California Farmer Learns to Adapt to Constant Change

The 2020 olive harvest in California has been significantly impacted by wildfires, plummeting demand due to the pandemic, and power shutdowns. Despite these challenges, Geoff Peters of Showa Farm has managed to donate 40 percent of his 2019 harvest to local food banks while continuing to produce award-winning olive oil. Peters is optimistic about the future and plans to enter his oils in the 2021 NYIOOC competition.

The 2020 olive harvest has been like no other for producers around the world, with climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic creating new challenges for harvesting olives and selling olive oil.

Perhaps nowhere has the impact been more profound than in California. Farmers in the Golden State have had a particularly tough year.

It seemed that it was better, while the oil was relatively fresh, that it went to families that needed it.

Record-setting wildfires raged throughout the state, wiping out everything in their paths. More recently, California has seen a surge in Covid-19 cases and is now reporting the highest daily number of infections per capita in the world’s worst-affected country.

While the pandemic has had a relatively small impact on the olive harvest, demand for the state’s olive oil plummeted, with the closure of much of the restaurant and hospitality sector.

“The high-end market pretty much closed down as people went into shelter-in-place,” Geoff Peters, the owner of Showa Farm, told Olive Oil Times. “That affected us.”

See Also:Producer Profiles“The other thing that affected us was restaurants,” Peters added. “Last October, I had pre-sold 75 to 80 percent of my harvest to some Michelin-star restaurants in New York and we had agreed on everything. I was working out the details of shipping when Covid-19 hit and all the orders were canceled.”

Peters was soon facing a glut of leftover olive oil from the previous year, with the 2020 harvest about to begin. However, the semi-retired marketing consultant decided there was a way to solve his problem while helping out the local community in northern Sonoma County’s Alexander Valley.

“We knew what was going on in the community because of Covid-19, and people were donating to the food banks back in July, long before we even harvested,” he said. “We did not know how long the pandemic was going to last, so when we harvested, we held onto the oil thinking that maybe it would end and we could move on with life.”

“Once it became clear what was going on, what the time sequence was, and I was coming up on the harvest [in October], it seemed that it was better, while the oil was relatively fresh, that it went to families that needed it,” he added.

Nighttime harvesting at Showa Farm

Overall, Peters donated 40 percent of his 2019 harvest to local food banks, upon which California’s farm workers have increasingly come to rely.

The combination of wildfires, which wreaked havoc with the state’s lucrative wine industry, and plummeting demand for a range of agricultural goods from the restaurant and hospitality sectors meant plenty of farmworkers could not find work.

For Peters, who has been growing Arbequina trees on his farm for the past seven years, the growing threat of wildfires presents one of the biggest challenges.

“We’ve had five years of wildfires. Each year they say this is the worst it has ever been, and then the next year is worse,” Peters said. “In northern California when there are wildfires or red-flag warnings about wildfires, the electrical system does what is called a public safety power shutdown.”

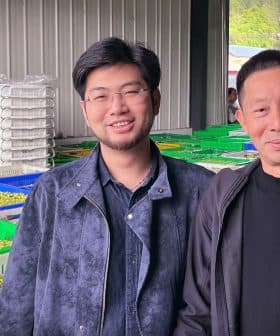

Grandchildren help out on the harvest at Showa Farm.

“What happens is a lot of the mills do not have generators. So, as a result, you can’t harvest because you can’t get your mill to process your fruit within five to six hours of being harvested and certainly not within 24 hours of being harvested if the mill has no power,” he added.

While the fires have not directly impacted Peters’ harvest or the quality of his olive oils, he has found himself increasingly at the whim of the wildfires.

“You have to literally plan your harvest around wildfires and power shutdowns,” he said. “Last year, I harvested 60 percent of my fruit during a particular week, and then had to wait weeks for the fires to be over and power to come back again at the mill before I could harvest the last 40 percent.”

This year, with the Glass Fire just half-a-dozen miles away, he first made sure that his local olive mill would not be subject to a public safety power shutdown.

Freshly harvested olives head to the mill between public safety power shutdowns.

“If we went through and spent a whole day harvesting and then brought five bins to the mill and the mill suddenly loses power, I’ve just lost all of that fruit,” he said.

Due to the low margins of olive oil production and the relatively high levels of power consumption required for the equipment, industrial-scale generators are not an option for many operators.

“The equipment uses a fair amount of electricity, so you can’t just go out to your Ace hardware and get a generator that’s going to power a mill,” Peters said. “It’s an issue, and our fire seasons have gotten progressively worse, so it becomes more and more of an issue every year.”

“As the old saying goes, farming is a crapshoot,” he added. “You’re worrying about the weather. You’re worrying about insects. You’re worrying about fungus. You’re worried about wildfires and now the virus. There are a lot of things that could go wrong.”

With work evaporating for farm laborers, local food banks are busier than ever in California.

And plenty has gone wrong for Peters over his seven-year farming career, but he has learned from each mistake and slowly built an award-winning brand.

“I made every mistake there was in the book at the beginning,” he said, with a wry smile and a bit of a chuckle. “I’ll never forget, before we even planted trees, we had 20 acres (eight hectares) of meadowland, and I went out on a very hot day on my brand new tractor in shorts and a t‑shirt and mowed.”

“I came down with poison oak from head to toe and the other farmers all said ‘why didn’t you wear a Tyvek suit?’,” Peters added. “I said, ‘I thought that was only for people spraying chemicals and I’m organic, so I’m not going to do that.’ They responded ‘no it’s so you don’t get covered in poison oak’.”

That was the first – and most painful – of the many lessons that Peters would learn over the years.

Every year is a different season, different weather, different crop, different things happen. But you also have some things you can control so you try to control those things to improve the quality.

“I didn’t grow up on a farm and had never farmed in my life,” he said. “I went to learn at the UC Davis Olive Center. I had to learn about growing olives and then learn about milling olives.”

“Fortunately UC Davis took me in and I met a lot of interesting people,” Peters added. “Farming is mostly about knowing your other farmers and networking.”

Networking was one of the few skills – in terms of olive growing and oil production – that Peters had prior to planting his first Arbequina trees. Originally, farming had never been in his plans as he began to eye retirement after a long career working in marketing for nonprofits.

“When my wife retired from the federal government in Washington, D.C., she said that we are moving to California and living near San Francisco, so I can be near the grandchildren,” he recalled. “I had no intention of living in California, but it was announced that that was what the plan was.”

See Also:California Yield Will Be Lower than Predicted“I did not want to live in the city anymore, having gone through 90-minute commutes each way each day,” he added. I wanted to be somewhere where I didn’t have to commute anywhere.”

With this compromise on the table, the pair found a property on bare land about two hours north of San Francisco and started to build.

“We had to build a road into it. We had to build well water, septic, build a house, put electricity to it,” he said. “And eventually after we had a roof over our head, she allowed me to plant olive trees.”

The idea for olive trees had long been sitting in the back of Peters’ mind. Prior to his semi-retirement, he used to teach a class about fundraising at the University of Bologna over the summers.

Since he was already there, Peters used this obligation as an excuse to explore Tuscany, where he fell in love with the food, wine and extra virgin olive oil, and specifically monovarietal Arbequina oils.

“We taste tested olive oil all around the world,” Peters said. “We constantly taste tested monovarietals, but tested blends too. Basically, we were trying to determine what type of tree we wanted.”

Once Peters decided on Arbequina, he started to purchase the trees at a quick pace, at one point buying all of the available ones from his local nursery. Currently, he has 800 trees on his farm, all of which, with the exception of some pollinators, are Arbequina.

In 2018, Peters harvested his olives for the first time, producing a modest amount of oil. The following year, he had his first commercial harvest and on the advice of a consultant, started to enter competitions.

Kids and children on the farm for the harvest.

“He tasted my olive oil and said you need to enter this in some competitions,” Peters said. “He said you probably won’t win anything, but at least you’ll get tasting notes back and learn about what you need to do differently.”

So Peters entered his monovarietal Arbequina at the 2019 NYIOOC World Olive Oil Competition and, to his surprise, won a Gold Award. He followed that with a Silver at the 2020 edition of the competition.

This year, Peters has produced and bottled 560 liters of olive oil, a 10-percent better yield than the year before. Based on the feedback he received from judges, he has made a few adjustments, including cutting off his irrigation a week earlier than the previous year in order to intensify the flavor of his oils.

“In many ways, it’s like a trial and error process,” he said. “You learn from what you did right, but you also learn from what you did wrong and you try new things.”

“Every year is a different season, different weather, different crop, different things happen,” he added. “But you also have some things you can control so you try to control those things to improve the quality.”

In spite of all the challenges thrown at Peters by 2020, he is looking forward to the 2021 NYIOOC and already plans to send in his oils.

“When the new bottles come back, I am shipping some to New York and we are going to see whether we learned something to make our oil better,” he said.