Drought, Worker Shortages and Roaming Boars: Challenges Mount for Italy's Farmers

Apr. 21, 2020 13:20 UTC

Apr. 21, 2020 13:20 UTCItaly is currently facing a severe drought, worsened by the national lockdown causing shortages in workers and supplies, leading to wild boars taking over deserted groves. The agriculture industry in Italy is undergoing an unprecedented stress test due to the Covid-19 emergency and the worst economic turmoil since World War II, with farmers facing a risk of reduced yields if adequate rainfall does not arrive soon. The industry is also struggling with a labor shortage, with seasonal workers from abroad unable to come, prompting the government to consider regularizing undocumented workers to address the issue.

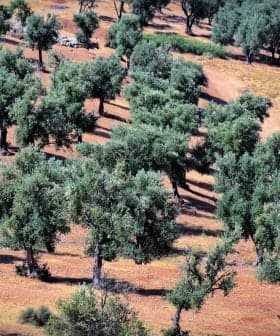

A severe drought plagues the country from north to south, the national lockdown causes shortages in workers and supplies, and deserted groves are now home for thousands of roaming wild boars. In the midst of the Covid-19 emergency and the worst economic turmoil since World War II, the Italian agriculture industry finds itself facing an unprecedented stress test.

If conditions do not change, and adequate rainfall sets in, many farmers will not have enough water for their crops.

Climatologists believe the current drought in Italy to be the worst such event in the last 60 years. In the northern regions, rainfall has dropped 61 percent since February. The latest data from the National Research Council shows a substantial reduction of water levels in rivers and lakes across the country, this is the warmest season on record since 1800, with temperatures 2.7 degrees (1.52 degrees Celsius) warmer than average.

While exceptionally severe, the drought is nothing new. Farmers association Coldiretti calculates that in the last 10 years, climate extremes have caused losses of more than $15 billion. Drought is the single most costly condition for the sector.

See Also:Producers in Spain Prepare for New Reality as Crisis Grinds On“To save crops, farmers are forced to intervene with emergency irrigation for corn and meet, while wheat, tomatoes, vegetables and alfalfa are under water stress,” Coldiretti stated in a press release. “If conditions do not change, and adequate rainfall sets in, many farmers will not have enough water for their crops, with a true risk of a strong reduction in yields at the worst possible time, when the coronavirus emergency has already slowed trade.”

But rainfall alone will not revitalize the industry. The Covid-19-fueled labor shortage predicted by industry watchers is taking its toll on thousands of small farmers. According to the Italian Ministry of Agriculture, seasonal agricultural workers coming from abroad usually account for 26 percent of the needed labor during the busy season. Farmers federation Confragricoltura estimated a labor shortage of at least 250 thousand workers while the workers union CGIL has openly discussed “a real risk of collapse of the sector.” Both Confragricoltura and Coldiretti have just launched their own web initiatives to find recruits for agriculture.

The Ministry called for quick action.

“Many invisible migrants work in our fields, live in informal settlements, are underpaid and exploited,” Minister Teresa Bellanova told Parliament. She estimated that “at least 600,000 people already work in our territories without paperwork” and asked for their regularization, a strategy that could address the labor shortage question and accompanying complex sanitary and social risks, but that has been met with skepticism by the parliamentary opposition.

Bellanova also noted the potential opportunities for seasonal workers whose contracts in tourism, restaurants and other sectors have been terminated because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Bellanova strategy has been met with interest by the workers’ unions.

“These workers must also be provided with suitable temporary housing. The Covid-19 emergency should not turn into a catastrophe for agriculture or a huge opportunity for organized crime; exploitation and underground work not subject to any sort of health and hygiene monitoring,” CGIL wrote in a note.

Business consultant Enzo Paladio told Olive Oil Times that bureaucracy is the biggest obstacle for agribusiness at the moment.

“We could have already found new seasonal workers among the many unemployed who have some form of public economic support, but actual rules do not allow them to receive that support if they are working on the fields,” Paladio said.

The workers’ union and farmers are asking the government to provide vouchers that could allow the unemployed to enroll as agricultural workers and speed up that process.

“That is just an example of the many obstacles we face,” noted Paladio.

To make matters worse, Covid-19 containment measures have hit agrifood machinery companies, with consequences for the whole sector.

“The prolonged stop to the agricultural machinery supply chain is hitting the farmers,” warned Coldiretti President Ettore Prandini. “Growers cannot find enough workers and do not have easy access to machinery supplies, agricultural equipment and spare parts, all [of which] is needed to work in the field.”

And while unions, associations and government struggle to find and implement solutions, wild boars are seizing the opportunity to roam in unworked fields. In several areas of the country, farmers have warned of large herds of boars and other animals wandering through agricultural lands. The road to recovery for the agribusiness sector will also have to lead them away from the crops.

Paolo DeAndreis

Paolo DeAndreis