Using Technology and Old Photos to Map Erosion in Jaén's Olive Groves

Researchers at the University of Jaén have developed a new method for analyzing soil erosion in olive groves, using aerial photographs and LiDAR data to create digital surface models. By comparing DEMs from different time periods, the researchers found significant soil erosion in olive groves in Jaén, with soil losses of up to 50 tons per year for every 2.5 acres, a rate that may increase due to changing rainfall patterns and management policies.

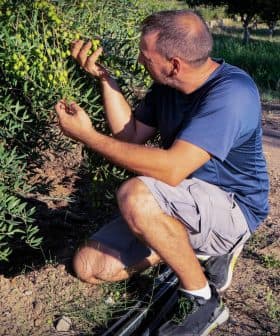

A new method for analyzing soil erosion and its impact on olive groves has been developed by the researchers at the University of Jaén.

A better understanding of how the groves’ soil changes over time – its composition, volume, shape and other characteristics – may offer growers a new set of tools to plan their operations.

Considering these findings, we suspect that an acceleration in the soil erosion process is on its way, probably due to the effects of infrastructure, different policies in the managing of the territory as well as the changing rainfall.

The team, from the university’s center for advanced studies of Earth sciences, energy and environment, studied aerial photographs taken over several decades to evaluate the changing soil conditions of the olive groves.

“The aerial photographs collected either by conventional aircraft platforms or drones were coupled with LiDAR (Laser imaging detection and ranging) data to make digital surface models,” Tomás Fernández, one of the authors of the study, told Olive Oil Times.

See Also:Research NewsHe added that these digital elevation models (DEMs), “are accurate representations of the ground heights.”

By comparing DEMs obtained from decades of aerial photographs and LiDAR, a whole new set of data was created

“In Spain, we’ve had periodical aerial flights over the territory since 1956. Since 2004, this has happened every two or three years, and drone flights can be operated when needed,” Fernández said.

“Therefore, we could compare DEMs from different dates and the result of this comparison, the differential DEMs, allows us to identify areas in which the ground surface decreases – the erosion areas – and locations where the ground surface increases – the deposition areas,” he added.

By quantifying these areas and the erosion or deposition heights associated with them, researchers were able to evaluate the volumes of material involved in the changing soil shapes.

“We have calculated an increase of two inches per year in some sectors of the gullies from 1984 to present, and soil losses of 50 tons per year for every 2.5 acres, almost twice the estimated annual average losses in the province of Jaén,” Fernández said.

The researchers also determined that during peak periods, when soil erosion accelerated, such as from 2009 to 2010, the rate of erosion reached 20 inches per year with a total loss of 450 tons per year for every 2.5 acres, a tenfold increase when compared to the average losses that were estimated by experts and farmers before this study was completed.

“Those are values to be taken into account because they cause very significant losses of fertile soil, as well as very significant damage to crops and infrastructure,” Fernández said.

Researchers also found a correlation between soil erosion in olive groves and periods of increased rainfall – a finding with a twist.

The researchers noted that soil erosion in periods of heavy rainfall had a more noticeable impact in recent years, such as from 2009 to 2013, when compared to similar rainfall patterns from earlier time periods, such as from 1996 to 1998.

“Considering these findings, we suspect that an acceleration in the soil erosion process is on its way, probably due to the effects of infrastructure, different policies in the managing of the territory as well as the changing rainfall,” Fernández said.

While the study was conducted in a specific olive oil producing region, the method devised by the researchers can be applied to other relevant territories as well.

“The technique can potentially be applied everywhere, at least where aerial photography of the territory and LiDAR data can be made available,” Fernández said. “Should these data not be available, a historical investigation is not possible.”

“Still, actual and future evolution in the soil erosion can be addressed by means of drone flights or terrestrial photogrammetry and LiDAR,” he added.

Their study could help better understand what the researchers believe is a “current major problem at the global level, which has a relevant impact in Mediterranean countries and, locally, in the olive groves of Jaén.”

A problem, they said, “which may critically increase in the coming years.”