Climate Pressures Drive Search for New Olive Varieties Suited to Modern Groves

Climate change and labor shortages are top concerns for olive oil producers worldwide, leading researchers to focus on developing new olive varieties suited to super-high-density hedgerow systems. AGR by De Prado has delivered over eight million olive tree seedlings, with varieties like Lecciana, I‑15, and Sikitita showing promise for increased productivity, drought tolerance, and unique flavor profiles, while also adapting well to organic production and mechanical harvesting.

Each year, climate change and labor shortages rank among the top concerns of olive oil producers worldwide.

As many of the world’s most productive olive-growing regions become hotter and drier and hiring sufficient labor remains a perennial challenge, researchers and nurseries are increasingly focused on developing new olive varieties to meet these pressures.

For each grower, in each region, depending on their goals, there is a most suitable variety because all of them have their strengths and weaknesses.

Andalusia-based AGR by De Prado has focused on varieties suited to super-high-density hedgerow systems, offering either more distinct flavor profiles or improved tolerance to heat and drought.

The nursery and agricultural services division of olive oil producer De Prado has delivered more than eight million olive tree seedlings from its two nurseries in Spain and Portugal. Most of these have been Arbequina, Arbosana, Lecciana, Coriana, I‑15, Sikitita, Sikitita‑2, Cacereña and Hojiblanca.

“Until about eight or ten years ago, the only varieties suitable for modern super-intensive hedgerow systems were Arbequina and Arbosana,” Manuel López, AGR by De Prado’s director in Spain, told Olive Oil Times.

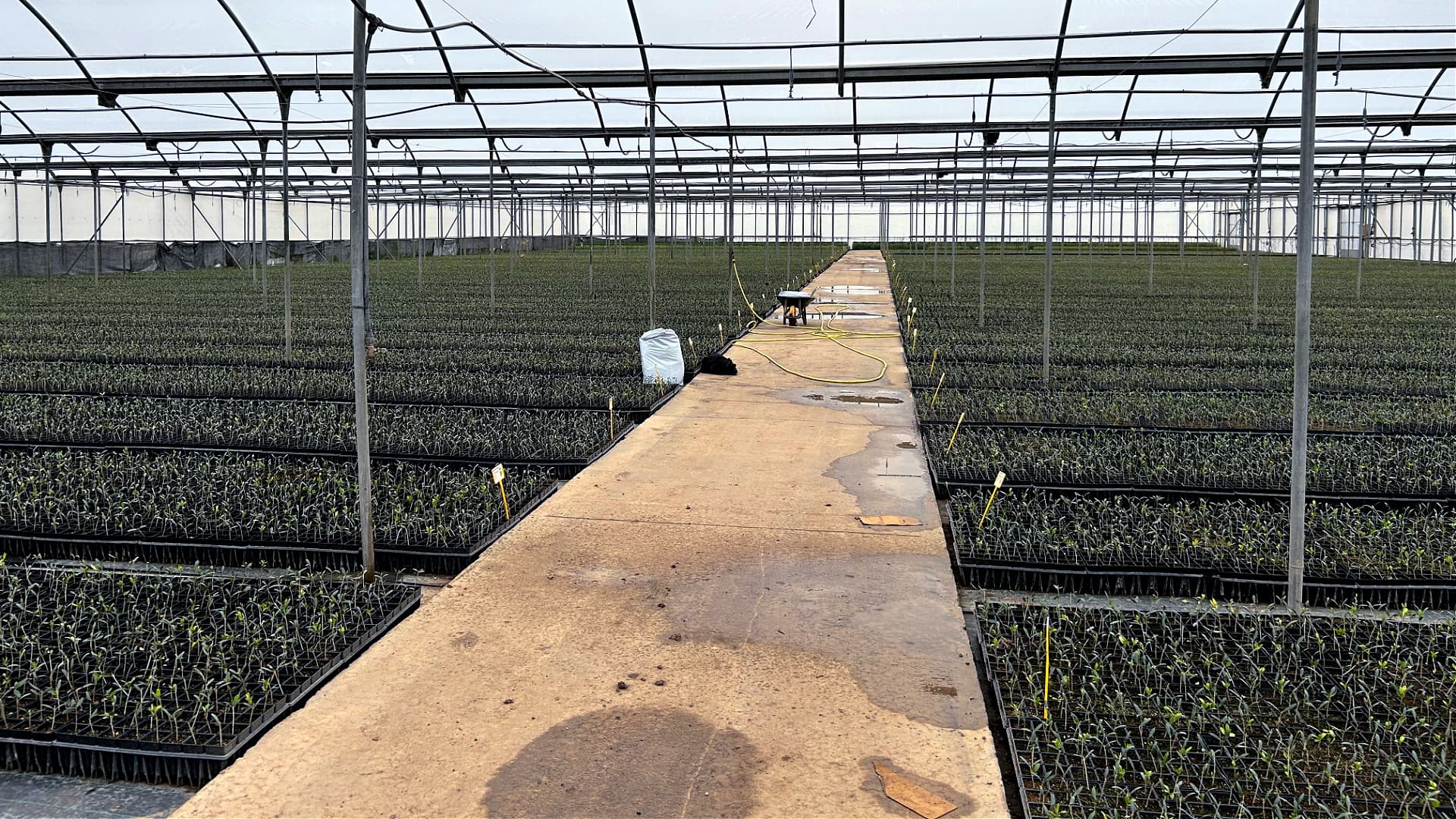

López said the company frequently sells out of its newly-developed varieties indicating their rising popularity among farmers. (Photo: AGR by De Prado)

However, he said that “ambitious genetic improvement programs” launched in the 1990s at the University of Córdoba in Andalusia and the University of Bari in Puglia aimed to boost productivity and increase tolerance to abiotic stresses such as drought and cold.

Over the past three decades, this work has produced more than 1,000 new varieties through targeted crosses using parent plants with specific desired traits. Several of these are now emerging as alternatives to Arbequina and Arbosana.

“Now the challenge is to properly process all the information provided by the trials to separate those that offer real value from those that offer nothing new,” López said.

Unlike annual crops such as corn, where performance can be assessed after a single season, testing new olive varieties can take up to a decade, López explained.

“With woody crops like olives or almonds, you need three years just to see the first production and then at least three or four more years to confirm reliability and consistency,” he said.

Trials must also be replicated across different environments, López added, including areas with varying water availability, temperatures and soil types, to determine where each variety performs best.

While López does not believe a perfect olive variety exists, he said the eight main varieties currently propagated by AGR by De Prado have shown the strongest demand.

López sees super-high-density olive groves playing an increasingly important role in global olive oil production as finding enough workers to harvest traditional groves becomes ever-more challenging. (Photo: AGR by De Prado)

“These eight are the ones that, after evaluation, we see as having the most potential right now,” he said. “There are many others available, but there is still insufficient data.”

According to López, the varieties being planted today are proving to be profitable, productive and consistent, while also contributing distinctive characteristics to the resulting oils.

Although there is no clear evidence that any of the new varieties outperform Arbequina and Arbosana in terms of yield per hectare, López said there are signs that the market is increasingly interested in more robust flavor profiles.

“Some mills are starting to say there is already too much Arbequina,” he said, noting concerns about oil stability. “Other varieties maintain good stability through July, August or even September, which is interesting for marketers.”

López added that hedgerow systems will need to produce oils with a broader range of chemical and organoleptic profiles, including bitterness and spiciness similar to Picual or Hojiblanca.

In addition to stronger flavors, López said many newer varieties show improved tolerance to water stress and cold and adapt more effectively to organic production.

Field trials have shown that Sikitita 1, I‑15 and Lecciana are more drought-tolerant than Arbequina or Arbosana, contributing to their rapid adoption.

“That’s why these varieties are now being planted heavily,” López said. “They are the first to sell out in nurseries.”

Lecciana has also performed well in organic systems and colder areas, while Sikitita 1 has shown strong potential in dry-farmed orchards.

Sikitita 2 has proven highly productive and easier to prune due to uniform branching, helping reduce rising pruning costs.

As a result, López said many growers are diversifying plantings to spread risk and extend milling seasons by combining varieties with different flowering and ripening times.

Despite their advantages, López cautioned that each variety also has weaknesses.

Lecciana, for example, can produce excessive woody growth under irrigation, increasing pruning demands, while I‑15 requires careful pruning to avoid damage during mechanical harvesting.

“For each grower and each region, there is a most suitable variety,” López said. “There is no perfect solution for everything.”

AGR by De Prado is currently evaluating additional varieties that could ripen earlier in October, allowing mills to begin production several weeks sooner.

López said rising production costs, which can be roughly three times higher per hectare in traditional groves than in super-high-density systems, are accelerating the shift away from traditional Picual orchards on steep terrain.

“Picual is a spectacular variety that produces excellent oil, but it cannot be planted in hedgerows,” he said. “Because of labor constraints, many producers are transitioning to super-intensive systems.”

He expects modern orchards to continue expanding wherever terrain allows mechanization, while traditional groves persist on marginal land.

Like former Deoleo chief executive Ignacio Silva, López believes traditional varieties will remain essential in niche markets.

However, he noted that consumers outside producer countries often prefer milder oils, a trend he does not expect to change soon.

“From our exports to more than 25 countries, we see that American and Asian consumers generally prefer milder oils,” López said.

He concluded that the key lies in blending oils to match consumer preferences, using a range of varieties to create balanced profiles tailored to different markets.