Q&A with Piero Gonnelli, Frantoio Santa Tea

Piero Gonnelli, director of the Frantoio Santa Tea, discusses his family’s 400-year-old olive oil business, highlighting changes in production methods over time and the quality of their product. Gonnelli emphasizes the importance of machinery, product quality, and innovation in setting Gonnelli olive oil apart from others, sharing his dedication to the work and tradition of producing olive oil.

In the second of our two-part series, Lara Camozzo sits down with Piero Gonnelli, director of the Frantoio Santa Tea, and head of a family olive oil business that has spanned more than 400 years. Mr. Gonnelli’s answers are translated from Italian.

When did the story of Gonnelli olive oil begin?

“The mill was built in 1426, and my family bought this place in 1585. I grew up here, and began working with the olives when I was a young boy — I was fourteen years old. The world was a completely different place.” He points out the window towards his land and says, “All of the land in this region was made up of gardens and olives trees, and there still existed in Italy La Mezzadria.” This term stands for an agricultural agreement that existed betweenthe proprietor of the land, and the farmer who lived on and worked the land with his family. “It was called la mezzadria because they divided the produce in half, mezza — half to the proprietor, and half to the farmer and his family.”

Can you recount some of your memories from this time?

“I remember from when I was young, the fatigue of these people who worked the land. First, they’d work the soil, and in November they’d begin harvesting the olives. However, since the harvests were done completely by hand, it took quite a long time — until February or March, when the ground had frozen. So these people would harvest the olives first from the trees, and then from the ground — all by hand — during a cold that you can’t imagine. It was a terrible job. Then, with industrialization, the world changed; we no longer harvest the olives that have fallen on the ground, because it isn’t convenient.”

What has changed today with respect to the past?

“Now, we harvest the olives after much anticipation. When you wait until January or February the olives have become too mature and have fallen to the ground. It’s the same thing as if you were to take a piece of fruit from the ground — it’s not good anymore. And so the quality of the product that they obtained in the past was not like what we are capable of producing today. Today we take the olives before they are ripe, because it is said that the optimal time period for the harvest is fifteen days — but it’s not possible to harvest everything in fifteen days. So we have to be shrewd; some types of olives, like the frantoio, are best harvested very early, when they are not yet ripe, in order to produce a superior quality of oil. This alone was a big change, but what truly changed the quality of the product was a new system for working with the olives — new machinery. With these new machines we’re now able to harvest the olives, press them immediately, and get the oil in the very same evening. So there’s no fermentation, the acidity is extremely low, and the level of quality is extremely high. With the old system, the press, this wasn’t possible, because we couldn’t press the olives just after harvesting them — the olives were left to ferment, to get soft, before we could press them. The first centrifugal press was introduced in 1962, and Santa Tea was the first mill in the world to use this new system. In 2002 we were also the first in the world to use an oxygen free production system; by adding nitrogen to the tubes and tanks during production and storage, we decreased the oxidation index by 50% and increased the shelf life of our olive oil to two years after bottling.”

What sets Gonnelli olive oil apart?

“One characteristic that sets us apart is our machinery. I designed all of our machines, except for the centrifugal press which is made by Alfa Laval. All of the other machines are made here at Santa Tea. I’ve been involved with this activity for forty years — making modifications to the machines and innovating various new types. We’re always geared towards bettering the quality of the final product. In addition, the way we manage our factory, our selection of products, and our capacity to select good olives, which is important because the consumer should know what they are buying — these are all aspects that set us apart from the others.”

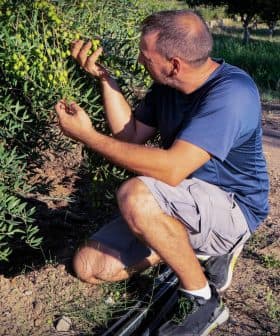

Piero Gonnelli (third from left) observes the new centrifugal machine.

How did you become involved in the design of your machines?

“When I was 14 years old, we started using the new centrifugal press for the first time. This Swedish company, Alfa Laval, sent all of their technicians in order to put this new system into place. I spent my whole Christmas vacation in the oil mill, learning about the world of mechanics alongside these technicians. I became passionate for constructing my own machines, so at 18 years old I began working with my father who ran the other agricultural side of the business — the vineyards, the cantina, etc. But, what I enjoyed most were the mechanics of the olive oil mill, because I had the opportunity to develop something, to think and create something new. So at 18, my father left me in charge of the mill.”

What changes, if any, did you make when you took charge of the olive oil production?

“I wanted to spread the knowledge of our product, so I took it around the world to fairs and conventions in search of buyers. It’s pointless to make great olive oil if no one can find it and taste it. It wasn’t easy, because clearly an oil like this has a higher price due to the methods we use and also because the earth in the Chianti region is difficult to cultivate. One of our trees makes 1.5 kilos of olive oil. In Maremma, a southern region of Tuscany, one tree can make 6 kilos of oil. In Puglia, one tree makes 20 kilos, and in Spain, using the super intensive system, every hectare produces 4000 liters of olive oil — an enormous production. One hectare in Chianti makes 400 kilos, but the quality of the product is different, and our prices reflect that. When I started with the company in the 1960s, we were selling next to nothing — maybe 1000 to 2000 bottles. Now, we sell 6 to 700,000 bottles of oil every year, and we’re growing.”

What are your thoughts on the “New World” extra virgin olive oils?

“Well, first I want to make clear that all oil, if made well, is a special product that is good for your health. The best and the worst depends on us, on our own personal taste — it’s subjective. Obviously, if a person grows up in a certain place, from a young age they will become accustomed to a particular taste, and they will think that the product from that place is the best in the world. For me, Spanish oil, I can’t eat it — it makes me nauseous — but the Spanish eat it, and they like it — it’s absolutely subjective. In terms of production, our methods are different, and the olive varieties themselves are different. Even if the same methods are used, if you change the olives, you change the product — like all things. Like with fishing; fish are all fish, but one has a different flavor from another. It’s the same with olives; every product has certain characteristics that are reflected in the flavor.”

What of the differences in methods of production, is one better than the other?

“At the moment, we are experimenting with new harvest methods, but we are not convinced at all by the machines that are used in Australia and California. These machines shake the trees which, in our opinion, damages the plants and leaves the best olives still attached to the tree. For example, there are parasites that sometimes infect the olives — clearly, we don’t want to use these olives, because they would ruin the product. If a plant has 5% infected olives, and I use one of these machines to harvest, these weak olives will all fall to the ground while 20% of the good, strong, healthy olives will remain attached to the plant.These machines deteriorate the quality of the product — this is why I don’t love them. There is also a super intensive system, in which the olive trees are planted like vineyards, which allows a machine to pass through the rows taking the olives like bunches of grapes. I don’t like this method either because it bangs the fruit around and damages the plants. At Santa Tea we use a hand rake that grabs a single branch at a time and vibrates until the olives fall into nets covering the ground. This system doesn’t damage the fruit or plants, and it allows us to harvest all of the olives; it’s a step ahead of harvesting by hand, but it’s very expensive. In the future we must find different alternatives for harvesting by hand, we must evolve.”

How old are the trees on your properties?

“In 1985 we had a big frost that destroyed at least 50% of our trees. Many of those trees were 100, 300, even 400 years old. After the frost, only 5 or 6 trees remained that were 150 years old. Today we have around 22,000 trees in the provinces of Florence and Siena, most of which are 24 — 25 years old.”

What does olive oil mean to you?

“It means everything. It means tradition, it means family, it means work. I’ve dedicated my life to this work — it’s a work that I love, so I am a lucky man.”

Did you ever want to follow another path in life?

“My life has always been tied to this work, but I’ve done other things. I worked for ten years producing construction materials, tiles, etc. I also constructed houses. But my work with the olive oil is my heart — my heart is here — the rest is business.”