21.9K reads

21.9K readsWorld

A Forgotten Treasure: Making Oil from Wild Olives

Feral olive trees, with their small fruits often regarded as not profitable, have been neglected for centuries, but some producers are now starting to harvest them for their unique flavor and high antioxidant content. The oil from these wild olive trees, known as acebuches, is being produced in various regions of Spain, offering a different taste and composition compared to oil from cultivated olives.

Ancient Greeks used their branches to weave their Olympic wreaths and Roman emperors are said to have kept aside the oil from its fruits for their personal use. But for most of the centuries, feral olive trees were just forgotten in the bushes.

I always say it is like giving a bite to the mountain. It tastes like wild Nature.

These small-leafed, poor relatives of the cultivated olive trees, were often left aside, its tiny fruits regarded as not profitable enough to be harvested. This happens even nowadays. An average of 4 to 6kg of olives are needed to produce a liter of oil from commercial varieties, whereas for wild olive trees this amount increases to 15 – 20kg.

Thus, cultivated olive trees, with a much higher yield, dominate olive oil production. However, some producers are starting to turn their eyes to this kind of widely neglected olive tree.

“Of course, there is great quality olive oil from cultivated olives. We also have it. But the oil from wild olive trees has a particular flavor, a different taste. When you take it to a tasting panel, professional tasters don’t know how to describe it,” says Francisco Villanueva, co-founder of Aceite Mudéjar, a family-run company that produces this particular kind of oil.

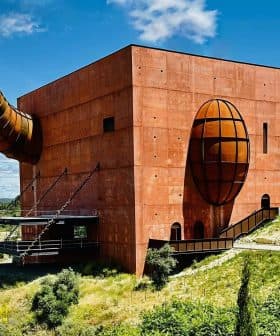

We meet him and his partner, Fernando Martín, at the doors of their olive oil mill in Monda, some 40km southwest of Málaga, in Andalusia.

“When someone asks me how it tastes like, I always say it is like giving a bite to the mountain. It tastes as wild Nature,” he tells Olive Oil Times.

But the flavor is not the only reason that is making oil of feral olive trees commercially viable.

“There is a fundamental difference in terms of organoleptic characteristics, but its composition is different as well. It has, of course, the same fatty acids, but regarding phenolic compounds and vitamin E, it has a much bigger share of them. When we send a sample to specialized labs, they ask us where we got this oil from. They find this unusual amount of antioxidants,” says Villanueva, who is also a doctor.

Wild olives (Pablo Esparza)

Those characteristics have made the oil an appreciated cosmetic and medicinal compound.

In Spanish, feral olive trees are called acebuches and their fruits are known as “acebuchinas.”

Both words have Arabic and Berber origins, a legacy of the century’s long Moorish past of the region.

Villanueva and his partner Fernando Martín began to produce acebuche oil just a few years ago when they started harvesting the acebuchinas growing on the green slopes of the Sierra de las Nieves (literally “range of the snows”).

This UNESCO biosphere reserve, halfway between Málaga and Marbella, seems ages away from the hustle and bustle of the tourist centers of the Costal del Sol. It is an ideal territory for “acebuches.”

But oils from feral olive trees are also being produced elsewhere, from Cádiz, at the Southernmost corner of Spain, to Jaén, in central Andalusia, and the Mediterranean island of Mallorca, where acebuches are called “ullastres” in Catalan language.

“There are many kinds of acebuches. Some of them are sons of cultivated varieties. Their fruits are a bit more similar to those of cultivated varieties. Others are grandsons of great-grandsons of acebuches. Those are the truly rich ones to get ‘acebuchina’ oil from them,” explains Villanueva.

Size is the main external difference between cultivated olives and feral ones. “Acebuchinas” are much smaller and they have a higher proportion of olive pit.

The color of their pulps is also different. While cultivated olives have a whitish purple flesh, acebuchinas have an intense blood-like juice.

The result is a completely diverse type of oil. One that has perhaps been forgotten for too long. As Villanueva puts it: “If Roman emperors used it, why not us?.”