Making Olive Oil in France the Ancestral Way

Millers in the rural town of Coudoux, France, are perpetuating the ancestral way of producing olive oil to offer a traditional product that tastes the same as it did a century ago.

Millers in Coudoux, France are dedicated to producing high-quality, traditional olive oil using ancestral methods, as showcased in a report by TF1. The process involves grinding green and black olives together with their pits, pressing the paste in scourtins, and allowing the oil to naturally filter for seven weeks, resulting in a unique and valuable product that retains the original taste of olives.

Millers in the rural town of Coudoux, France, are perpetuating the ancestral way of producing olive oil and are adamant about doing so in order to be able to offer a high-quality, traditional product.

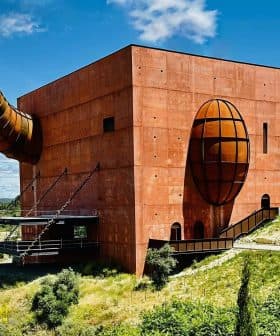

A report that aired on TF1 takes us through the ancestral way of producing olive oil in Southern France. Millers from Coudoux, Bouches-du-Rhone (located in the Provence region) are among the last ones who still produce olive oil the way it was made many, many years ago.

The process starts with the control of the olives brought by the nearby growers. The olives are weighed and the miller checks their sanitary qualities. Then comes a period of rest for the olives. The miller takes them to the last floor of his century-old tenement; the olives will stay there for four to five days until they “mature” to a satisfying level. This period of idleness is a staple of an ancestral way of making olive oil in Provence.

Soon the olives that are stocked on the last floor of the mill start to fill the space. Scents of thyme, almond, and wood fill the space.

Green and black olives are mixed, which will eventually allow the miller to yield his distinctive olive oil. The olives are ground with two, six-ton granite wheels.

“Way back, we used horses and donkeys to make the grinder spin around. Nowadays we use an electric engine but the process remains essentially the same,” noted the miller. “Olives that are stocked in the building’s last floor come down through a tunnel and land in the grinder, where they are crushed.”

The mill had to undergo structural changes to meet the European Union standards, but the recipe for making olive oil has remained the same. The olives, which are ground with their pits, become a paste that is spilled onto scourtins — sheets that used to be made of coconut fibers.

The scourtins of olive paste are stacked on top of each other and put in a pressing machine that generates 400 bars of pressure. The golden liquid eventually comes out and flows down into impressive vats.

Hyacinthe, a mill worker, is assigned with the task of collecting the fresh oil; she is maneuvering a rather enormous tool known as a feuille, a long metal pipe which ends with a stove-like hollow. “This is a first decantation which ensures water stays on the bottom of the vat. The oil, which is lighter, ascends towards the top of the vat,” she said, while gathering it with her quaint feuille. “We want to make sure no water is present in our oil,” added a seemingly proud Hyacinthe.

The oil is then put in huge cylinders in which it will rest for seven weeks in order to be filtered naturally. That is what makes Coudoux’s olive oil so valuable, the miller said, pointing at the precious liquid: “What makes our oil so green is the ancestral way we produce it. Why? Because the oil has remained in contact with all the elements that form olives: skin and pulp, for an extended period of time.”

The product is now finished. The miller in his 100-year-old mill considers the traditional way crucial if one truly wishes to experience the olive oil’s “original taste.” The miller, along with his workers, can be seen at the end of the footage proudly drinking the oil they made.