On Stromboli, Olive Trees Help Restore Land, Community and Tradition

A community-led olive cultivation project on Stromboli is restoring terraces, stabilizing slopes and reconnecting residents with the island’s agricultural heritage.

Stromboli Island (Photo by Charlotte Gabay)

Stromboli Island (Photo by Charlotte Gabay) Attiva Stromboli is leading an initiative to revive olive cultivation on Stromboli Island, which aims to restore the landscape, regenerate the soil, and strengthen community networks. The project involves planting olive trees, restoring dry stone walls, and reshaping land using traditional techniques, with the goal of promoting sustainable soil management on Mediterranean islands. Despite challenges like wildfires and floods, the association has made progress in reclaiming land, restoring terraces, and reintroducing olive trees and caper plants to enhance biodiversity and support the local economy.

On Stromboli Island, the northernmost of Sicily’s Aeolian archipelago and home to the eponymous volcano, the revival of olive cultivation is helping to safeguard the landscape, regenerate the soil and strengthen local community networks.

This is a one-of-a-kind environment, defined by the presence of one of the world’s most active volcanoes.

The effort is being led by the non-profit association Attiva Stromboli, which combines the recovery and planting of olive trees with the restoration of dry stone walls and the reshaping of land using traditional hydraulic techniques.

A study conducted by the University of Tuscia recognized the initiative as a best-practice model for sustainable soil management on Mediterranean islands.

“This is a one-of-a-kind environment, defined by the presence of one of the world’s most active volcanoes,” Paolo de Rosa, legal representative of Attiva Stromboli, told Olive Oil Times. “It is a fragile ecosystem that is also threatened by the loss of land management, a widespread phenomenon that has affected marginal areas since the mid-20th century due to emigration.”

As on many other Italian islands, tourism began to develop on Stromboli in the 1950s, gradually reviving the island’s economy.

Today, tourism is the island’s primary economic driver. Stromboli has roughly 500 permanent residents, and while its crystalline waters attract thousands of visitors in the warmer months, many also come to see “Iddu,” the affectionate local name for the volcano. Hiking tours led by licensed guides are among the most popular ways to explore its slopes.

Founded to promote the territory and its culture, Attiva Stromboli launched a 2018 project to establish a community olive mill and revive olive cultivation as a first step toward restoring and enhancing the landscape.

The project led by the non-profit association Attiva Stromboli combines the recovery and planting of olive trees, the restoration of dry stone walls, and reshaping of the land using traditional hydraulic techinques.

“Beyond tourism, agriculture had been sidelined and the landscape largely neglected,” de Rosa said. “It was necessary to intervene to restore ecological balance. Starting with olive cultivation was natural, as it had once been central to the island’s economy, which in the 1930s counted five active mills.”

After the presses were dismantled, growers were forced to load their olives onto ferries and ship them to off-island mills. Frequent weather disruptions often delayed processing, compromising oil quality.

“Instead of relying on external facilities, a social oil mill allows us to produce directly on the island and encourages greater care for the olive trees,” de Rosa said.

With support from the Sicily Environment Fund and several private donors, the association purchased a state-of-the-art mill equipped with Mori-Tem technology.

The initiative also reached private villa owners with ornamental olive trees. “We proposed agreements under which we would prune and harvest the trees,” de Rosa said. “Many residents then began caring for their trees independently and recovering abandoned ones. This helped achieve one of our main goals: that the community itself protects the island’s land.”

Researchers recognized the project led by Attiva Stromboli as a best-practice model for sustainable soil management on Mediterranean islands.

Over time, production tripled and participation grew from 10 to more than 30 people. Between 100 and 150 bottles are now produced annually and auctioned during a harvest festival, with proceeds reinvested in the project.

The initiative, however, could not shield the territory from the scale of a human-caused wildfire in May 2022, which destroyed 200 hectares of vegetation, following earlier blazes linked to eruptive activity in 2019 and 2021.

“We are used to wildfires caused by volcanic activity, but that blaze was enormous,” de Rosa recalled. “What moved me most was the collective response and the solidarity shown in protecting both people and land.”

The fire was followed by a major flood in August, exposing severe hydrogeological instability.

“We realized that beyond recovering damaged olive trees, we needed to work systematically, restoring terraces so water could flow and drain properly,” de Rosa said. “We used the momentum from these events to raise funds for coordinated land reclamation, particularly in the upper areas above the village.”

With renewed support from the Sicily Environment Fund and contributions from private donors and professionals, the association secured resources to purchase equipment, recruit volunteers and hire a seasonal worker. Operations began in November 2022.

So far, one hectare has been reclaimed. The work included restoring dry stone walls, building slope-stabilization structures and firebreaks, pruning and planting olive trees and caper plants, restoring an old cistern and installing a new irrigation system.

The group recovered centuries-old olive trees and planted about 200 Nocellara Messinese saplings, aiming to reach at least 500 trees in the long term.

They also introduced caper plants (Capparis spinosa), propagated from local cuttings and seeds, to preserve biodiversity and create a resilient intercropping system.

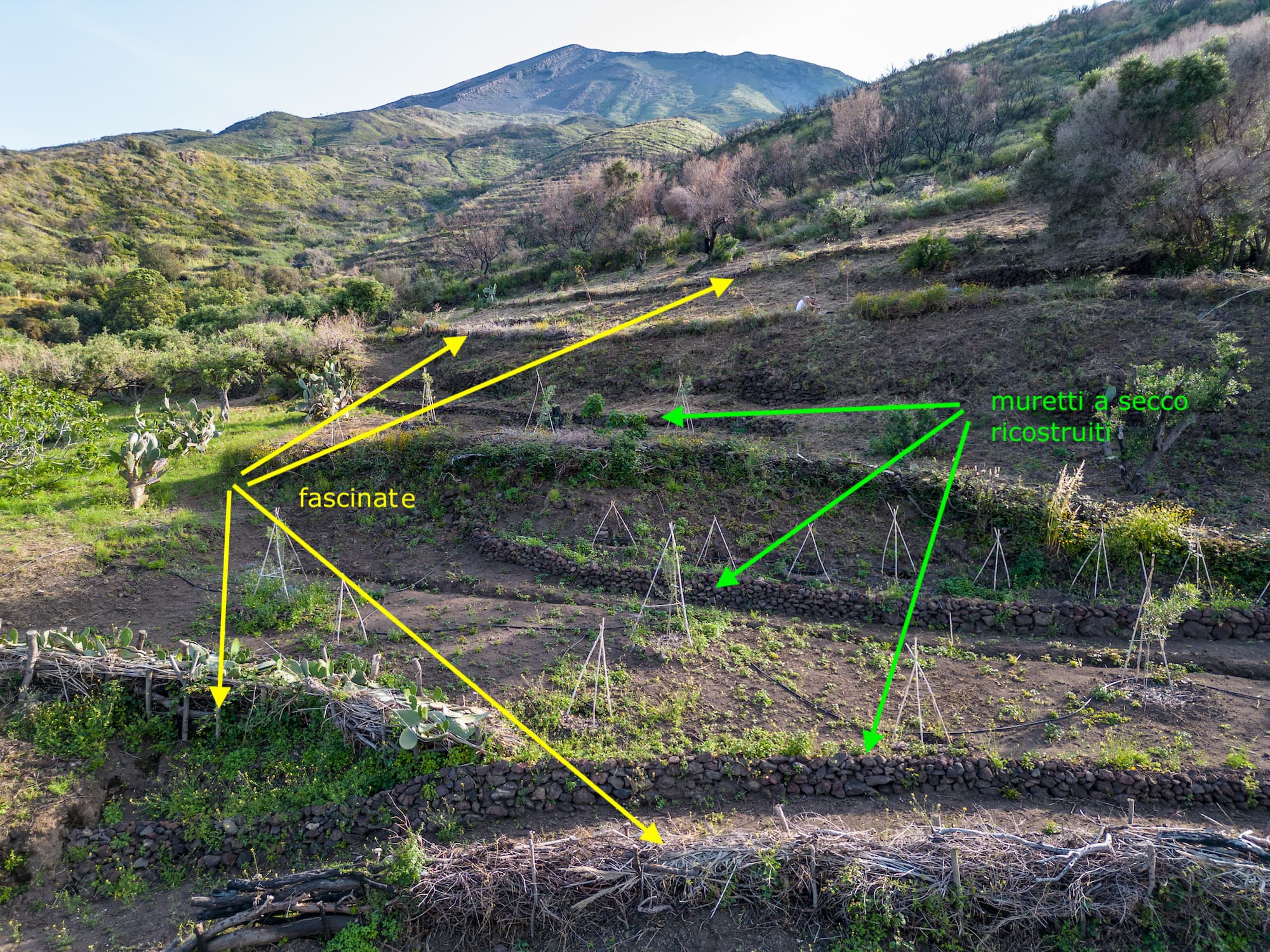

Where dry stone walls could not be fully restored, the group adopted a simplified traditional slope-stabilization method known as “fascinate,” or “palizzate,” also called the “beaver technique.” Bundles of pruning residues were fastened along slopes to slow water runoff.

Attiva Stromboli recovered many centuries-old olive trees and planted new Nocellara Messinese saplings, along with caper plants, creating a thriving intercropping system.

“With these structures in place, water no longer flows straight downhill but follows a zigzag path, releasing sediment and gradually leveling the terraces,” de Rosa explained.

The system promotes the development of microfauna, enhances soil fertility, and allows pruning residues to be reused on site. Maintenance mainly involves trimming vegetation when brambles begin to grow.

Attiva Stromboli recovered dry‑stone walls (indicated by the green arrows) and stabilized part of the slopes using the beaver technique, applying ‘fascinate’ (indicated by the yellow arrows).

“Once regulated, rainwater is no longer a threat but a resource that supports the growth of new olive trees,” de Rosa said.

Researchers confirmed the effectiveness of the work, noting that the agroforestry approach, combined with restored dry stone walls and the recovery of traditional ecological knowledge, reduces erosion risks, strengthens climate adaptation and restores agrobiodiversity while benefiting the local economy and tourism.

Attiva Stromboli also involved students from the island’s primary and secondary schools, engaging them in pruning, harvesting, and organizing training courses to introduce young people to olive oil production.

“Last year, we planted another 40 olive trees along the seafront as a public asset,” de Rosa said. “Olive trees deserve to once again be central to island life. Beyond their subsistence value, managing olive groves helps safeguard the entire ecosystem.”

“But this project does not end here,” he added. “This fragile ecosystem, exposed to natural and human pressures, requires constant care. Our hope is to secure further institutional support to continue this work.”

Share this article