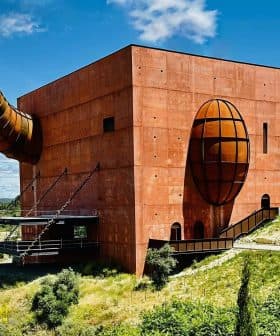

Tunisia: Window on a Traditional Olive World

There are scant funds to assist Tunisia's rural farmers' transition to a more efficient, high-quality production. Some locals say that's just fine with them, while others look to a more prosperous future,

Photo: Cain Burdeau for Olive Oil Times

Photo: Cain Burdeau for Olive Oil TimesTraditional olive oil production in Tunisia is still largely a rural activity, evoking a bygone era, even as the country seeks to expand its high-quality olive oil production through modernization. The rural population in Tunisia lives in poverty, leading to traditional and simple methods of olive oil production, while also facing challenges such as lack of resources for modernization and resistance from entrenched interests.

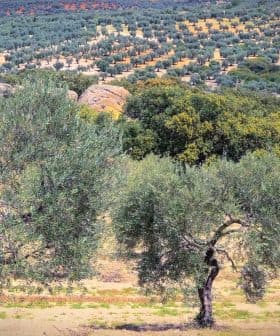

Picking olives – even well into the spring – with bare hands and fingers threaded with goat horns. Collecting bags lying in fields full of olives and tree cuttings by cart and donkey. Making oil in mills where grinding stones crush olives and the floors are busy with crews of workers covered in olive juice.

In 30, 40 years time I would be quite sad frankly if we ended up with an industrialized production style.

These are sights, sounds and smells mostly long gone from Europe, where olive oil production has increasingly become mechanized and modernized.

But in Tunisia, things are different – olive oil making is still largely a rural activity evoking a bygone era.

This is viewed both as an obstacle and a treasure for a nation seeking to expand its production of high-quality olive oil through modernization and an expansion of olive plantations while it also deals with deep rural poverty, entrenched business interests and political and economic instability.

Tunisia’s rural population lives in a state of poverty – and this fact helps explain why olive oil production is so traditional and simple. Yet the sheer size of its production (180,000 tons this year) and its ambitions as a major exporter set Tunisia apart.

“The problem isn’t a lack of technical knowledge in Tunisia,” said Tiziano Caruso, an agrarian and olive specialist at the University of Palermo in Italy, “but the lack of financial resources to spread” modernization.

The World Bank says Tunisia’s rural population lives in a state nearing extreme poverty. Rural workers often earn about $6 a day, or often much less. Average per capita daily income in rural Tunisia is $1.60, according to World Bank figures.

This explains why the vast majority of exports are in bulk, sent off in ships to richer countries in need of olive oil; why a drive through the countryside during the springtime finds people still picking olives that are black and overripe; why productivity can fluctuate so radically from year to year and why yields are much lower than European competitors.

There are other problems too. Irrigation is scarce. Many plantations are young and there is lack of know-how among many farmers, Tunisian oil producers said. And since the 2011 democratic revolution that ended a dictatorship, producers said they have been hit by a dwindling rural workforce that in turn has driven up labor costs.

Meanwhile, many farmers and producers complain that entrenched interests at the government and private levels are also impeding change and progress.

At the end of January in a small town called Bir Salah in the olive-tree dotted plains near Sfax, the olive harvest was in motion.

A half-dozen people worked on one large tree. Men standing on the ground and on heavy wooden ladders beat drupe-laden branches with sticks to get the olives off. A stooped woman in a head-scarf swept olives on collection nets into piles, using as a broom a handful of olive branches.

Photo: Cain Burdeau for Olive Oil Times

“It’s the job of the zaytun (olive tree in Arabic),” said Amine Mhimda, a 20-year-old student helping his family during a school holiday. He spoke in basic English. “Friends and family (do the work.) It’s the job of my family.”

The tree they were working on wasn’t theirs but instead one they had rented to pick, a common practice among Tunisian farmers.

Mhimda said picking machines are too expensive for his family.

Similar scenes are found throughout Tunisia, where families spend months slowly picking olives from the nation’s millions of trees. They stop at mid-day to eat and make pots of tea on fires.

The olives are poured into bags and packed to olive mills, often on the backs of pickup trucks streaked in olive juice.

Photo: Cain Burdeau for Olive Oil Times

Often olives end up in places like a mill in Sfax owned by Hamed Kamoun. His family has been in the olive business since the late 1800s.

It’s a traditional mill. On a recent morning, workers were busy inside working the presses, the grinding stones, pouring oil bucket-by-bucket into decantation vats. Overhead, a big belt whirred as it spun on a lineshaft driving the rotating grinding stones. The smell of crushed olives was intense and pleasant. The floor was covered in black pulp and oil. Olive presses dripped with dark juice.

“My production is specific and only for here,” Kamoun said, speaking through a translator. All the oil he makes, he said, is consumed in Tunisia.

Before the break of dawn during the harvest period, Kamoun has a buyer at an auction market where farmers sell their olives to mills. He gets large quantities of olives from this market, he said.

Many in Tunisia’s olive business, though, say these traditional methods of harvesting and milling are holding the nation back.

For instance, many farmers wait to pick olives until they are deep black and more mature in the hope of getting more oil out of them. But this goes against best-practices for obtaining the best extra virgin olive oil, which generally occurs when olives are turning from green to black, a phase known as invaiatura.

Photo: Cain Burdeau for Olive Oil Times

“People have small knowledge about olives, so they think if we pick olives now (in January and later) we get more olive oil — it is right, but it is wrong,” said Rafik Ben Jeddou, an oil producer.

Habib Douss, an oil exporter and chemist, said many farmers believe the olive tree is a sacred plant.

“There’s a lot of mythology in olive oil,” he said. “As far as the olive tree is concerned, Tunisians feel it is a blessed tree. Nothing from the olive tree can be discarded and so if there are olives late in the season, it’s part of the bounty. If they pick it in May, to them it is blessed.”

Douss added: “When I worked for Proctor and Gamble (in the United States) we talked about ‘opportunities for improvement,’ or OFIs. In Tunisia, you could write encyclopedias of OFIs.”

Imed Ghodhbeni, the manager of a tasting and analysis laboratory for the CHO Group, a major Tunisian exporter, said many Tunisians dislike the taste of extra virgin olive oil.

“Some people actually like this,” he said about oil he would consider lampante. “People will keep the olives a long time to ferment to get this kind of oil.”

Photo: Cain Burdeau for Olive Oil Times

In southern Tunisia, for example, it is common for Berbers to keep olives in caves, allowing them to ferment, and to press olives when they need them, he said. “They are proud of their oil and offer it to guests,” Ghodhbeni said.

Tunisia is not unique in this. In southern Italy, for example, it was customary to let olives ferment too until more recent times.

“In Italy, especially in the South, the olive sector … has made giant steps forward only in the last 20 years,” Caruso said, referring specifically to oil extraction, storage and packaging.

In Tunisia, some oil producers caution that the nation’s traditional methods are of value.

“This is a blessing,” said Zena Ely-Séide Rabia, a 34-year-old boutique oil producer. For instance, she said, picking olives by hand is good for the fruit whereas machines can bruise olives.

Another advantage of Tunisia’s traditional methods is that there is very little use of pesticides or herbicides, making the country well known for its organic oil, she said.

“In 30, 40 years time I would be quite sad frankly if we ended up with an industrialized production style,” she said.

The olive harvest is an integral part of rural life. “They work from place to place,” Ely-Séide Rabia said of olive workers. “It is the fabric of the rural communities. Their lives revolve around these productions.”

Photo: Cain Burdeau for Olive Oil Times

Thus, Tunisia needs to both modernize but also maintain its traditions. “It’s a delicate balance.”

And it is far from clear how quickly Tunisia will want to change or can. “It’s a family production, it’s not industrial like Spain,” said Mseddi Moncef, a 70-year-old olive farmer from Sfax who has about 400 trees.

Many olive orchards are like his: small, family-run operations unlikely to change quickly. And there is resistance to the idea of focusing efforts on producing more oil for exports.

An oil vendor in the Marché Central in Tunis shook his head at the suggestion that Tunisia should take more steps to improve its oil for export markets.

“Exporting is not so good for us. It’s good for the rich,” Adel Ben Ali said. He sells oil in one-liter plastic bottles.

He tasted some of the oil he sells from an aluminum container. It was a fine oil, he said: “It’s natural like this. How can we make it better? More refined?” He shook his head. “No. It’s good like this.”