EU Lawmakers Delay Mercosur Trade Deal After Narrow Vote

The European Parliament voted to delay the EU-Mercosur free trade agreement, seeking a legal opinion from the European Court of Justice, potentially delaying the deal for up to two years. The agreement, which would create the world’s largest free trade area and eliminate tariffs on 99% of goods, has faced opposition from European farmers and lawmakers concerned about competition and trade barriers.

Less than a week after the European Union’s free trade agreement with Mercosur was signed in Paraguay, the European Parliament voted to delay the deal.

The agreement had already received approval from the European Council, composed of the 27 foreign ministers of the member states, and lawmakers were widely expected to follow suit.

Instead, members of the European Parliament from the far right joined their far-left and Green party counterparts, voting 334 to 324, with 11 abstentions, to seek a legal opinion from the European Court of Justice.

The request could delay the agreement for up to two years. However, members of the European Parliament’s trade committee said lawmakers may allow parts of the deal to be implemented while the court conducts its review.

Lawmakers asked the court to examine a clause that would allow Mercosur members — Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay — to reimpose tariffs on European goods if their agricultural exports are restricted by future European policies.

If approved by the European Parliament and ratified by the four South American countries, the EU – Mercosur agreement would create the world’s largest free trade area, covering about 700 million people and eliminating tariffs on 99 percent of goods.

European beef, poultry, dairy, fruit and grain farmers have long argued that they cannot compete with the lower production costs of producers in Argentina and Brazil.

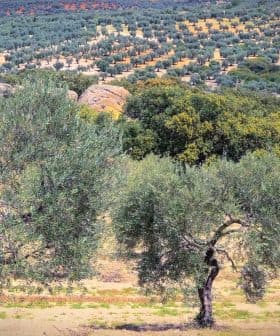

While European olive oil producers have welcomed the deal, table olive producers have warned that its structure places them at a disadvantage.

The agreement requires European countries to remove tariffs immediately, while South American countries would phase out tariffs on certain goods, including table olives and olive oil, over a 15-year period.

Hundreds of farmers gathered outside the European Parliament in Strasbourg, France, ahead of the vote to protest the agreement.

Uruguay’s deputy foreign minister, Valeria Csukasi, told local media that it would be unimaginable for the European Parliament to approve the deal while farmers were actively protesting. Even so, Uruguay’s foreign ministry expects the agreement to clear the review despite what it described as a temporary “stumbling block.”

Meanwhile, the governments of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay are continuing with domestic approval processes in their respective legislatures.

Some European lawmakers remain skeptical about the deal’s future. A prominent member of the center-left Socialists and Democrats group described the vote as a “stalling tactic” aimed at undermining the agreement.

Within the olive oil sector, some stakeholders have suggested that opponents of the deal are showing greater coordination and urgency than supporters seeking to see it ratified.

For his part, the chief executive of Argentina Olive Group, the Southern Hemisphere’s largest olive oil producer and exporter, argued that trade barriers ultimately benefit no one.

“Protectionism is not good for productivity,” Frankie Gobbee told Olive Oil Times. “The more freedom there is, the more trade exists in the world and the greater the chances for people to live better. That’s a universal rule: when the world closes itself off, people live worse.”