pears and cherimoya, which are the fruits where fruit flies are most prevalent in this area,” he added.

Due to the lack of control of the Mediterranean fruit fly attack, which occurred in Tacna between 1925 and 1940, centuries-old olive trees had to be felled. This did not happen in Arica, where monumental trees are part of the rural landscape and a symbol of the Azapa Valley.

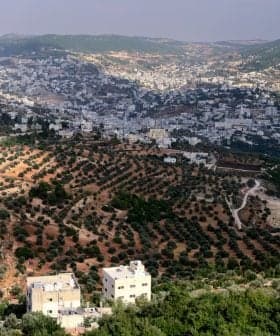

“Agricultural activity on both sides of the border takes place in a desert environment,” said Roxana Gardilic Boero, president of the Azapa Valley Olive Growers Association. “The area has a privileged coastal desert climate, with minimum rainfall and mild temperatures.”

Still, fruit fly attacks have been exacerbated in the past by extreme temperatures in a coastal ecoregion whose climatic conditions are influenced by the Humboldt current and the atmospheric interactions between the ocean and the mountains, creating a favorable climate for olive cultivation.

However, the area may be affected by El Niño-Southern Oscillation climate phenomenon — a recurring period of unusually warm sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean.

Due to the country’s natural configuration, surrounded by the Andes, the Antarctic ice, the Pacific Ocean and the Atacama Desert, the natural dissemination of the Mediterranean fruit fly is naturally prevented.

The only possible means of entry for the pest is the area in northern Chile, specifically the Tacna-Arica border, through the smuggling of infested fruit and the illegal entry of fruit via authorized border crossings.

According to official data from the Ministry of Agriculture, Chile was the only country in South America that was free from fruit flies in 2021.

The ministry warned that, due to the intense tourist and commercial traffic in the region, Chile is exposed to a constant risk from this pest, despite the strict surveillance measures it has put in place along the border.

The port of Arica, which operates as Tacna’s main port for exporting its olives and olive oil, is therefore also a sensitive area.

“The area has become a key economic driver, and there is a flow of tourists between Peru and Chile going through the Tacna border,” Vargas said.

Most olive growers in the Azapa Valley are fruit growers who also produce mango, papaya and orange, among other crops, and they are exposed to the Mediterranean fruit fly.

“Therefore, the risk of fruit flies affecting olives is always present because once the fly arrives, it has no other host and will attack the olive tree,” Gardilic warned.

“In the Azapa Valley, 98 percent of the 3,800 hectares of cultivated land are owned by small farmers on landholdings of less than five hectares,” she added. Moreover, “194 producers belong to the Azapa Valley Olive Growers Association and olive groves occupy 498 hectares.”

Across the border, in the La Yarada-Los Palos district of the Tacna region, olive production is far more important in volume compared with the Azapa Valley in Chile.

“In our district, crops cover 41,000 hectares and, of these, 31,000 hectares are devoted to olive growing,” said Alex Zeballos Maura, manager of Aprecoliv.

Aprecoliv brings together 47 associations and cooperatives in La Yarada-Los Palos, covering 10,500 hectares, 70 percent of which are organically farmed.

“The main problems we have in this area have to do with the fertilization methods and with conventional cultivation, apart from the incidence of several pests, including the fruit fly,” Centeno said.

“The fruit fly in La Yarada-Los Palos has had a significant impact on peach, avocado and grape crops, while for the olive crop, it is still under investigation,” Zeballos added. “SENASA — Peru’s National Agricultural Health Service, the phytosanitary agency of the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation — is currently investigating this issue, which is not a simple matter.”

SENASA has implemented a national fruit fly surveillance system, which includes campaigns aimed at eradicating the fruit fly and provides the essential data needed during negotiations related to maintaining and opening up new export markets.

However, SENASA is currently lacking sufficient funding since radical budget cuts have led to the layoff of field workers.

“As a result, it is no longer able to control the fruit fly efficiently. It has sent individual letters to all farmers informing them that they will no longer be responsible and that pest control will be the farmers’ responsibility,” Centeno explained. “SENASA has admitted that it feels overwhelmed and that it is proving very difficult to bring the fruit fly under control.”

Margot Ríos Mamani, Aymara National Councilor for Mallku and T’alla of Rural Arica, and an active member of several associations related to indigenous rural women, voiced her concern about the impact of fruit flies on the area.

“Smugglers are bringing in fruit and vegetables from across the border from Peru into Chile and are doing much harm to the region and its farmers”, Ríos said. “The fruit fly is here to stay, and there is no insurance or subsidy to mitigate farmers’ losses.”

She blames the lack of a regional strategy to fight against the fruit fly.

“There is considerable misinformation surrounding the fruit fly,” Ríos said. “Under Law nº 18.755 of 1989, as amended in 2022, provisions have been made concerning subsidies for farmers, and we consider that those affected by the fruit fly could benefit from them, although they have not been implemented so far.”

Together with Senator José Durán, Ríos has been working on the fruit fly problem in the Chilean Senate’s agriculture committee, addressing various issues of concern to farmers.

“We have been working on the fruit fly problem for many years to find ways to eradicate it in the region,” Durana said. “Agriculture is part of the regional development strategy and one of the most important economic sectors, both in terms of investment and job creation.”

“As a first line of action, we want to strengthen the regulatory framework,” he added. “Anyone who is currently bringing fruit or vegetables into Chile illegally is only receiving a fine. We are planning to toughen the penalties for smugglers so that their vehicle will be seized and they shall be liable to imprisonment.”

Durana also proposed helping mango and guava farmers, which are host crops of the fruit fly.

The lawmakers plan to present concrete proposals to the government by the end of April. Following talks with farmers, the aim is to establish a standard agricultural policy to protect both Arica and Tacna.

“We must continue fighting to ensure a level playing field for farmers affected by the fruit fly in the region of Arica and Parinacota,” Ríos said.

Trying to find alternative strategies to address these problems, Aprecoliv in Peru wants to focus on the role that the National Institute for Agrarian Innovation (INIA) in Tacna could play, in association with universities, private companies and the regional government.

“INIA’s research facilities in Tacna are huge, but they are currently in a state of neglect,” Zeballos said. “We would like to explore the possibility of allowing private companies working in entomology to conduct their research on INIA’s premises and collaborate with the universities.”

Even in Chile, “measures against the fruit fly never seem to be sufficient,” Gardilic said. “We feel that it is important that institutions like the Agricultural Development Institute take the necessary measures to protect our olive trees and support farmers, as agriculture feeds the world and nurturing the land is imperative.”

Sudoliva is currently exploring phytosanitary and technical solutions to prevent and tackle any fruit fly attack through an ongoing initiative in collaboration with the Tacna regional government.

They are currently discussing the signing of an international cooperation agreement with experts in fruit fly control from the University of California, Davis, Olive Center, as well as other universities and independent professionals based in California.

“The objective is to leverage their experience in the efficient management of this pest in Californian olive groves so that olive growers in Tacna and Azapa can control it efficiently and meet the necessary standard to export their products to the United States without hurdles,” Vargas said. “This would also reinforce importers’ confidence in the quality and safety of olives and olive oils from Tacna and Azapa.”