Millions of Birds Killed by Nighttime Harvesting in Mediterranean

Upwards of 2.5 million birds are killed each harvest season in Spain, Italy, France and Portugal.

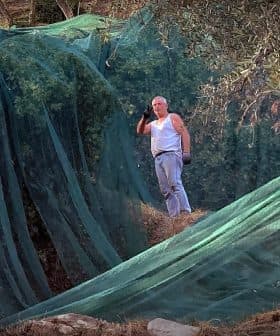

Photo courtesy of Junta de Andalucia

Photo courtesy of Junta de Andalucia 6.9K reads

6.9K readsMillions of birds are killed each olive harvesting season in the Mediterranean basin, with 2.6 million birds killed in Andalusia alone. The birds, many of which are legally protected, are sucked out of trees at night by super-intensive harvesting machines, leading to calls for a ban on nighttime harvesting to prevent further bird deaths.

New research from Portugal’s Institute for Nature Conservation and Forests has found that millions of birds are killed each olive harvesting season in the Mediterranean basin.

The songbirds, many of which migrate from northern and central Europe to winter in North Africa, frequently stop in southern Spain, France, Portugal and Italy, to rest while they are traveling and are sucked out of the trees at night by super-intensive harvesting machines.

A good part of these birds are sold by the operators of the harvesters or the cooperatives to the rural hotel industry for consumption. This practice is illegal.

The group estimates that in Andalusia, 2.6 million birds are killed each year during the harvest, while in Portugal an additional 96,000 birds die. In France and Italy, similar practices are used, but statistics on bird deaths during the harvest season are not kept.

See Also:Bans on Night Harvesting Have Alleviated Threat to Migratory BirdsBright lights from the super-intensive harvesting machine disorient the birds, which are not nocturnal, and prevent them from escaping when the nighttime harvesting begins. Olives are frequently harvested at night as the cooler temperatures preserve their aromatic flavors.

“Suction olive harvesting at night kills these legally protected birds on a catastrophic scale as they rest in the bushes,” researchers Luis da Silva and Vanessa Mata wrote in an open letter to the journal Nature.

However, during the day, the same practices are not nearly as dangerous for the birds, which are able to escape when they hear the machines coming.

“The machinery is perfectly fine if used during the day, as birds are able to see and escape while they are operating,” Mata told British news organization, the Independent.

Many of the birds affected by nocturnal super-intensive harvesting are classified as “resting species” by the European Union Bird Directive, which entitles them to special protections.

“They should not be subject to disturbance in the rest period,” Domingos Leitão, from Portuguese Society for the Study of Birds, said. “If the birds in one row of olive trees are frightened, they fly to another; the Birds Directive says that they should not be disturbed during the rest period.”

Increased awareness of the situation has led the Junta de Andalucia, the region’s local government, to investigate the problem in an effort to try and legislate a solution before the next olive harvest begins in October.

During the investigation the junta found that many olive producers were taking the dead birds and selling them to local hotels as “pajarito frito” or fried bird, a practice that is highly illegal, especially when these fried birds include endangered species.

“According to both the Civil Guard and the [Ministry of the Environment], a good part of these birds are sold by the operators of the harvesters or the cooperatives to the rural hotel industry for consumption,” the junta said. “This practice is illegal and highly condemned by the Ministry of Health due to a lack of sufficient health guarantees for public health.”

No charges have yet been brought against any growers or hotels. The Junta de Andalucia has so far concluded that the best way forward is to ban super-intensive harvesting practices at night.

“The best option to end the problem is that super-intensive harvesting of olive groves is banned during nighttime hours, which would prevent migratory birds from being caught by the machine’s spotlights,” the junta said.

However, no legislative action has yet been taken to ban the practice and advocates expect another “massacre” to come next harvest season if nothing is done.

“When negative impacts like these are detected, the authorities must act swiftly and accordingly,” Nuno Sequeira, head of Portuguese environmental organization Quercus, said. “We are talking about hundreds of thousands of dead birds.”

So far the Portuguese government has acknowledged the issue, but has yet to take action. The issue has been largely ignored in both France and Italy.

“Local governments and local, national and international communities urgently need to assess the impact of the practice and take steps to end it,” da Silva and Mata said.