Italian Bill Would Support Hobby Growers to Prevent Abandonment

A proposed bill in Italy aims to expand public support for olive growers with secondary occupations who maintain their orchards for self-consumption or sharing with family and friends. The bill seeks to encourage sustainable practices, restore abandoned groves, and recognize the important role of non-professional growers in safeguarding the country’s olive-growing heritage, ultimately aiming to combat abandonment and decline in olive oil production capacity. Additionally, a regional bill is being promoted to create a public Olive Observatory in Veneto to assess and support non-professional growers, with hopes for national approval and support from agricultural committees.

Public support for olive growing in Italy could soon be expanded to include more olive groves and growers than ever before.

According to a newly proposed bill, the government would acknowledge the work done by growers whose primary occupations lie elsewhere but still maintain and care for their olive orchards.

The olive oil produced from these groves is almost entirely used for self-consumption or shared within the grower’s close circle of family and friends.

See Also:Italy Unveils Plan to Revitalize Olive Oil SectorThe idea is to encourage growers to adopt sustainable practices and to help them recover and restore abandoned groves.

According to the National Agency for Services to the Agricultural Market (Ismea), at least three million families across the country are involved in self-production.

While there are no official figures on the quantities produced, it is estimated that between 30 and 37 percent of Italian olive oil production is destined for self-consumption.

“We are talking about small or medium-sized groves, which represent a secondary activity for many. Still, it is very important,” Alberto Bozza, regional councilor in Veneto and one of the promoters of the new bill, told Olive Oil Times.

“Their work is non-professional, but they take care of the environment, safeguard the land, promote biodiversity and help control pests such as the olive fruit fly,” he added.

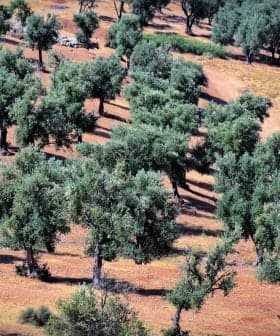

Most of these olive groves have been passed down through generations. Over time, however, the amount of work required to maintain them, combined with low yields and challenging climate conditions, has contributed to their abandonment.

This trend is widespread, particularly in hilly and mountainous areas.

“An abandoned olive grove harms the landscape and increases the risk of hydrogeological instability and wildfires,” Bozza said.

Such changes to the landscape are considered among the causes of the decline in Italy’s overall olive oil production capacity.

“The idea is to combat abandonment by recognizing new roles, including that of olive growers who are neither farmers nor agricultural entrepreneurs,” the proposed bill states. “These new roles should be considered guardians of the national olive-growing heritage.”

Last year, a new national law was introduced designating professional farmers and agricultural cooperatives as environmental custodians.

Olive cultivation in Italy covers approximately 1.1 million hectares, with nearly 620,000 producers and more than 4,300 olive oil mills.

In the last three years, the difficulties of remaining profitable have led more than 26,500 companies to cease operations.

“Even in this scenario, Italian olive oil is still considered the highest-quality product available worldwide,” Bozza said.

According to the bill’s promoters, the superior quality of Italian olive oil depends on the country’s wide variety of olive tree cultivars, unique climate conditions and traditional production processes.

However, many family growers are not eligible for public support and have limited access to technological innovations despite contributing to Italy’s olive biodiversity.

Current laws exempt self-producing growers from the strict regulations applied to professional producers, including requirements for traceability and the registration of production volumes in the National Agricultural Information System (SIAN).

Growers are classified as non-professional as long as their annual olive oil production does not exceed 350 kilograms, and their product is not sold.

“In this context, a crucial step is to have a clear picture of the situation,” Bozza said, stressing the lack of reliable official data.

For this reason, Bozza and his colleagues are also promoting a regional bill calling for creating a public Olive Observatory in Veneto. “This is a critical step that other Italian regions could easily adopt,” he said.

According to Bozza, the observatory would allow the region to examine, verify and monitor the condition of its olive-growing areas. The goal is to carry out a precise census to classify all olive-growing lands and assess the health of each cultivated area.

“This census will help regional institutions evaluate how to support non-professional growers,” Bozza added, suggesting that additional resources could be made available through regional, national and European programs.

Several associations in the farming and olive sectors have already expressed support for the new legislation.

According to Tommaso Loiodice, president of the National Union of Olive Oil Producers (Unapol), the bill should be supported to help prevent the abandonment of olive groves.

“However, it is important not to confuse this type of olive growing, which I would call hobbyist and which in most cases produces oil for family consumption, with commercial olive growing that supplies the market,” Loiodice said.

“In my view, the proposed law should encourage cooperation and aggregation among these small producers, with a long-term vision aimed at creating more structured and profitable businesses,” he added.

Bozza hopes the approval of the observatory will come from the Veneto regional council by this summer.

“As for the national bill, it will be assigned to the relevant parliamentary committee,” he said. “At that point, I will work to raise awareness among national parliament members, especially those on the agricultural committees, to try to speed up the process if they believe the proposal aligns with national agricultural policy priorities.”